From the October 2008 issue of Artforum. (This is also reprinted in my 2010 collection, Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia.) — J.R.

No major figure in postwar Japanese cinema eludes classification more thoroughly than Nagisa Oshima. The director of twenty-three stylistically diverse feature films since his directorial debut in 1958, at the age of twenty-six, Oshima is, arguably, the best-known but least understood proponent of the Japanese New Wave that came to international prominence in the 1960s and ’70s (though it is a label Oshima himself rejects and despises). Given the size of his oeuvre and the portions that remain virtually unknown in the West — including roughly a quarter of his features and most of his twenty-odd documentaries for television — the temptation to generalize about his work must be firmly resisted. Read more

This beautiful photograph, which I’m told has never been published before, was given to me by his maternal niece Rina Chakravarti in Toronto, at the Lightbox, shortly before I gave an introduction to a restored, gorgeous print of Ghatak’s 1960 masterpiece, The Cloud-Capped Star. It was taken taken in 1946 in Baikunthapur, Madhya Pradesh.

As one can (arguably) see from the photo below, of Niranjan Roy — the male lead of The Cloud-Capped Star, who plays the character Sanat — there’s a certain resemblance. [9-11-12]

Read more

From Scenario, Spring 1999, Vol. 5, No. 1. -– J.R.

The recent video release and cable premiere of Louis Feuillade’s silent French serial Les Vampires (1915- 1916), making it widely available in the United States for the first time in 80-odd years, clarifies the origins of the paranoid thriller in a particularly acute way. All the basic elements that we associate with movie conspiracies are fully present in Les Vampires, at least in some rudimentary form: high-tech surveillance techniques, secret lairs, hidden wall panels, intricately concealed weapons, elaborate disguises, diverse forms of mind and memory control.

This arsenal of paraphernalia and technology, suggesting that the ordinary world isn’t quite what it appears to be and that everyday life is full of concealed plots and hidden dangers, is surely a staple of this century that didn’t have to wait for video surveillance or the digital revolution before it took over people’s imaginations. Though the political casts of the designated villains fluctuate wildly according to the ideology of the country and period — ranging from the anarchist Vampire gang to the red spies of Cold War thrillers, to the nearly invisible capitalist tycoons of Cutter’s Way (1981), to the smug government bureaucrats in the significantly titled Enemy of the State — the evil designs remain more or less the same. Read more

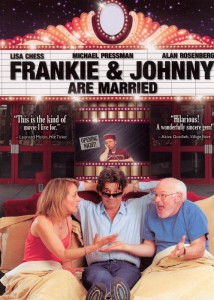

From the Chicago Reader (December 10, 2004). — J.R.

A fascinating blend of fiction and documentary, this feature by Michael Pressman chronicles his emotionally complicated LA production of Terrence McNally’s play Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune. Pressman’s wife, Lisa Chess, costarred in the show with his old friend Alan Rosenberg, until difficulties with Rosenberg convinced Pressman to take over the part himself. These three and many other people (including Kathy Baker and Hector Elizondo) play themselves in the movie, which only begins to suggest the ambiguities Pressman exploits to the utmost. Emerging from all this is a fascinating look at the nuts and bolts of theater work and an often hilarious depiction of how personal neuroses help and hinder it. R, 95 min. (JR) Read more

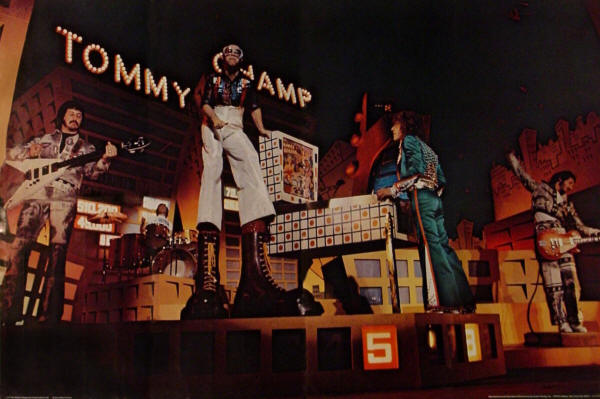

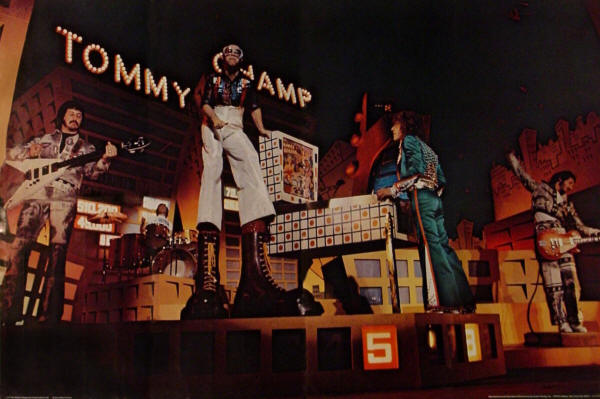

From Monthly Film Bulletin, April 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 495). — J.R.

