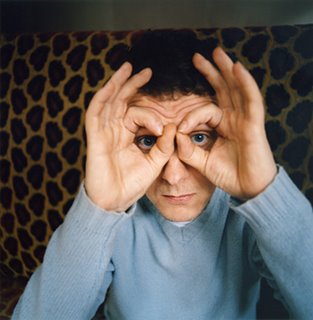

The following short essay was commissioned by the Walker Art Center in early 2007 for a brochure accompanying a retrospective (“Michel Gondry: The Science of Dreams”) presented between May 11 and June 23, and a Regis Dialogue that I conducted with him on June 23. –J.R.

What’s sometimes off-putting about the postmodernity of music videos is tied to both the presence and absence of history in them — the dilemma of being faced simultaneously with too much and too little. On the one hand, one sees something superficially resembling the entire history of art — often encompassing capsule histories of architecture, painting, sculpture, dance, theater, and film — squeezed into three-to-five-minute slots. The juxtapositions and overlaps that result can be so violent and incongruous that the overall effect is sometimes roughly akin to having a garbage can emptied onto one’s head. Yet on the other hand, radical foreshortenings and shotgun marriages of this kind often have the effect of abolishing history altogether, making every vestige of the past equal and equivalent to every other via the homogenizing effect of TV itself. Back in 1990, sitting through nearly eight hours of a touring show called “Art of Music Video,” I was appalled to discover that the two most obvious forerunners of music videos, soundies from the 40s and Scopitone from the 60s, were neither included in the show nor even acknowledged in its catalog’s history of the genre. So it might be argued that the genre reinvents the cinema and abolishes it in the same gesture.

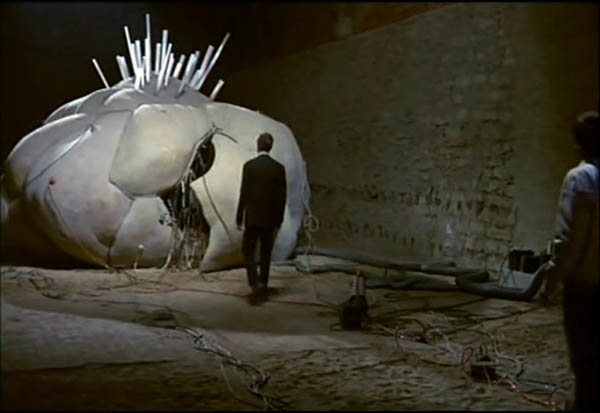

This paradox constitutes a major challenge faced and posed by Michel Gondry’s work — not just in his music videos, but also in his shorts and features, many of which employ both technical wizardry involving various kinds of special effects and animation and intricate narrative setups. Like the heartbroken characters in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind who want their memories erased, his work can be seen as a succession of strategies for devising ways of coping with overload. Most often this is done conceptually, through some form of metaphysics, or formally, through some other kind of shaping and filtering. Sometimes he contrives to do both, such as when he ricochets in his Everlong video between a sleeping figure and a dream, before contriving to combine the two in the same image.

Proceeding from the first of Gondry’s half-dozen music videos for Bjork, Human Behavior (1993), to his somewhat related first feature, Human Nature (2001), or from Human Nature to his forthcoming Be Kind Rewind and Master of Space and Time, by way of several shorts as well as Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) and The Science of Sleep (2004), Gondry’s ongoing adventure seems intimately tied to both overarching metaphysical conceits as well as to the specific underpinnings of personal memories. And insofar as his work has continuing themes — even when it’s written or cowritten by others, most notably by Charlie Kaufman (on Human Nature and Eternal Sunshine) — one of these appears to be the particular alliances made between personal memories, metaphysical conceits, and technical expertise. Such alliances are also plentiful in the early features of Alain Resnais, one of Gondry’s apparent masters, where the diverse provocations of Hiroshima mon amour, Last Year at Marienbad, Je t’aime, je t’aime, and Providence all seem grounded in personal necessity. Yet as Gondry shows in his uncharacteristic 2006 documentary Dave Chapelle’s Block Party, sometimes his strategy is to lay out as ego-tripping auteur and simply respect the integrity of a given event.

Once he becomes, for the first time on a feature, sole writer as well as director, on The Science of Sleep, it becomes clearer that he’s a soft surrealist — by which I mean a surrealist with a small s. Working with reconfigurations of the autobiographical materials found in I’ve Been Twelve Forever (2003), a feature-length documentary about him, including some of his sources and working methods, he certainly cultivates and harvests his own obsessions, but generally does so without the aggressiveness of a David Lynch — meanwhile moving just as implacably inward as Lynch does, away from society and into his own dreams. So he also lacks the sociopolitical agenda of a big-S Surrealist such as Luis Buñuel, who manages to move inward while assaulting society at the same time. Yet there’s still plenty of elbowroom in Gondry’s progressive program for playful, irreverent satire. It’s a respectable calling; the Marx brothers, Dr. Seuss, and Richard Lester are all charter members of the same persuasion.