From the Chicago Reader (May 13, 2005). — J.R.

Crash

*** (A must see)

Directed by Paul Haggis

Written by Haggis and Bobby Moresco

With Don Cheadle, Sandra Bullock, Matt Dillon, Jennifer Esposito, William Fichtner, Brendan Fraser, Terrence Dashon Howard, Chris “Ludacris” Bridges, Thandie Newton, Ryan Phillippe, Larenz Tate, Nona Gaye, and Michael Pena

Mindhunters

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Renny Harlin

Written by Wayne Kramer and Kevin Brodbin

With Eion Bailey, Clifton Collins Jr., Will Kemp, Val Kilmer, Jonny Lee Miller, Kathryn Morris, Christian Slater, LL Cool J, Patricia Velasquez, and Cassandra Bell

Monster-in-Law

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Robert Luketic

Written by Anya Kochoff and Richard LaGravenese

With Jane Fonda, Jennifer Lopez, Michael Vartan, and Wanda Sykes

We tend to make trade-offs between reality and fantasy when we watch movies, buying into some questionable premises because we want to honor others. Despite shared assumptions and conventions, we have different thresholds for what we find believable — or an acceptable version of what’s real. We’ll settle for a certain amount of contrivance, but our tolerance has limits, determined in part by age, taste, and experience and in part by whether we like the rest of the movie enough to stretch our standards.

A case in point is Crash, the directorial debut of Paul Haggis, the screenwriter of Million Dollar Baby. It’s been garnering praise for its honesty about how much racism and xenophobia affect everyday urban existence. I’ve seldom seen so many racial and ethnic slurs hurled about by so many characters, heroes and villains alike (though Jan Hrebejk’s Up and Down, a strikingly similar feature from the Czech Republic that was recently nominated for an Oscar, comes close). Because this kind of discourse is routinely screened out of movies, we’re likely to accept the profusion of insults as unusually candid or real, particularly given the spirited and talented ensemble cast, which Haggis directs with sensitivity.

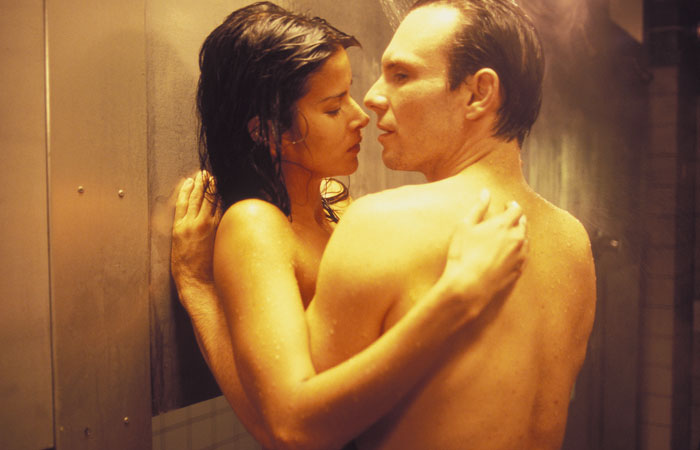

Following the template of films such as Short Cuts and Magnolia, Crash tells several independent stories that gradually merge. But it’s blatantly contrived, depending on coincidence and surprise for much of its interest, and it’s hard to believe that so many characters from different walks of life could cross each other’s lives in so many different ways in a single day. To cite only one example — which includes a spoiler — how likely is it that the racist white cop (Matt Dillon) who gropes a well-to-do black woman (Thandie Newton) while pretending to search her for weapons one night will be the officer who rescues her from a potentially fatal car accident less than 24 hours later, or that during the same time frame his partner will save her husband from being shot by another policeman?

