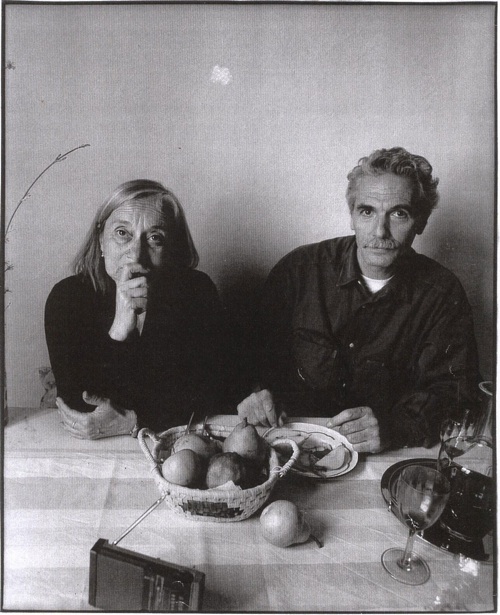

From The Soho News (July 2, 1980). This was my first encounter with the delightful and inspired couple Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi, subsequently known for their wonderful found-footage films, e.g. From the Pole to the Equator (1987) and Prisoners of War (1995). — J.R.

One interesting thing about aesthetic hybrids — movies with smells, or jazz posing as film criticism — is that nobody knows what to do with them, critics included. Whether these unusual and unlikely yokings represent examples of useful, exploratory or merely wishful thinking is essentially a matter of personal taste. In the two instances under review, a crucial factor in determining one’s taste is packaging, pure and simple — how and where an audience gets placed.

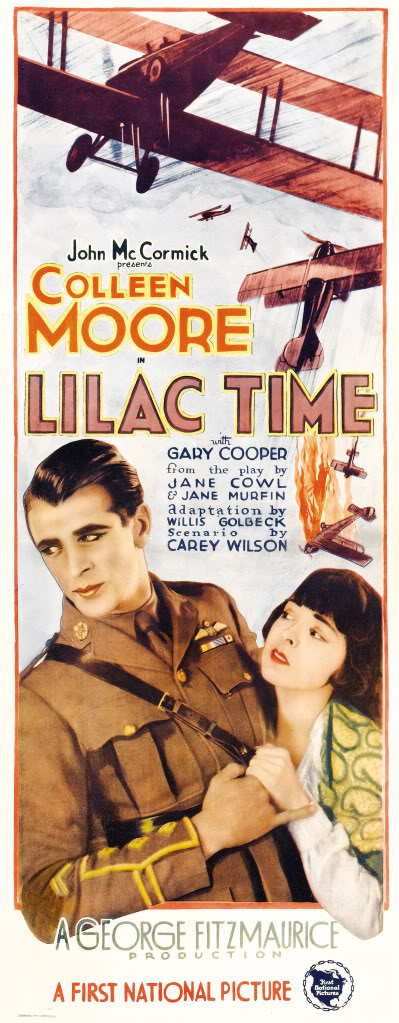

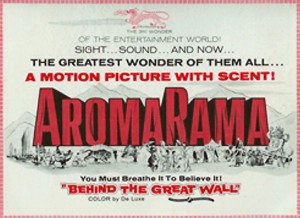

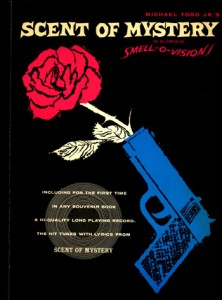

Apart from isolated experiments — including a recent one by Les Blank, reportedly utilizing the odors of red beans and rice — it seems that commercial efforts to link smells with movies have mainly come in two separate, pungent waves. A couple of early talkies, Lilac Time and The Hollywood Revue, played around with the idea in a few theaters; the latter, a plotless musical, climaxed with a snoutful of orange scent to go with “Orange Blossom Time,” performed by Charles King and the Albertina Rasch ballet company. Then, 30 years later, the competing arsenals of Aroma-Rama and Smell-O-Vision quickly drifted through a few big cities, accompanying a documentary (Behind The Great Wall) and thriller (Scent of Mystery) respectively. The former, developed by Charles Weiss, filtered its smells through the theater’s air-conditioning system; the latter, pushed by Mike Todd Jr., projected its own odors through tubes to every seat in the house.

