From the Chicago Reader (February 17, 1995). — J.R.

One of the strangest things about the elusive career of Otto Preminger (1905-1986) is that it remains elusive not because of the man’s invisibility but because of his relative omnipresence in the public eye. Though never as familiar as Alfred Hitchcock, he cut an imposing figure in the media, registering much more than either John Ford or Howard Hawks. Preminger was well known for his Nazi roles in Margin for Error (1943) and Stalag 17 (1953), for appearing in TV guest spots on Batman and Laugh-In and numerous talk shows, as a colorful player in Tom Wolfe’s Radical Chic, and for grabbing headlines as the man who defied the Production Code of the 50s and the lingering Hollywood blacklist of the 60s while grandly mounting well-publicized movie versions of best-sellers like Anatomy of a Murder, Exodus, Advise and Consent, and The Cardinal. Since he was one of the first of the high-profile American independents after the heyday of Griffith and Chaplin and moved from Hollywood to New York in the early 50s and never shifted his home base later, in most people’s minds he was more producer than director. Nine years after his death, however, it seems that his high visibility — like that of Hitchcock and Orson Welles — served more as mask or camouflage than as any genuine indication of what his movies were about.

With The Moon Is Blue (1953) last weekend, the Music Box began an ongoing series devoted to Preminger’s early years as an independent, beginning with four of the eight movies he produced and directed between 1953 and 1957, all in new 35-millimeter prints. Saint Joan (1957), Jean Seberg’s debut feature, adapted by Graham Greene from George Bernard Shaw’s play, is showing this weekend. The Man With the Golden Arm (1955) follows on February 25 and 26, and Carmen Jones (1954) on March 4, 5, 11, and 12. Later this spring we can look forward to more Preminger pictures, also in new 35-millimeter prints, including two of my favorites — Bonjour Tristesse (on March 18 and 19) and Anatomy of a Murder (March 25 and 26) — as well as the impressive if uneven Advise and Consent (April 1 and 2). The series offers a rare opportunity to reassess a major, frequently misunderstood American director, an artist who was a bewildering mass of contradictions and ambiguities — a prurient but open-minded humanist whose camera was a probing instrument of lyrical analysis. Preminger placed his characters on trial without ever handing down any final verdicts, following them down the diverse garden paths of their wayward natures to see what he might discover; he was a connoisseur of human mystery whose long takes and camera movements were vehicles for pursuit.

The son of a public prosecutor and attorney general of the Austrian empire, Preminger grew up watching trials — and briefly became a lawyer himself after acting in several Max Reinhardt productions and directing a few plays. It’s hardly surprising that he saw most dramatic situations in terms of legal proceedings, in which truths tend to be relative rather than absolute. (Trials play important roles in many of his best pictures, including Angel Face, The Court Martial of Billy Mitchell, Saint Joan, and Anatomy of a Murder.)

Like Erich von Stroheim, Preminger was born a Viennese Jew — but 20 years later and into a much higher economic bracket — and wound up playing the part of a Prussian sadist both on-screen and off. Stroheim, who kept his ethnic roots hidden, was more likely to vent his spleen at producers than at actors or assistants; but Preminger, who became his own producer, was the classic abusive dictator on his own sets. Anatomy of a Filmmaker — an interesting feature-length documentary about his career produced by his own family, hosted by Burgess Meredith, and recently released on video — devotes much of its space to exploring this issue. “I give ulcers, I don’t have them,” Preminger once told Peter Bogdanovich. I can vouch for the accuracy of this remark, having once spent a morning in the mid-70s watching Preminger shoot part of his penultimate feature, Rosebud, in Paris. However gracious he might have been to visiting journalists, he was hell on wheels to some of his employees.

Yet his films, for all their cynical and mordant undertones, are nearly always searching inquiries, almost never imposing foregone conclusions. Apparently the major source of his quarrels with actors was his refusal to give them motivations for their characters, an approach that often plays havoc with dramatic resolutions. But he preferred to keep alive the mystery of his characters’ personalities, to forestall any pat conclusions about them.

The first significant stretch of Preminger’s career was 1944 to 1952 — from Laura to Angel Face, with four other wonderful noirs in between (Fallen Angel, Whirlpool, Where the Sidewalk Ends, and The Thirteenth Letter). The second was roughly the first decade of his independence. There are interesting connections between these two periods — Bonjour Tristesse can be seen as a remake of Angel Face (my favorite Preminger noir), and Anatomy of a Murder, probably his best film altogether, refines some of the virtues of Laura. But the differences between Preminger as a contract director (mainly at Fox) and as an independent are equally striking. Liberated from the noirs and the (mainly Lubitsch-style) costume pictures of his stint at Fox, he gravitated more and more toward all-star blockbuster adaptations of best-sellers that became increasingly bloated. At their best they were grand and thoughtful entertainments; at their worst, the ambiguity typical of Preminger gave way to a sort of demographic calculation that bordered on Hollywood doublethink.

