From the Chicago Reader, April 2, 1999. —J.R.

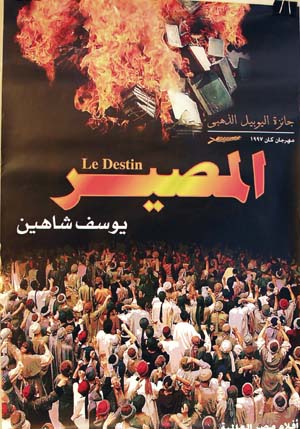

Destiny

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Youssef Chahine

Written by Chahine and Khaled Youssef

With Nour el-Cherif, Laila Eloui, Mahmoud Hemeida, Safia el-Emary, Mohamed Mounir, Khaled el-Nabaoui, Abdallah Mahmoud, and Ahmed Fouad-Selim.

The Adopted Son

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Aktan Abdikalikov

Written by Abdikalikov, Avtandil Adikulov, and Marat Sarulu

With Mirlan Abdikalikov, Albina Imasmeva, Adir Abilkassimov, Bakit Zilkieciev, and Mirlan Cinkozoev.

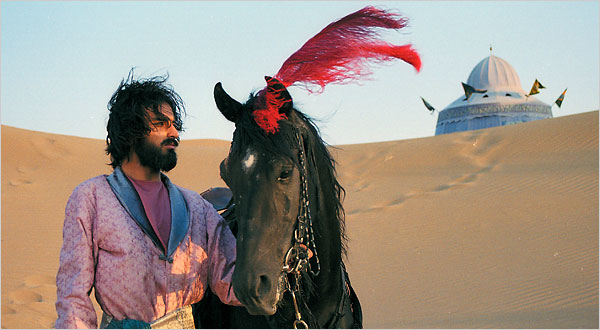

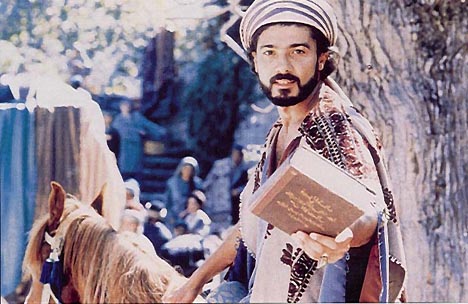

Apart from their exoticism, Youssef Chahine’s Destiny and Aktan Abdikalikov’s The Adopted Son don’t have much in common. Destiny is the 35th film by Chahine, a 73-year-old writer, director, and sometime actor who’s generally agreed to be the major figure in the history of Egyptian cinema. His subject here is Averroes (1126-1198), a dissident Spanish-Arab philosopher best known for his commentaries on Aristotle, and his film resembles a Hollywood period spectacular — exuberant, packed with action, and positively overflowing with energy. The Adopted Son is both the first independent feature ever made in Kyrgyzstan — a former Soviet republic in central Asia — and the first feature of 42-year-old writer-director Abdikalikov, who cast his own teenage son in the title role. It’s shot mainly in an exquisitely modulated black and white, though it periodically shifts to color, always with great dramatic effect. Its central focus is childhood and nature in a contemporary rural village, and its main event is the boy’s discovery about halfway through that he was adopted through an ancient local tradition in which parents of a large family offer a male baby to a childless couple after he’s been weaned.

By American standards, The Adopted Son (1998) qualifies as an art film as does Destiny (1997). Chahine’s colorful epic calls to mind certain MGM movies of the 50s, but that apparently counts for nothing given that it comes from Egypt — the only plausible reason it’s showing at the Music Box rather than McClurg Court. Similarly, one could argue that the only reason The Adopted Son is playing at Facets Multimedia and not at the Music Box is that it comes from Kyrgyzstan — anything from a country that difficult to spell must be esoteric. That it’s from the former Soviet Union only compounds the confusion, since we no longer know how to label the various people who live there. (Incidentally, both movies are French coproductions, a reflection of how much more open France’s film culture is to the aesthetics of MGM movies of the 50s and to contemporary art movies from the far-flung corners of the world.)

I don’t mean to suggest that movies from cultures as remote as these wouldn’t pose challenges for casual moviegoers, who might think watching them would be too much like going to school. But such challenges might often prove liberating and exciting — a vastly different experience from watching, say, The Matrix, which claims to be offering a new slant on how the universe works, though it’s recycling elements from just about every other SF action movie in recent memory. If any new ideas find their way into the mix, they’re inevitably obscured by all the shopworn trimmings.