Tommy

Great Britain, 1975 Director: Ken Russell

Cert-AA. dist-Hemdale. p.c—The Robert Stigwood Organisation.

exec. p-Beryl Vertue, Christopher Stamp. /;Robert Stigwood, Ken

Russefl. assoc. p-Harcy Benn. p. manager-John Comfort. asst. d-

Jonathan Benson. sc-Ken Russell. Based on the rock opera by Pete

Townshend and the Who. addit. Material–John Entwistle, Keith Moon.

ph–Dick Bush, Ronnie Taylor. In colour. sp. ph. effects–Robin Lehman.

ed—Stuart Baird. a.d–John Clark. set dec–Paul Dufficey, Ian Whittaker.

sp. Effects–Effects Associates, Nobby Clarke,_Carygra Effects. m/songs–

“Captain Walker Didn’t Come Home”. “It’s a Bov !” “’51 is Going to be a

a Good Year”, “What About the Boy ?”, “See Me, Feel Me”, “The

Amazing Journey”, “Christmas”, “The Acid Queen”, “Do You Think

It’s All Right?”, “Cousin Kevin”, “Fiddle About”, “Sparks”, “Pinball

Wizard”, ‘Today It Rained Champagne” ,”‘There’s a_Doctor” , “Go to the

Mirror”, “Tommy Can You Hear Me !’” “Smash the Mirror”, “I’m Free”,

“Miracle Cure”, “Sensation”, “Sally Simpson”, “Welcome”, “Deceived”,

“Tommy’s Holiday Camp”, “We’re Not Gonna Take It”, “Listening to

You” by Pete Townshend and The Who [Roger Daltrey,John Entwistle,

Keith Moon, “Eyesight to the Blind” by Sonny Boy Williamson. m.d–

Pete Townshend. musicians-Elton John, Eric Clapton, Keith Moon,

John Entwistle, Ronnie Wood, Kenny Jones, Nicky Hopkins, Chris

Stainton , Fuzzy Samuels, Caleb Quayle, Mick Ralphs, GRaham Deakin,

Phil Chen, Alan Ross, Richard Bailey, Dave Clinton, Tony_Newman,

Mike Kelly, Dee Murray, Nigel Ollson, Ray Cooper, Davey_Johnstone,

Geoff Daley, Bob Efford, Ronnie Ross, Howie Casey. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 17, 1989). — J.R.

APARTMENT ZERO

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Martin Donovan

Written by Donovan and David Koepp

With Colin Firth, Hart Bochner, Dora Bryan, Liz Smith, Fabrizio Bentivoglio, James Telfer, Mirella D’Angelo, Juan Vitali, and Francesca d’Aloja.

Although it qualifies technically as an American movie, Martin Donovan’s ambitious, disturbing thriller Apartment Zero is one of those international hodgepodges that are somewhat disorienting almost by definition. Set in Buenos Aires, made with actors and technicians from three continents, and filmed in English by an Argentinean director who has lived mainly in Italy and England since the 70s, it has the sort of multinational sprawl that only a strong script and a forceful style could hold together. Fortunately, Apartment Zero has both script and style in spades. It may not be to everyone’s taste, but to me it’s an exciting piece of controlled cinematic delirium.

I first encountered this movie at a midnight screening at the Berlin Film Festival last February, having been guided to it by a perceptive rave in Variety by Todd McCarthy. Ever since then I’ve been wondering when and how it would eventually turn up in Chicago. It lacks most of the usual commercial calling cards (big stars, lovable nerds, genre cliches, babies, body switches, Spielberg lighting), it was passed up by the New York and Chicago film festivals, and it didn’t seem the sort of picture that Vincent Canby would like. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 3, 2003). — J.R.