Sometime around the mid-60s, Preminger began to lose his rapport with the public, and he never fully regained it. Sadly, he suffered a major legal defeat around the same time that reversed his fortunes as a pioneering independent: after winning his battles with the Production Code over “risqué” language in The Moon Is Blue and the taboo subject of heroin addiction in The Man With the Golden Arm, he tried unsuccessfully to sue Columbia Pictures and its TV subsidiary, Screen Gems, for granting him no control over the cuts and commercial interruptions made in TV showings of Anatomy of a Murder. (If he’d won, and thereby set a legal precedent, the last 30 years of American film history would have been markedly different.)

By the mid-60s his films had become even more personal, but the garish side of his earlier work tended to take over, with fascinating but often alienating results. The grotesque liberal pieties of Hurry Sundown and Tell Me That You Love Me, Junie Moon and the ugly extravagances of Skidoo (his hippie musical) and Such Good Friends were certainly distinctive and expressive, making these films prime cult material. But the general audience mainly stayed away, leaving it to hard-core enthusiasts (including me) to enthuse over such factoids as that Jackie Gleason’s LSD experience in Skidoo closely approximated Preminger’s own acid trip, for which Andy Warhol served as guide. [2011 afterword: This factoid, which I most likely encountered in the underground press during this period, apparently isn’t true; from more reliable sources, it appears that Timothy Leary was Preminger’s initial guide, although he chose to spend the latter part of his trip alone.] Then Rosebud, probably the nadir of his career, discouraged even us fans; and the touching sincerity of The Human Factor, his last film, which he financed with great difficulty, counted for virtually nothing.

A favorite among auteurists, Preminger has never registered as a meaningful stylist with the general public, even when his movies were popular, largely because he never stuck to the same kinds of pictures and always discussed social issues in his interviews rather than style or technique. Pauline Kael argued in 1963 that his very diversity was a flaw: “If Preminger shows stylistic consistency with subject matter as varied as Carmen Jones, Anatomy of a Murder, and Advise and Consent, then by any rational standards he should be attacked rather than elevated.” From the standpoint of conventional aesthetics, Kael has a point. But arguably Preminger, an investigator eager to pry into all sorts of material, changes some of the conventional rules by which we define success and failure, at least if we can join in the spirit of the search.

What remains interesting about The Moon Is Blue is less the frothy romantic-comedy material of F. Hugh Herbert’s play — which ran for 924 performances when Preminger directed it on Broadway — than the peculiar emphasis Preminger brings to it. The most warmly depicted character is neither the architect hero (William Holden) nor the perky “professional virgin” (Maggie MacNamara) he picks up, who register as sour and brittle respectively, but the hero’s next-door neighbor (David Niven) — an aging amoral playboy whose daughter is Holden’s former fiancée. But thanks to Preminger’s detached direction, all three characters emerge as interestingly unpredictable, each revealing aspects that complicate his or her generic role. Preminger clearly likes all of them, which marks him as a humanist; but his interest in the darker sides of the two romantic leads and the brighter facets of the playboy complicate his humanism with a dash of prurience.

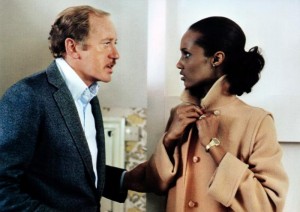

From a conventional standpoint, a good bit of Carmen Jones is not only mannerist but downright monstrous. Recasting Bizet’s opera with contemporary blacks and substituting prizefighting for bullfighting, a parachute factory for a cigarette factory, and a GI for a Spanish corporal might make some sort of sense if a consistent level of reality or fantasy were established. But this is a gaudy fantasy, completely lacking in white characters, filmed in realistic locations. Furthermore, all the lead actors apart from Pearl Bailey (including Dorothy Dandridge and Harry Belafonte) are dubbed by opera singers: in Oscar Hammerstein’s original stage musical, I’m told, the music was scaled down to show-tune registers to accommodate nonopera singers, but Preminger decided to bend the material back in Bizet’s direction, just as he perversely plunked down the fantasy of an all-black world in a naturalistic American environment.