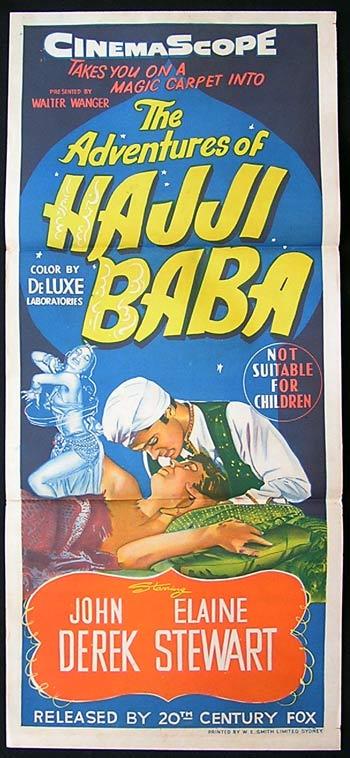

Destiny may intermittently remind one of 50s studio productions as good as The Adventures of Hajji Baba or as mediocre as Kismet — it recalls a house style I associate mainly with MGM and secondarily with directors such as Anthony Mann, Richard Thorpe, Don Weis, Vincente Minnelli, George Sidney, and Mervyn LeRoy. Part of what makes this movie excitingly different is that Chahine has found a meeting ground for what he draws from Hollywood and what he draws from his own culture — a place where they can happily coexist and learn from each other.

MGM in the 50s furnishes me with one personal entry route into the film, and being Jewish provides me with another. The usual ethnocentric position is to see Jewish and Arab cultures in the Middle East at loggerheads, but one can also find similarities in body language, vocal inflections, complexions, forms of ironic humor, and many other subtle markers of common ancestral roots. It would be presumptuous of me to think that every viewer could find a way into Egyptian cinema through these particular routes, but all sorts of potential entry points can be found if viewers are inclined to look for them.

One entry point, for instance, might be Chahine’s personality. I’ve seen him at several festivals in recent years, and he’s as charismatic and outrageous as Samuel Fuller was. A short, wiry firecracker, he also makes no bones about being bisexual; the third movie in his autobiographical trilogy, Alexandria Always and Forever (1989), is comically frank about his sexual attraction to one of his young male leads and features the two of them doing an amorous tap dance on a studio set. Destiny is clearly an act of courage in the face of Islamic fundamentalism, and one of its acts of defiance is to view women and men as equally desirable.

Another such act is viewing genre boundaries with an equal amount of liberalism. Chahine was asked in an interview, “Is it fair to say that Destiny is a musical?” He replied, “In a single day, I expect to cry, laugh, dance, sing. I may even be locked up in jail. A film should contain all those things. What matters is style and pace. One of the things I found most painful is when fundamentalists say they want to stop artists singing and dancing. That’s serious. It is extremely serious….The streets of Cairo are full of laughter. People have [become] too serious in the West. Though there’s plenty to be serious about. I think you’re in a worse mess than we are. People are all mixed up about the difference between civilization and technology. In the Arab world, people are exceptionally civilized. They possess nothing, but what they’ve got they’ll give you with pleasure.”

What’s refreshing about such cultural effusions is the striking contrast they provide with American film culture, whose tastemakers have decided that the musical is dead and we’re all much happier sitting through explosions, mutilations, and cascades of broken glass. If the characters in The Mod Squad periodically broke into song, that movie would surely be more bearable — even if they couldn’t carry a tune. How lucky people are in India and Egypt, where they haven’t become sophisticated like us and decided that musicals are passé.

I’ve seen seven of Chahine’s films and sampled a couple of others — most of them at a complete retrospective held in Locarno in 1996 (perceptively written about by Dave Kehr in Film Comment). But I haven’t seen the immediate predecessor of Destiny, The Emigrant (1994), a story of the biblical Joseph that was banned in Egypt under pressure from fundamentalists after an estimated 900,000 people saw it (the stated reason was that it was illegal to represent a prophet in a film). One of the key inspirations for Destiny — which ends with all of Averroes’s books in Andalusia being burned by the caliph as a concession to fundamentalist groups — was clearly Chahine’s own experience. If I’m not mistaken, the books we see burning in the final sequence are modern volumes rather than medieval manuscripts, which is part of the movie’s point. (Averroes’s writings survived because some of his followers copied them and sent the copies to Egypt — the medieval equivalent of copying films on video today, perhaps the major way the film legacy of the late 20th century is being preserved.)

That Averroes was a humanist whose ideas went on to influence Western as well as Islamic thought and that two of his followers were sons of the caliph are also part of Chahine’s inspiration: the film’s closing motto is “Ideas have wings. No one can stop their flight,” and Chahine has expressly stated that his movie is addressed to everyone, not simply to Egyptians or Islamic fundamentalists. “Yes, this film is a drama, it’s a western, it’s [Alexandre] Dumas [whom he read prior to shooting], whatever, but it’s also a call to resistance.”

Chahine grew up speaking four languages, and as a teenager, after the end of World War II, he came to America to study theater directing at the Pasadena Playhouse, an experience recounted in his Why Alexandria? (1978). So universality is not merely part of his aim but part of his cultural baggage. He makes the visual style of Destiny universal not just through being familiar with the tropes of both Hollywood and Egyptian cinema (the latter of which he helped to invent), but also through his gift for pageantry that favors inclusiveness over stylistic rigor. The generous impulse that makes the movie resemble at separate times a musical, a comedy, a western, a biopic, a biblical epic, a medieval legend, and a Dumas adventure story also results in beautifully lit, framed, and composed shots and sequences that coexist with ones that are more hastily and casually put together. It’s an overflowing smorgasbord of a movie, and one reason its echoes of old Hollywood are so appealing is that new Hollywood probably couldn’t come up with such an intoxicating mixture if it tried — industry wisdom would undoubtedly deem such a project naive and outdated.

