From the Chicago Reader (December 21, 1990). — J.R.

If my paranoid suspicions are correct, Hollywood has embarked on a 12-year plan regarding the public consumption of trailers. The plan, which has become fully apparent to me over the past year, will come to fruition in the year 2000, and its basic goal, as I see it, is to turn movies themselves into full-fledged commercials that people will pay money to see.

When Back to the Future II ended with a trailer for Back to the Future III, it was a harbinger of what’s to come. The ever-increasing proliferation of sequels has already accustomed the public to the notion that any hit movie eventually becomes, at least retroactively, an advertisement for its inevitable successor. Now, through a three-point program that might be termed standardization-infiltration-expansion, Hollywood is force-feeding us a diet of trailers in an apparent effort to alter our modes of perception. Most movie trailers are now designed to resemble one another as closely as possible, from the discontinuous, scattershot cutting to the near-subliminal card of credits flashed at the end. They appear in a variety of fresh contexts — at the beginning and end of videotapes, on “commercial-free” cable channels, and as integral parts of some features, like the aforementioned Back to the Future II — and they crop up so repeatedly in their more traditional venues, in movie theaters and on network TV, that we may come to know certain trailers as intimately as we know certain family members.

Already there are many alarming consequences to this trend. Many of the best things to be found in this year’s movies — such as Brando’s performance in The Freshman and Eastwood’s in White Hunter, Black Heart; the intricacies of plot and character in Enemies, a Love Story, Rembrandt Laughing, Twister, Miami Blues, The Plot Against Harry, Pump Up the Volume, The Icicle Thief, and The Russia House; the play-within-the-film in Jesus of Montreal; the extended hommage to Tati’s Playtime in The Exorcist III (a very lengthy take in a hospital corridor); the play with philosophical ideas in Roger Corman’s Frankenstein Unbound; the leisurely uses of landscape in Quigley Down Under and Dances With Wolves; the slow camera movements in The Raggedy Rawney — are impossible to represent in any adequate way within the telegraphic punchiness of trailers, especially current ones, because these things have little or nothing to do with speed and instant intelligibility. Many people I know stayed away from these films either because they had no trailers to represent them or — more often –because the trailers they did have were misrepresentative turnoffs that offered not the slightest clue to what was good about them.

1990 was clearly the year when trailer-consciousness reached a new high in this country. Even TNT, Ted Turner’s cable channel, entered the act with a new retrospective feature called Trailer Camp, which serves to remind us how relatively varied and individual trailers could be back in the 30s, 40s, and 50s — when “trailers” was still mainly a trade term for what the public usually called “previews” or “prevues” of “coming attractions.” I don’t mean to suggest that trailers didn’t have their own clichés back then as well — only that they were a bit less ruthless in making mincemeat out of the movies they were advertising.

Then as now, most trailers were made while the features themselves were still in production, and most were put together by publicity people at the studios rather than the films’ directors. (An occasional consequence of this practice is that some scenes in trailers do not appear in the final films.) But there were exceptions to this rule, and some of them are quite memorable: Orson Welles directed his own trailer for Citizen Kane, at the urging of his cinematographer Gregg Toland, and the result (available on the Criterion deluxe edition of the film on laserdisc) is a delightful short film in its own right. In keeping with his radio persona of that period, Welles narrates offscreen and never appears; the other actors are introduced by him in street clothes on RKO soundstages, surrounded by the film’s props. Not a single shot in the trailer comes from the film itself, but apart from its avoidance of the film’s gloomier aspects, it is an honest piece of ballyhoo that gave audiences some notion of what to expect while skillfully piquing their curiosity. (Sadly, when Welles put together another trailer for the U.S. release of his F for Fake in 1974 –another enjoyable autonomous work, this one about 12 minutes long — his outraged distributor refused to process it; this gem survives today only on an undistributed videotape preserved by one of Welles’s associates.) Alfred Hitchcock’s trailer for Psycho, another gem (also available on laserdisc), has the Master conducting the viewer through a guided tour of the film’s major locations.