James Baldwin, appalled by the results, recorded his dismay — especially about what the movie revealed about white fantasies of black sexuality — in his first collection of essays. Two decades later, English film theorist V.F. Perkins devoted three pages of enraptured analysis to Preminger’s dynamic ‘Scope framing within a single sequence of Carmen Jones. In a way, these two very different critics are both right, and if one adds to Perkins’s ardor the positive allusions to the film in Godard’s Prénom: Carmen and in the title of an essay by French critic Michel Mourlet, “From Velazquez to Picasso, or From Bizet to Preminger,” it becomes clear that the movie’s extravagant stylization is intoxicating as well as incoherent, a sort of cinematic equivalent to gin mixed with root beer. From the moment that Carmen first appears in her flaming orange red skirt in the parachute factory — the first explosion of bright color in the movie after the browns and olive greens of the opening on a U.S. Army base — Preminger luxuriates in the incongruous world he’s devised as if it were the most natural place on earth. (It’s worth adding that he wasn’t the only one to respond: Carmen Jones was probably the first movie with an all-black cast to score big with the general public.) Preminger’s encounter with that world is so vibrant the movie fairly leaps off the screen, leading us into a brazenly overripe universe of extremes and contrasts in which Bizet’s music and Merimée’s characters actually seem at home.

Because Preminger was never afraid of the kind of excess normally associated with bad taste, practically every movie beginning with The Moon Is Blue teeters on the verge of camp — and some, like Carmen Jones, do more than teeter. (The main exceptions are his brief returns to studio contracts during the 50s — River of No Return, The Court Martial of Billy Mitchell, and Porgy and Bess –and the virtually perfect Anatomy of a Murder.) But along with the excess one finds the sort of drive, flavor, and vitality that “good taste” commonly rules out.

Preminger’s liking for jazz — which bore fruit in the robust big-band scores of Elmer Bernstein for The Man With the Golden Arm and Duke Ellington for Anatomy of a Murder — led him to feature Max Roach in a clumsy cameo in Carmen Jones. This move is emblematic of his desire to fill the screen with a more diversified picture of American life than is found in most Hollywood movies, even if his impulse produces awkward or incongruous moments. It’s as if he wanted to express the democratic ideal literally, by cramming as many people as possible into his frames, and then traced a steady path through the resulting maelstrom with his questioning camera.

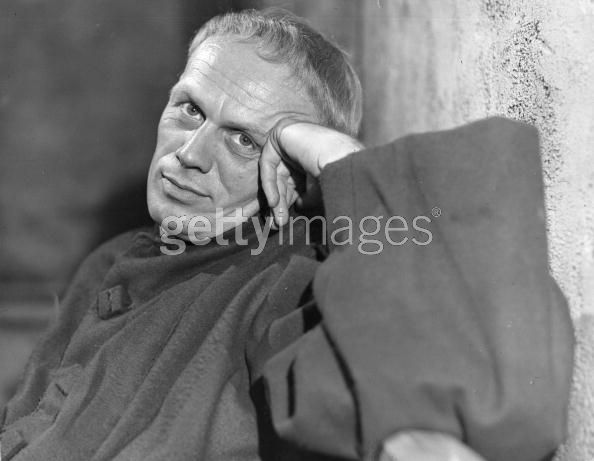

Though Carmen Jones was popular, in 1957 Saint Joan was a critical and commercial disaster. Yet it looks quite reasonable and effective today. Jean Seberg — whom Preminger discovered in a heavily publicized international search for the lead — was slammed by virtually everyone, but it’s hard to see today what the critics were complaining about. Though she was raw and lacked experience, her passionate performance makes her Joan of Arc touching and believable.

Admittedly this is Preminger’s only art film, with an intellectual tone uncharacteristic of his work; and the narrative loses some of its footing when Preminger has to change gears between the witty dialogue of the first part and the later, more tragic period of Joan’s incarceration. But Georges Perinal’s exquisite black-and-white cinematography and the fine deliveries of the Shavian dialogue (by John Gielgud, Anton Walbrook, and Richard Todd among others) keep the movie enjoyable, as does the remarkably adept and uninhibited mugging of Richard Widmark as Charles, the dauphin. In a manner peculiar to Preminger, this is a foppish, decidedly unmacho treatment of the character that suggests at times a goofy Jerry Lewis performance. And against all the odds, it blends beautifully with the material (at least if one isn’t unduly distracted by Widmark’s latex makeup in the opening scene).

