From the Chicago Reader (September 14, 2007). –J.R.

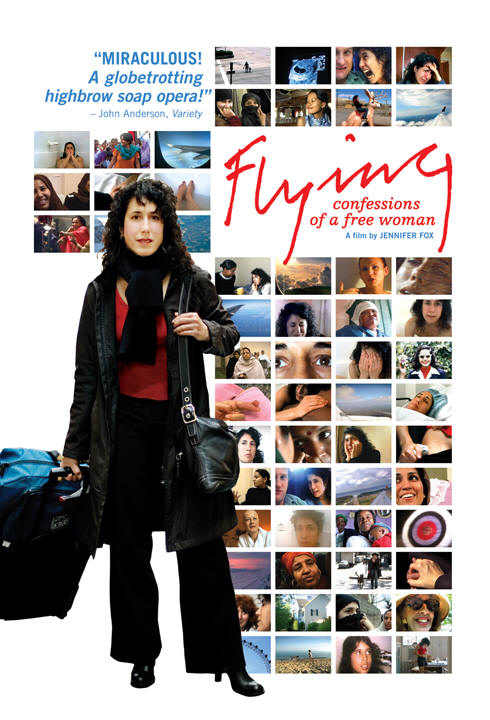

FLYING: CONFESSIONS OF A FREE WOMAN ***

DIRECTED AND WRITTEN BY JENNIFER FOX

There’s something nervy about the way Jennifer Fox, in her new autobiographical six-part, six-hour miniseries, showing this week at the Gene Siskel Film Center, tries to combine her life, her art, and her politics. Made with funding from the Danish Film Institute over a four-year period ending in late 2006, Flying: Confessions of a Free Woman recounts the privileges, confusions, and self-examinations of Fox, a Manhattan-based filmmaker in her mid-40s who grew up associating her freedom with being like a boy, feeling much closer to her permissive father than to her disapproving mother, and never having the slightest interest in getting married or (until recently) having kids.

Known for such PBS documentaries as Beirut: The Last Home Movie (1987) and An American Love Story (1999), a miniseries about the everyday life of an interracial couple, Fox does a fair amount of globe-trotting, and during the time frame of Flying she’s juggling two lovers on separate continents who know about each other. The less serious relationship is with Patrick, a Swiss-German cinematographer she sees more often, mainly in New York (he’s credited as the film’s “technical supervisor”). Kye is a South African poet she sees infrequently in South Africa, where she sometimes teaches. (Kye’s married with kids and keeping his affair a secret; he remains almost completely off-camera.)

More than a simple diary film, Flying is also a kind of essay about what freedom for a contemporary woman consists of. On her travels and in New York, Fox records many conversations she has with other women about this topic. The women vary in age, nationality, ethnicity, and class and include Fox’s ancient grandmother, a 54-year-old Somalian exile in London fighting to end female genital mutilation, a married 43-year-old Egyptian journalist in France who combines work and parenting, a 32-year-old Pakistani villager and activist who’s chosen not to marry, and a 22-year-old single mother in Soweto sharing a house with her unemployed relatives.

Fox’s immediate personal issues provide most of the connecting threads of the series, with many unexpected plot turns along the way. But her connection with so many women points to the transition she makes from identifying with men to identifying with women, even while recognizing that sometimes women, herself included, can unwittingly collude in their own oppression.

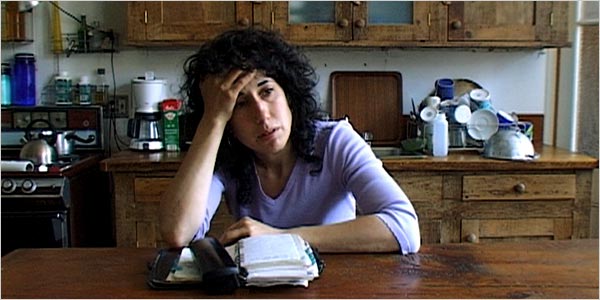

There were times when I wished Fox had more of a sense of humor about herself and her project, if only because her poker-faced seriousness gets monotonous. But the most problematic part of the enterprise is that she has to fictionalize certain aspects of her life to create an easy-to-follow narrative. That is, she has to give her material — and therefore the representation of her life — a coherent shape without calling too much attention to the process. Camera placement and editing are essential tools in this endeavor, but it works against her purposes for the audience to think about them too much.

A simple, prosaic example of what I mean is the occasional unacknowledged presence of another camera operator. Fox records most of her dialogues by passing the camera back and forth with her interlocutor, allowing us to view both sides of the exchanges. And there are other times, such as when she’s seen riding on a plane alone, when we presume that’s she managed to position her own small camera without assistance. But there are some sequences that encourage us to conclude that she’s alone when she couldn’t possibly be — such as when we see her pensively walking her dog in Manhattan. I guess we’re supposed to ignore the trickery and concentrate on more important matters, but I found it distracting, and even after I adjusted, the artificiality undermined the authenticity of what I was watching.

The problem is, when you’re doing so many different things at once — struggling with your values, filming your struggle, and trying to make it compelling while remaining honest — something ultimately has to give. No one’s life qualifies as an absorbing soap opera all the time, and clearly special solutions are required for those junctures when it doesn’t. So it’s the moments when the narrative of her life appears to be most artfully arranged and told that Fox’s undertaking starts to seem most questionable. (Her elliptical ways of representing Kye–showing just enough of him, or of a stand-in, to reveal that he’s black, but without making a big deal of the fact that theirs is an interracial romance — create some related ambiguities.)

She’s pretty fearless about revealing her own self-absorption and allowing herself to be irritating. She also raises the question of whether the project is actually affecting her life and her decisions about it — not just upping the ante but goading her into a kind of ongoing self-definition. It’s certainly having an effect on some of the others we see. Patrick in particular, who seems unusually accepting about many aspects of her life, adamantly refuses to be filmed at times — and considering that he’s collaborating on the filmmaking more than the dialogue seems to acknowledge, we start to realize that his decisions about her film automatically become decisions about his life and her life as well. Our not being allowed access to certain parts of the filmmaking process — especially the editing, which is obviously a central stage — eventually suggests that what we’re really watching is more a construction than a discovery, of a life as well as a film.