From Scenario, Spring 1999, Vol. 5, No. 1. -– J.R.

The recent video release and cable premiere of Louis Feuillade’s silent French serial Les Vampires (1915- 1916), making it widely available in the United States for the first time in 80-odd years, clarifies the origins of the paranoid thriller in a particularly acute way. All the basic elements that we associate with movie conspiracies are fully present in Les Vampires, at least in some rudimentary form: high-tech surveillance techniques, secret lairs, hidden wall panels, intricately concealed weapons, elaborate disguises, diverse forms of mind and memory control.

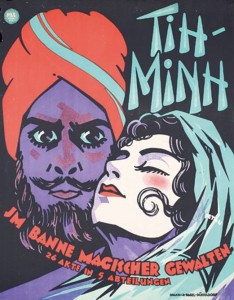

This arsenal of paraphernalia and technology, suggesting that the ordinary world isn’t quite what it appears to be and that everyday life is full of concealed plots and hidden dangers, is surely a staple of this century that didn’t have to wait for video surveillance or the digital revolution before it took over people’s imaginations. Though the political casts of the designated villains fluctuate wildly according to the ideology of the country and period — ranging from the anarchist Vampire gang to the red spies of Cold War thrillers, to the nearly invisible capitalist tycoons of Cutter’s Way (1981), to the smug government bureaucrats in the significantly titled Enemy of the State — the evil designs remain more or less the same. The key villain in an equally great crime serial of Feuillade, Tih Minh (I919), is a German spy named Marx, suggesting that the French fear of Bolshevik and Germans was every bit as operative in the teens as an anxiety about technology.

It was part of the poetic genius of Feuillade to plant these worries in an immediately recognizable workaday world whose reality was generally vouchsafed by a fixed camera in contemporary locations. Mise en scène and relatively long takes were the basis of his aesthetic — unlike the editing of D.W. Griffith around the same time across the Atlantic.

Conspiracies and masterplots weren’t exactly absent from the intrigues of The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916): think of the racial paranoia of the former and the latter’s visual rhyme effects linking strife in modern America with the Crucifixion, the Fall of Babylon , and the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. But these links took on different shapes and emotional meanings, not only because they reflected American ideology of the teens, but also because they were mainly articulated in terms of montage. And it arguably wasn’t until Fritz Lang in 1920s Germany began to fuse the formal discoveries of Feuillade and Griffith that the paranoid thriller as we know it today began to take shape.

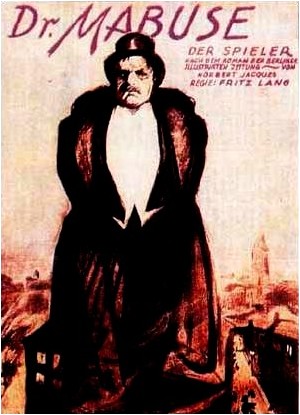

Lang’s Dr. Mabuse, The Gambler (1922) originally opened with a brief, rapid montage depicting recent violent events in German history such as the Spartacus uprising, the murder ofWalter Rathenau, and the Kapp putsch. But even without such a prologue, this two-part thriller whose first part is subtitled A Picture of the Times furnishes all the conspiracy theories one could hope for. It begins, in fact, with an intricate demonstration of how the eponymous, anarchistic villain (Rudolph Klein-Rogge), whose tentacles of power reach into every crevice of contemporary society, orchestrates the collapse of the stock market by masterminding the theft of. a secret trade contract and the manufacture of counterfeit banknotes before turning up at the stock market in disguise to wreak his final mischief.

The compulsive continuity of Lang’s editing throughout this opening sequence and the pitiless checkerboard view of the world implied in his overhead shots, displaying the combined precision of Griffith’s montage and Feuillade’s mise en scène, recall a key line from Thomas Pynchon’s great paranoid novel Gravity’s Rainbow half a century later “lf there is something comforting — religious, if you want-about paranoia, there is still also anti-paranoia, where nothing is connected to anything, a condition not many of us can bear for long.” Implicit in this formula is the notion that spiritual and philosophical as well as artistic coherence depends on connections, and the absence of apparent connections, yielding gibberish and chaos, makes paranoia a tempting alternative. Consequently, part of the function of Lang’s montage and mise en scène is to imply hidden connections in the world which the viewer’s imagination is invited to spell out.