One thing that immediately distinguishes the Olfactory Cinema recently presented at Anthology Film Archives from the various attempts at “smellies” listed above is the absence of any illusionist ambition. (The smells — most of them reminiscent of incense flavors – are meant to counterpoint the connotations and evocations of the images rather than simply bolster them.) The technology of Olfactory Cinema is certainly more austere and artisanal — in keeping with the rather homemade silent, super-8mm images — and even somewhat alchemical in appearance. The filmmakers, a couple from Milan, sit in the front row with 14 open metal containers in front of them, each one heated by an alcohol flame and fed by eyedroppers with diverse perfumes. (The latter are produced by the father of Yervant Gianikian, one of the filmmakers.) Actually, the hissing and sizzling noises that result have a much more direct sensual impact than the subtle succession of tangs in various overlapping mixtures – even to a nosmoker like me who’s sitting a row or two away.

To be blunt about it, most of the show baffles me, sight and smells alike. The three films included, all of which are principally composed in pixilated stop-motion, are centered around duplicating toys, the Lambroso Museum in Turin (named after a physician who studied the olfactory sensitivity of criminals), and fragments of found 9.5 mm footage (from silent films including Dupont’s Variety, Fanck’s The Holy Mountain, L’Herbier’s L’Argent and Willcoff’s Casanova.) Filmmakers Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi dutifully squirt out smells through all three. It isn’t clear how much (or how often) their activity is improvised, but linkages of image and smells are necessarily somewhat loose and haphazard – determined as much by the spectator’s inhaling and exhaling patterns as by the filmmakers’ squirting and editing patterns.

From the little I could gather from Gianikian’s limited English afterward, it appears that he and Lucchi are involved in a quasi-Proustian experiment with psychological responses to odors. (According to Janis Crystal Lipzin, they have composed a catalogue of over 800 essences.) Unfortunately. all this sounds a lot more interesting than it either looks or smells — at least without an adequate understanding of how much of the strategies of the filmmakers are scientifically and/or aesthetically motivated in any consistent way. Which is another way of saying that I need a more definable place in relation to their crossbreeding, a place that words might have provided.

***

No such verbal deficiency is apparent in relation to pianist-composer Ran Blake’s new album, Film Noir –- a much more slickly packaged and accessible cultural item. With introductory notes by no less than Andrew Sarris on the back of the jacket, as well as a few guidelines from Blake himself -– head of the Third Stream Department at the New England Conservatory -– this venture certainly gives one a sporting chance to place oneself imaginatively in relation to the music.

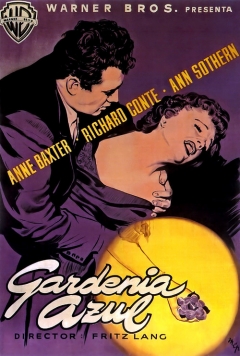

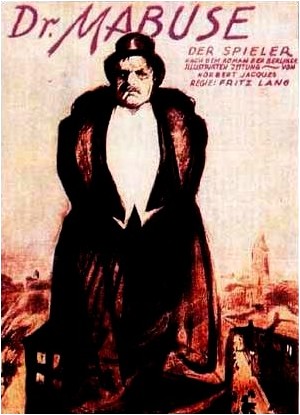

Ranging from solo piano (on “Eve” and “Le Boucher”). diverse duos (with Ted Curson’s trumpet on “Garden of Delights.” George Schuller’s drums on “Doctor Mabuse” and Daryl Lowery’s alto sax on “BIue Gardenia”). a trio for “Key Largo” and three separate quartets (for “Spiral Staircase,” “Pinky” and “Streetcar Named Desire”) to the big band assembled for “Touch of Evil” and “The Pawnbroker” (the latter arranged by Lowery). Blake’s hybrid doesn’t adopt any fixed approach to deal with its cinematic material but relates to film noir in a number of different ways. (Without the album’s title and notes, its relations to film noir probably wouldn’t be apparent.)