Eventually, Widmark’s clownish accompaniment to Joan’s prose arias even helps to clarify Shaw’s kaleidoscopic approach to the issue of Joan’s unwavering faith. Since Shaw was a nonbeliever, one might expect him to undercut her convictions, but by surrounding her with unreligious rakes and never mocking her he makes it clear that the strength of her beliefs matters more than the beliefs themselves. And because Preminger is always interested in the machinations of power, the threatening force of Joan’s purity becomes the central issue, the through line — the precise equivalent of Preminger’s steady camera moving through a crowd. When Preminger has Joan deliver a devout soliloquy in close-up while he frames the dauphin playing hopscotch behind her in deep focus, he distills the political dynamics of this feminist story into a single image.

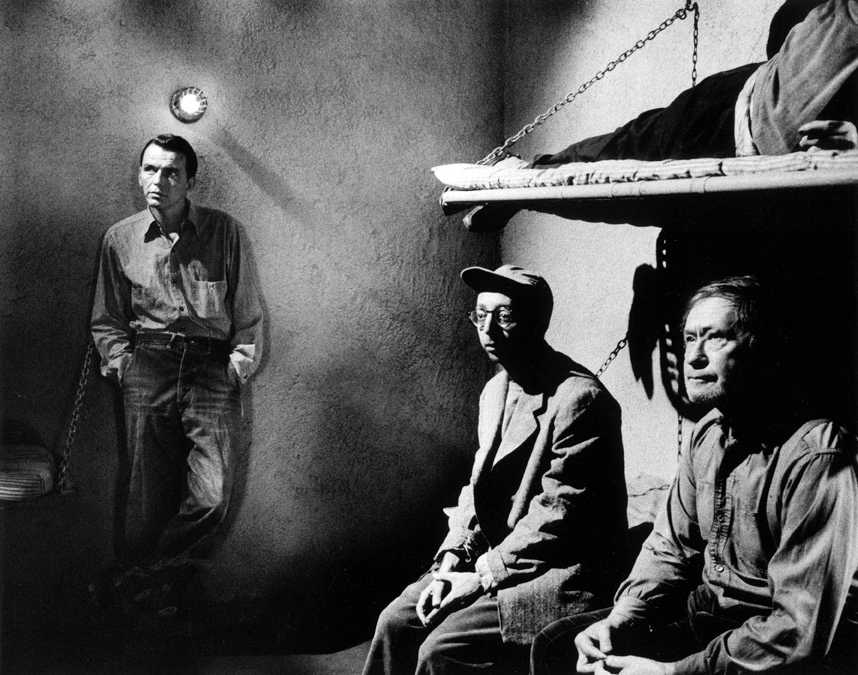

But the most potent movie among the four considered here is undoubtedly The Man With the Golden Arm. It packs the biggest wallop, and it features what is surely the strongest of all Frank Sinatra’s dramatic performances, as well as the most affecting and glowing of Kim Novak’s. (Critic Raymond Durgnat once wrote that in this film “she blends a soft body with a butch suspicion and a childlike potentiality for devotion” — a description that clearly ties her to Seberg, MacNamara, and many other of her weird sisters in the Preminger canon.)

The film’s power has little to do with the Nelson Algren novel on which it’s based. Algren himself conceded that “it was better than most movies” and that he liked the music and Sinatra, but said he was sorry that “it was a Chicago story that had nothing to do with Chicago. Some of the people were dressed like old Vienna and some like old San Francisco. The book very specifically took place at a certain time, at a certain locale, and the movie took place nowhere.” Indeed, as Dave Kehr has aptly noted, the film’s style, including its black-and-white cinematography, is basically expressionist — filmed on sets rather than on location (a rare departure for Preminger) and peopled with grim characters who seem to have emerged from German expressionist nightmares rather than the streets of Chicago. The lighting and atmosphere are noirish, but the blighted human landscape is infernal — despite the relentless social determinism, which one would ordinarily associate with realism, in this tale of a beleaguered poker dealer, former junkie, and aspiring jazz drummer trying to go straight.

Preminger eschews the poetic realism of Algren, but his movie exudes a funky poetry all its own. Similarly, his depiction of heroin addiction may be flawed in certain details, but as a portrait of addiction pure and simple and the cruel power plays it sets in motion, it’s indelible, and as black as the darkest night. In the furtive anguish of this doom-ridden universe riddled with sordid streets and single-room flats, every interior is either a shelter or a prison, and every individual has the mysterious capacity to make it turn from one to the other at the drop of a hat. If Preminger knows what grants his characters that power, he isn’t saying.