In Lang’s next paranoid thriller, Spies (1928) , again starring Klein-Rogge as a Mabuse-like figure named Haghi, the two central graphic images are recurring close-ups of Haghi wreathed in cigarette smoke and a network of crisscrossing iron stairways and four-tiered balconies located just outside his secret headquarters. Apparently located somewhere inside a bank, this dense passageway also suggests a prison — an impression fostered the first time we see it when a prisoner “miraculously” saved from the gallows is delivered directly to Haghi’s lair as the latest recruit into his spy ring. Even odder, the appearances of an elderly nurse and Haghi’s confinement in a wheelchair intermittently suggest a hospital.

What’s “comforting,” in short, about both the close-ups of Haghi and the shots of the stairways is that they effectively explain everything in the plot — showing respectively how one figure controls the universe and how practically every important sector of institutional power (bank, prison, hospital) appears to be adjacent to his private chambers. Allegorically, one might say that both images suggest the nexus of Lang’s own power as artist-filmmaker, creating all these continuities and causal effects on his editing table and thereby implying that the satisfactions of conspiracy are closely allied to the empowerment of artistic control. The same implication comes to the fore in Blow Up (1965), whose hero-sleuth is an art photographer, and also in its audio spin-off, The Conversation (1974), when the moral qualms of a bugger about what his ,”evidence” might be used for persuades him to imagine a particular murder plot that gratifies his guilt-ridden Catholic conscience. And from another angle, one might argue that a craving for a coherent historical meaning in John F. Kennedy’s assassination is what goaded writer-director Oliver Stone into making JFK and also persuaded a good many people to buy its particular conspiracy theory –- an artistic impulse on both counts.

The same equation between control of the universe and artistic control is frequently evoked in Pynchon’s early fiction, and it also crops up significantly in one of the founding work of the French New Wave, Jacques Rivette’s Paris Belongs to Us (1960). (If Rivette’s title perfectly encapsulates the comfort of paranoia, the film’s opening epigram –“Paris belongs to no one” — sums up the despair of anti-paranoia.) But in these cases, where monumental mental quests to uncover secret connections and buried histories yield uncertain results, an intellectual and theoretical self-consciousness about paranoia imposes a certain ambiguity as to the degree to which conspiracy is conjured up in the imagination and desire of the beholder. In Rivette’s feature, intimations about a worldwide conspiracy crisscross with the faltering efforts of an ambitious but under-funded theater group to stage a production of Shakespeare’s Pericles, and similar contrapuntal effects between masterplots and collective artistic endeavors are found in Pynchon’s V and The Crying of Lot 49.

Paris Belongs to Usis visibly influenced by Lang as well as by Robert Aldrich’s noir thriller Kiss Me Deadly (1955) -– a violent detective story in which anxieties about the atomic bomb are suggestively dovetailed into the myth of Pandora’s Box — helps to clarify the aesthetic lure of conspiracy theories by positing the color white, the fusion of all other colors, as the ultimate paranoid expression, the “final solution” for rendering the illegibility of modern life in legible form. In Aldrich’s film, the quest is for a strongbox containing plutonium that emits a blinding white light when opened and ultimately unleashes a nuclear holocaust that concludes the movie. Similarly, a pivotal sequence in Paris Belongs to Us shows several characters watching the Tower of Babel sequence in Lang’s Metropolis until the film suddenly breaks and they’re confronted by the gaping stare of a blank white screen. The Tower of Babel myth evokes Pynchon’s notion of anti-paranoia — the chaos arising from the multiplicity of languages and the breakdown of communication — just as surely as Pandora’s Box posits the solution to that impasse in apocalyptic terms. Like the whiteness of the bathroom where The Conversation’s bugger arrives at his own bloody conclusion — a climax that can be traced back to the bathroom murders of Les Diaboliques and Psycho — these white revelations become in effect blank sheets of paper on which the paranoid message gets written.

As can be seen from its title, Gravity’s Rainbow, which ends with the phrase “Now everybody –” (referring both to collective song and to universal annihilation) combines these antithetical possibilities within its own quest narrative. The quest of hero Tyrone Slothrop for his own origins — in order to explain the enigmatic connection between his sexual erections and the unpredictable targets of V-2 bombs in England during World War II, which his erections predict — yields first the makings of a paranoid plot, then a free-fall of narrative chaos. It’s a movement that apes the trajectory of a V-2 bomb both in its concerted rise and in its scattered fall, before arriving in the present for the climactic coda.