Sometimes the idea is to embellish a thematic idea from the original soundtrack score: Roy Webb’s in The Spiral Staircase, Alfred Newman’s in All About Eve and Pinky, Alex North’s in A Streetcar Named Desire, Quincy Jones’ in The Pawnbroker, and songwriters Russell and Lee in The Blue Gardenia. Otherwise, Blake’s points of departure are certain thematic and/or formal impressions made on him by the films themselves – except for the case of “Key Largo,” which is based on Benny Carter’s impressions of Key Largo and its title tune. “Often when I play,” Blake says in a press handout, “I’ll forget the audience and imagine a screen in front of me with pictures, and a lot of that is very vivid. . .films and images do flash in front of my eyes when I play.”

The old-fashioned term for this concept is program music, which raises the question of how much the film noir idea might be a marketing gambit –and one that incidentally manages to corral at least three not very noirish movies (All About Eve, Pinky, and A Streetcar Named Desire) into its stable.(The Pawnbroker is borderline and I’m not counting Garden of Delight, a film that, as far as I’ve been able to ascertain from reference books, exists only in Blake’s head – unless he’s thinking of Spanish director Carlos Saura’s 1969 El Jardin de las Delicias.

In other respects as well, Film Noir relates to its title in ways that are playful and loosely evocative rather than rigorous. One should listen here for neither the interpretive brilliance of André Hodeir’s Anna Livia Plurabelle album on Epic (EPC 64695) — which enhances James Joyce’s text from Finnegans Wake musically even when its French vocalists betray it by mispronouncing some of the puns (musical logic thereby superceding literary logic) nor the subtlety/obscurity of Blake’s stated musical models (Ives, Webern, Monk) when, for instance, he tries to get at A Streetcar Named Desire by contriving to create percussive equivalents to a choo-choo train.

He’s at his most mysterious and phenomenological when he informs us in his notes that the “last section of ‘Pinky’ depicts an incident that occurred in a Springfield, Mass., theater when I saw the film,” without breathing a clue about what that incident was. In this case. I wouldn’t say that the results swing, but neither does the Elia Kazan movie.

I haven’t seen The Spiral Staircase, but according to Sarris’ suggestive notes, “Blake seems to have musically apprehended the two polarities of the plot, the first from the fearful but innocent point of view of Dorothy McGuire’s memorably mute serving girl facing an unknown madness in an old house, and the second from the point of view of the voyeuristic madman himself as he prepares to wreak his havoc. ”

“Touch of Evil,” my favorite track, evokes the seedy Orson Welles classic in a number of interesting ways, from the use of demonic brass to suggest Mexican border traffic to the touch of Afro-Cuban rhythm (which recalls Henry Mancini’s soundtrack score without duplicating any of it) to some a cappella vamps that seem to delineate the neon sign that punctuates Welles’ strangling of Akim Tamiroff in a dumpy hotel room.

More generally, the film is brought back through a nightmarish obsessiveness that interestingly brings to mind another South-of-the-border “melodrama” put together the same year (1957): Charles Mingus’ memorable Tijuana Moods album. Some of Mingus’ old Jelly Roll Morton lampoons are evoked as well in the “Blue Gardenia,” the closing track –- which, incidentally, continues a Fritz Lang theme stated in the preceding “Doctor Mabuse,” thereby qualifying as Sarris-inspired auteur criticism in the bargain. Thanks to words and a few other packaging tools, a fair-to-middling jazz album thus becomes a clean, noirish blackboard on which we can chalk our own vibrant fantasies.