Written for the 2022 catalogue of Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. Because I miscalculated the requested word length, this is much longer than the version that they wound up using.– J.R.

PINK FLAMINGOS

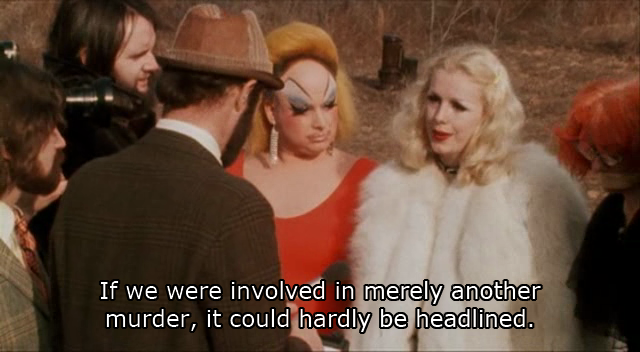

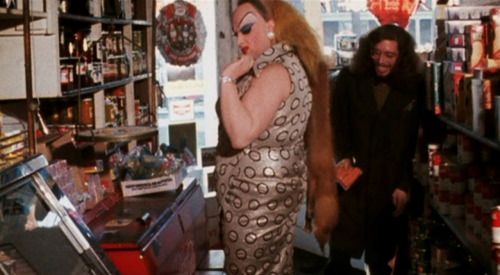

Dare I say it? John Waters may be the closest thing North Americans have to a contemporary successor to Mark Twain, especially if we regard the latter figure more as a multifaceted public entertainer than as an artist (which is indeed how Twain’s contemporary audience generally perceived him)—in other words, most often as a genial host, and not exactly as a poet. This helps to account for why Pink Flamingos, the deliberately sleazy 1972 feature that made Waters famous, owed the greater part of its fame to the fact that it ended with a chubby drag queen named Divine (named after the hero[ine] of Jean Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers, whom most of the star’s fans most likely never read or even heard of) gobbling up dog shit. And because Waters’ gifts as a writer and standup humorist have always tended to surpass and overwhelm his talent as a film director — something that was already apparent in Shock Value: A Tasteful Book About Bad Taste (1981), the first of his many entertaining books–we remember his early films more for their eccentric cast members and their cockeyed premises than for the style of their mise-en-scene. If Waters proudly brandishes the influences of Jean Genet, William Castle, and Little Richard, seemingly incompatible denizens of the criminal underground and the commercial mainstream, respectively, these are mainly for their shared theatrical sensationalism and joyful exhibitionism, not the subtler virtues of Genet as a prose stylist and as the filmmaker of the silent Chant d‘amour, Castle as the director of low-budget noirs such as When Strangers Marry and The Whistler, and Little Richard as the grower or painter of a razor-thin mustache that Waters has recently admitted he consciously copied. Given the calculated excess and hyperbole of Waters’ themes and cast, the amateurish line deliveries and haphazard cinematography are usually perceived not as flaws but as badges of authenticity.

One could say that Waters does have a certain sense of style, particularly when it comes to the exhibitionism and the lapsed Catholicism tied to his sense of rebellion. But he’s none the less mainly appreciated as a purveyor of outrageous content — a gross-out specialist who celebrates scandal for its own sake, and simply as a means of attracting attention. This is surely why and how his early films flourished as midnight movies in the early 1970s. As Jim Hoberman remarked in the 1983 book that we coauthored on that subject, in contrast to the films of David Lynch, “Waters’ films have no quests: they exist in an eternal now, with no progression. They’re vaudeville —except for Female Trouble, which is about Divine’s quest for celebrity and immortality, and paradoxically ends with her death….Pink Flamingos is about a kind of contest, but there’s no progression.” Hoberman went on to maintain that Waters had a major impact on Jack Smith because, as in Flaming Creatures, we’re taken to a particular place for the duration of a film’s running time rather than a narrative with a beginning and end. I would add to this that even though Pink Flamingos ends climactically with Divine eating dog shit, this is very much a vaudeville “closer” rather than any sort of narrative resolution.

The “contest” alluded to by Hoberman is basically what Dave Kehr once described as “a competition between Divine and the Marbles [Mink Stole and David Lochary] — a couple of up-and-coming sleazoids who peddle black-market babies to lesbian couples — for the title of ‘the World’s Filthiest Person’”. Other characters include Divine’s hefty egg-obsessed mother (Edith Massey) and her crazed hippie son (Danny Mills), among other Waters regulars of this period (e.g., Mary Vivian Pearce, Cookie Mueller, Susan Walsh). The movie’s key image, to my own taste, is not Divine eating shit but her parading pridefully and resolutely down the street to the strains of Little Richard hollering “The Girl Can’t Help It”– an obvious tribute to Jayne Mansfield’s strut in Frank Tashlin’s film of the same name.

-–JONATHAN ROSENBAUM