We rarely find this sort of personal touch in trailers nowadays, when most creative control belongs to bankers rather than studio heads. Today the main idea seems to be shoving peekaboo fragments at the spectator that can only convey at best a very jumbled impression, and usually reduce every movie that’s not a comedy or an action film into something resembling a horror show. (The rapid resume and flash-forward that frame each week’s Twin Peaks episode basically adopt the same approach.) If the only prior knowledge you have about The Russia House is its trailer, to cite one recent example, you’re bound to know very little about either the plot or characters; all you get is a few bursts of action and some isolated slivers of story — shards of a dream about the film perhaps, but scarcely a proper introduction. Just as some movie titles get reduced to a word or two when they have to fit onto tiny marquees (a problem that worried W.C. Fields back in 1941, when he was afraid that his Never Give a Sucker an Even Break would be reduced to “Fields–Sucker”), scenes typically get pared down to sound bites, with the implication that if you can’t get your concept across in three seconds flat, people won’t be interested. But this assumption is an insult to our intelligence: how can we be interested in anything except sound bites if sound bites are all that’s being offered for our inspection? On reflection, maybe the root idea is that we aren’t supposed to inspect the merchandise at all; we’re merely supposed to decide on the basis of subliminal flashes whether or not we want to be raped by it.

Which brings me back to my paranoid scenario about Hollywood’s 12-year plan. Once we start thinking about subliminal or near-subliminal messages in trailers, it’s also worth considering ads for nonmovie products within movies, which are perhaps even more indicative of what’s to come. Think of all those scads of product plugs that precede the trailer in Back to the Future II, all slyly worked into the plot, for corporate advertisers like AT&T, Black & Decker, CBS Records, Mattel, Nike, Pepsi, and Pizza Hut.

The most interesting book about current moviemaking practices to come out this year was Seeing Through Movies, a fascinating and informative collection of essays edited by Mark Crispin Miller, available from Pantheon. One of the more interesting pieces in it is one about “product placement,” written by Miller himself. He begins by recalling the nationwide protest that was heard in 1957 when a company called Subliminal Projection claimed — falsely, as it later turned out — that it had substantially boosted sales at the concession stand of a movie theater in Fort Lee, New Jersey, by injecting into the feature (Picnic) subliminal ads for Coca-Cola and popcorn every five seconds for one three-thousandth of a second. At the time, members of Congress, religious leaders, the National Association of Radio and Television Broadcasters, and the New York state senate, among others, called for a ban on subliminal advertising. But as Miller points out, nobody today even thinks of protesting (much less banning) the widespread use of product placement in feature films, although this practice functions rather similarly to subliminal ads and may be just as effective as they were said to have been.