It’s probable that the most long-lasting mode of paranoia entertained during this century, apart from fear of technology, is the cold war, which effectively lasted for almost half of that century. Practically all the themes discovered by Lang in the 20s got extended and elaborated in relation to fears of the alleged Communist Menace in the 50s and 60s. Consider the hidden lairs, disguises, and high-tech gadgets and weaponry in the James Bond movies and their many spin-offs, or the elaborate brain-washing techniques in The Manchurian Candidate (1962). But when it came to surveillance, the fear of being spied on often became inverted in order to rationalize the sort of climate in which blacklists and McCarthyism flourished.

In Leo McCarey’s deranged yet often moving My Son John (1952), a middle-American mother and father (Helen Hayes and Dean Jagger) gradually discover that their wayward intellectual son (Robert Walker) has become a Communist spy, and the clinching piece of evidence is a key belonging to John that the mother accidentally intercepts. It proves to be the key to the Washington apartment of a woman recently convicted as a Communist spy — a clear allusion to the Judith Coplon spy case that garnered plenty of scare headlines in that period.

One odd aspect of the paranoia in My Son John is the way surveillance is regarded not as a threat but as a benign necessity. In a climactic sequence, a sympathetic and patriarchal FBI agent (Van Heflin) shows his cohorts a recent film of John’s mother confirming her suspicions about her son by using the telltale key to open and enter the woman spy’s apartment –- a scene recorded by no less than half a dozen hidden movie cameras that capture her “secret” journey to the site and even the horrified expression on her face from inside the apartment after she opens the door. What was frightening to audiences in 1952 was her discovery that John was a Red spy; but what seems equally frightening 47 years later is the 50s audience’s casual endorsement of that sort of government surveillance. After Watergate, taking such things for granted would radically change, and from the 70s onward, when conspiracy theories became coin of the realm in such thrillers as All the President’s Men, The Parallax View, Night Moves, and The Conversation, surveillance in general and government surveillance in particular began to seem increasingly ominous, a tendency culminating in Enemy of the State.

Haghi’s secret lair in Spies may be associated with public institutions such as banks, prisons, and hospitals, but not directly with the government, and the same could be said of Mabuse’s various haunts, except by implication. But the comparable high-tech lair of the villain in Enemy of the State is the headquarters of the National Security Agency, and the principal paranoid fear in both this movie and The Conversation is neither mind control nor nuclear holocaust but the loss of privacy. Just as the bugger hero of The Conversation – who winds up being bugged himself –- is psychologically stripped naked by surveillance and winds up stripping his own apartment in search of concealed microphones, the lawyer hero of Enemy of the State tracked by the National Security Agency literally has to strip to his underwear at one point in order to escape his pursuers.

Harking back to The Conversation through the presence of Gene Hackman and his warehouse headquarters, Enemy of the State seems to be saying that the government’s tabs on us strip us bare.Arguably, the same sort of tabs kept on us as consumers by big business -– demographical, psychological, sexual, economic –-might be an even greater cause for alarm if one decides that the interests of government and those of big business are not exactly strangers to one another. (A key moment of crisis for the lawyer hero of Enemy of the State occurs when his credit cards no longer work; his loss of purchasing power is made to seem at least as calamitous as the loss of his clothes.)

As long as capitalism is viewed as our friend and government and media are construed as our enemies (rather than as adjuncts of big business, a more logical premise), the possibilities of paranoid thrillers in which tycoons play the Mabuse role may seem relatively remote. But in fact we’ve already had a slew of these, including The Conversation, and Cutter’s Way is one of the best 80s examples that springs to mind -– a movie that dramatizes the helplessness of isolated citizens who try to go up against omnipotent power brokers. That film harked back to the paranoia of the 60s by focusing on a small circle of friends, two of them Vietnam war vets, rather than a single individual.

The reluctance of more recent thrillers to target the same sort of corporate entities that finance them seem to limit some of the genre’s richer possibilities. Rather than offer the paranoid hypothesis that this has anything to do with censorship, I would tentatively suggest that it’s one of the ideological biases of our present and triumphantly post-Communist period that anything and everything can be held responsible for the potential loss of our freedom except for the profit motive of large corporations. And even though we don’t have stereotypical bomb-throwing anarchists or Communist spies to target any longer, we still have the federal government and the media. Yet once we start to get paranoid thrillers again in which the forces behind those entities are defined, we might find our way back to the Golden Age of Mabuse.