I saw the film a second time largely to determine whether the transparency of such plotting undermined the larger social message. I decided that it didn’t, because I valued the truth of that message — that, for instance, a racist cop is perfectly capable of saving a black person’s life — over the falsity of the plotting, and because I decided that this falsity was intended to articulate other truths. Haggis wants to implicate us as well as many of his more sympathetic characters in the round-robin of prejudice, so he plays tricks with our expectations, making us retroactively aware of our own prejudices — not unlike the surprise endings of O. Henry. That we can feel pleasure when these twists are revealed sometimes mitigates the deceptions that make them possible. And sometimes it doesn’t.

The way we determine what’s true or false, real or artificial, good or bad in movies tends to be highly individual. As a reviewer, I’m obliged to give movies star ratings, but they’re simply a summary of my personal response, not a declaration of some objective value and certainly not of any sort of consensus. I was taken aback recently when I received a couple of e-mails from Star Wars fans asking how I could have concluded eight years ago that the “special edition” rerelease of that film was “worthless” when it gave so much pleasure to so many people. I might have given it an even lower rating if I could have, but all I meant by giving it no stars was that it was worthless to me. I’m not qualified to speak about its value to anyone else.

In my reviews I try to describe the paths that lead to my subjective response so that readers can decide whether some part of my path might be theirs too. In the case of Crash I may blanch at Haggis’s narrative contrivances and think two stars, though I did enjoy them (three stars). But the vision of Los Angeles that they’re designed to express strikes me as just and vital (four stars). So I wind up with an average of three. Viewers who find the vision uninteresting and the narrative contrivances acceptable but unenjoyable will come up with ratings of their own — or arrive at the same rating for entirely different reasons.

Following the same process, I think Mindhunters has the dumbest whodunit thriller plot and the least plausible moves of any film I can think of (no stars): FBI trainees are sent by a stern instructor to a remote island to test their reflexes and sleuthing powers when putting together psychological profiles, but then each of them in turn gets baroquely bumped off. Yet parts of this idea are competently cribbed from Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None, a mystery novel I loved as a kid (three stars). The movie is filled with gross-out violence and gore (no stars), though it did give me plenty of jolts and surprises (three stars). It’s directed with gusto by Renny Harlin, who certainly knows how to make an action flick better than most (four stars), though I don’t much care for action flicks (one star). I missed Harlin’s widely scorned previous effort, Exorcist: The Beginning. But according to William Peter Blatty, author of the original’s source novel, this costly reshoot of Paul Schrader’s Dominion: Prequel to the Exorcist should be credited more to Morgan Creek, the film’s production company, than to the director, so I have to factor in such judgments as well. All this averages out to just under two stars.

Watching Monster-in-Law, I admire the gutsiness of Jane Fonda playing an unsympathetic character who’s her own age and looks it (three stars) — a hysterical, self-centered former TV celebrity who’s horrified that her son’s marrying a temp and tries to make the woman so miserable she’ll flee before the wedding. But I’m appalled by the strident sitcom overkill that surrounds Fonda on every side (no stars) — every other character is a cliche or a nonentity — and by the pat conclusion: a last-minute, deus ex machina cameo by Elaine Stritch inspires Fonda’s character to undergo a complete reversal in time to guarantee a happy ending. The particles of truth clinging to her basically phony character eventually became irrelevant to me.

Her son (Michael Vartan) is a clueless twerp who’s supposed to be a perfect catch even though he can’t see the monstrousness of his mother (no stars). His prospective wife — played by Jennifer Lopez, an actress I immoderately adore (three stars) despite the dumb parts she keeps accepting (no stars) and the excessive press coverage she gets (immaterial) — is a boring simp, even after she starts retaliating with some nasty tricks of her own (one star). And I’m only half-amused (one star) by the mother’s black assistant (Wanda Sykes), who sees through all her boss’s guff and periodically fires back salty one-liners –a part that half a century ago might have been assigned to Joan Blondell (though there are also uncomfortable echoes of Hattie McDaniel). This averages out to a little more than one star, but less than two. I’ll stick with one, since to boost this movie’s rating to “worth seeing” would make me feel like a publicist or simply a dope.