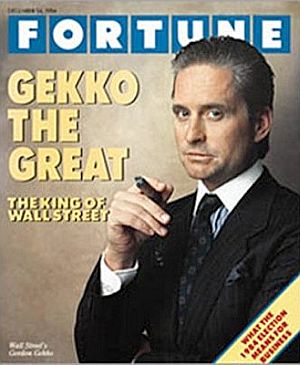

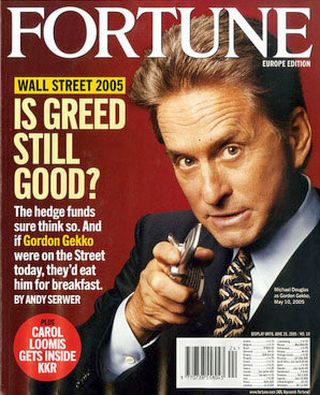

I won’t try to summarize the findings of Miller’s 60-page essay (most or all of which appeared in the Atlantic several months ago), but a few of his characteristic examples are worth noting. Murphy’s Romance (1985) not only contains paid-for plugs for Coke, Purina, Heinz steak sauce, Wesson oil, Nike, Huggies, Vanish toilet-bowl cleaner, Fuji film, Miller beer, Ivory liquid soap, Extra-Strength Tylenol, and Campbell’s soup; it also works direct references to at least three of these brand names into the dialogue. The much-admired Bull Durham contains plugs for Pepsi, Miller, Jim Beam, Oscar Mayer, “and a host of Alberto-Culver products.” Wall Street, which purports to be an attack on unethical market practices, contains plugs for Molson Light, Pepsi, and Fortune magazine; in the case of the latter, a double plug — a reference in the script to Fortune as “the bible” and a shot of villain Gordon Gekko (Michael Douglas) on the cover — won Twentieth Century Fox two free ad pages worth $94,000 for the film in the same magazine. The plug for Molson Light was used as a detail in characterization; it’s what the hero’s honest and principled working-class father (Martin Sheen) orders in a saloon.

Other, more recent films incorporate paid-for plugs just as prominently. At a recent promotional screening for Home Alone in Chicago, a spokesperson for a product-placement agency proudly called attention to an extended plug for Budget Rent a Car worked into the plot via John Candy, and added that Candy makes a point of pushing Budget in several of his movies. And if one adds to this the ads for products that are now routinely tacked onto the beginnings of features, both in theaters and on videos, and the multiple spin-offs of sales items that accompany the release of films from Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles to Dick Tracy to Godfather III, the degree to which multinationals are now hawking their products through their own movies — or else renting out ad space inside someone else’s — makes the notion of feature-length ads in theaters seem a lot closer than it once did.

Admittedly, some spectators will knowingly and happily flock to ads for their own sake if they’re placed in the proper context. It’s significant that the most popular and expensive single event at the Chicago International Film Festival year after year is a selection of TV commercials from all over the world. On the other hand, many audiences resent being subjected to ads after spending $7 for a movie — enough audiences, at any rate, to have inspired the Disney people this year to restrict their bookings to theaters that won’t show ads. But is this done out of respect for the audience, or to limit the ads seen to those inside the Disney movies, thereby maximizing their effectiveness? After all, Disney’s biggest money-maker of 1990, which may even prove to be their biggest hit to date, was Pretty Woman, a shopping movie if there ever was one.

Perhaps if the multinational marketers eventually have their way, we will have feature-length trailers, packed with product placements for items that can be sold in the lobby on our way out of the theaters. By then the White House and Capitol will have moved from Washington, D.C., to Hollywood in order to consolidate the official merger between government and show biz. The weekly count of box-office grosses in newspapers will take the place of the presidential popularity polls, and our elections will consist of consumer surveys. Entertainment Tonight will supplant the evening news (already, on ABC at least, the events of the world and entertainment news are allotted equal amounts of time on weeknights), which will mean that wars and other military ventures will be launched, conducted, and evaluated according to their ongoing entertainment value (with the invasion of Panama as the working model), complete with cleverly inserted plugs for the Pentagon’s latest weapons. (We won’t have to worry about commercial interruptions anymore, because TV and movies alike will consist exclusively of commercials.) Future presidents in the Reagan mold won’t have to quote from movies (“Make my day”) because the movies will be quoting the presidents, who will soar into office on the basis of their own pithy sound bites (“Read my lips,” “I can take the heat”).

With such a system firmly in place, all the movies we’ll see in theaters and on video will be separate feature-length trailers for a single blockbuster that’s perpetually in production — a blockbuster that will never be completed because the economic advisers will soon realize that after years of such hoopla, no movie could possibly live up to so much buildup and hype. By then, however, it won’t matter, because people will be perfectly happy with these enticing trailers. (Unkept promises are always the sweetest.) A suggested title for the blockbuster-in-progress: The Big Dream. Maybe, if we all wish real, real hard, that’s the sort of package that Santa will have in store for us by Christmas 1999.