Broadly speaking, this is Richard Linklater’s French Cancan — that is to say, a humanist’s joyful exploration of the musical in which the actors’ personalities resonate as much as the characters they play. Or maybe it’s what Jean Renoir might have come up with if he’d remade Don’t Knock the Rock and cast 12-year-olds as the musicians. Though this seems like a personal film, Linklater was hired to direct a cannily commercial script by Mike White, about a rock ‘n’ roll loser (Jack Black) who, fired from his job and his band, impersonates his wimpy substitute-teacher roommate (White) to land a teaching position at an upscale elementary school. This infantile character hasn’t got a thought in his head except for rock music, but somehow he becomes a model teacher, and through stealth and sheer perseverance he turns his fifth-grade class into an inspired gang of rockers. The kids, all real musicians performing, are wonderful, and so is Black; Joan Cusack is both charming and funny as the principal. 108 min. Century 12 and CineArts 6, Chatham 14, City North 14, Crown Village 18, Ford City, Gardens 1-6, Gardens 7-13, Lawndale, Lincoln Village, Norridge, North Riverside, 600 N. Read more

From the November-December 1976 Film Comment and exhumed now mainly as a telling time capsule of this period in the world of English film criticism. I’m still indebted to Laura Mulvey for introducing me to Zoo, or Letters Not About Love in her own list, which has subsequently become a touchstone for me.

For illustrations, I’ve selected the first film cited in each list whenever possible, even when there’s no particular significance to the order (when I couldn’t come up with one for The Nightcleaners, at least until Ehsan Khoshbakht — see below — furnished me with production stills or framegrabs; I accorded the late Claire Johnston two others)….Because of a scanning error and oversight, I originally had to omit two entries, those of David Pirie and Paul Willemen, which are now included. In the remaining 27, I’ve corrected a few typos for the first time, and accidentally introduced a few others, but thanks to the generous efforts of my good friend and best proofreader, Ehsan Khoshbakht, on December 4, 2014 (as well as Adrian Martin three days later, who caught a few more glitches), these are now corrected, and five additional illustrations (again, courtesy of Ehsan) have been added. Read more

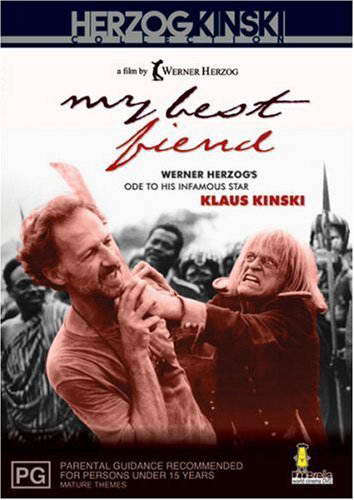

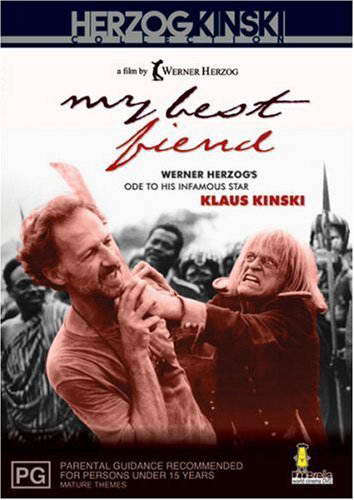

From the Chicago Reader (February 11, 2000). — J.R.

My Best Fiend

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed and written by Werner Herzog.

What’s the difference between artistry and bravado? This isn’t a question I generally feel inclined to ask, but I’m compelled by the work of Werner Herzog, who scrambles the two until it’s difficult to tell which is which. My Best Fiend — Herzog’s documentary feature about his tumultuous collaborations with Klaus Kinski, the mad actor with whom he made some of his most notable films — also compels questions about Kinski’s bravado and artistry, and suggests that it might not always be easy to distinguish his from Herzog’s.

One might call My Best Fiend, which is playing this week at Facets, the art-movie equivalent of writer-director Blake Edwards’s Trail of the Pink Panther. Edwards and Peter Sellers reportedly were at each other’s throats throughout their many collaborations on Pink Panther comedies — largely, it appears, because of Sellers’s hyperbolically neurotic behavior. Herzog and Kinski had a similarly volatile relationship, which ended only after Kinski died, in 1991. Herzog got his revenge by releasing outtakes of his difficult star, much as Edwards continued to fiddle around with unreleased footage of Sellers as Inspector Clouseau in Trail of the Pink Panther. Read more