In contrast with Destiny, just about everything in The Adopted Son is circumscribed and rigorous — even though its style is flexible enough to include one experimental, handheld sequence that wouldn’t be out of place in a Stan Brakhage work. The film cost about half a million dollars to make, and I would surmise that this means that every shot and every sound recorded on the sound track was made to count. It also suggests that Aktan Abdikalikov, like Robert Bresson (whose current retrospective at the Film Center, with new 35-millimeter prints, is one of the major local film events of the year), operates according to a principle of aesthetic economy: images are developed in relation to other images, sounds are developed in relation to other sounds, and sounds and images are developed in tandem as a way of defining and shaping one another. One can’t come away from The Adopted Son with any sense of deprivation as long as one’s expectations can be adjusted to the size of Abdikalikov’s canvas. That canvas may be small, but in more ways than one, phenomenologically as well as conceptually, some version of the entire world can be found in it. Part of the pleasure of watching this film is seeing that world reconstructed piece by piece.

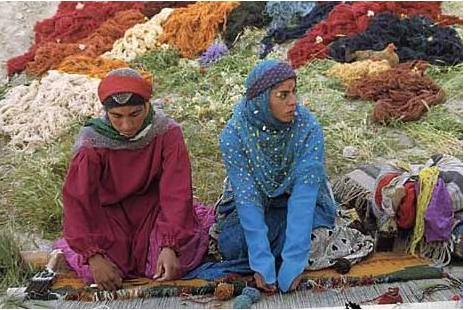

Abdikalikov’s sparing use of color — clearly a matter of aesthetic rather than financial economy — reinvents our perception of color as well as of black and white in movies: every shift between these registers is experienced as an epiphany, a bursting re-creation of the world. When Abdikalikov was asked in Locarno last summer after the first screening of his film what motivated this eccentric construction, he replied that it was inspired by the way rugs in Kyrgyzstan are woven and patched together. A lateral camera movement over one of these gorgeous rugs in color is the film’s first image, and everything that follows conforms to this beautifully abstract pattern, much the way a musical theme would be developed.

This “carpet connection” has prompted some commentators to compare The Adopted Son to Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s Iranian film Gabbeh (see below), but I think the differences between these films are more important than the similarities. The ethnographic world of Gabbeh isn’t even remotely that of the filmmaker, who’s a talented and imaginative observer, and the somewhat touristic packaging of that world was in some ways Makhmalbaf’s calculated bid to “sell” Iranian cinema in folkloric and consumerist terms to a wider market; his effort succeeded, as did the similarly distanced efforts of Abolfazl Jalili, whose Dance of Dust has been a recent favorite on the festival circuit.

But Abdikalikov’s project is to tell us something about his own life and background. His film’s original title is Beshkempir — the name traditionally given in Kyrgyzstan to a baby son passed over to a childless couple (baby girls — as in Jewish, Islamic, Chinese, and, alas, many other cultures — are considered less desirable). Abdikalikov wasn’t given that name himself, but he did undergo something of an identity crisis when he found out at 13 that his mother and father weren’t his biological parents. Part of this experience is transferred to his teenage hero, who makes a similarly traumatic discovery of his true origins when he’s ridiculed by his playmates for being adopted, then winds up fighting with them. (The film as a whole is more poetic evocation than social criticism, but the sexist brutality of Kyrgyzstan life isn’t entirely ignored: the angry mother of one of the hero’s playmates tells Beshkempir, “He’s not your wife to beat up like that.”)

This identity crisis is only one of the more colorful threads in the tapestry. Before culminating in the stately funeral of Beshkempir’s grandmother — a ritual made to rhyme with the adoption ceremony at the beginning of the film — The Adopted Son concentrates on everyday activities in the village, including the games and pranks of Beshkempir and his pals as they splash and bathe in mud, steal eggs, flee from bees, spy on women. They consolidate some of their discoveries by sculpting a nude female body out of dirt and taking turns pantomiming sex with it — until a passing herd of cattle tramples their masterpiece.

The locations are as much a part of the story as the people, and the selective sounds we hear — of birds, dogs, cows, sheep, water, wind — are as important as the images. One of the best sequences comes when Beshkempir finally gets permission from his parents to go to the movies, an outdoor screening of a Hindi musical shown a reel at a time. Abdikalikov alternates black-and-white shots of the enraptured villagers with color glimpses of the movie on the freestanding screen. I suppose this could be interpreted as a trite dialectic between the drabness of everyday village life and the colorful nature of its fantasy life, but it doesn’t come across that way at all, thanks to the way Abdikalikov articulates it, using the rich palette of his black-and-white cinematography and the musical interweavings of his editing in relation to the Hindi musical’s sound track. It made me think that Kyrgyzstan spectators are in some ways freer in their aesthetic choices than their mainstream American counterparts — maybe they don’t get quite as much broken glass as we do, but they can see musicals, and black-and-white movies in the bargain.