From the Chicago Reader (January 29, 1993). Since writing this, I’ve come to like Basic Instinct much more than I did. — J.R.

BODY OF EVIDENCE

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Uli Edel

Written by Brad Mirman

With Madonna, Willem Dafoe, Joe Mantegna, Anne Archer, Julianne Moore, Stan Shaw, Charles Hallahan, Lillian Lehman, Mark Rolston, Jeff Perry, and Jurgen Prochnow.

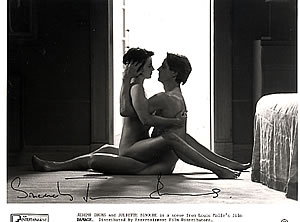

DAMAGE

* (Has redeeming facet

Directed by Louis Malle

Written by David Hare

With Jeremy Irons, Juliette Binoche, Miranda Richardson, Rupert Graves, Ian Bannen, Leslie Caron, Peter Stormare, Gemma Clark, and Julian Fellowes.

The pointed absence of scenes of sexual intercourse in such recent releases seemingly calling for them as The Crying Game, The Hours and Times, and Scent of a Woman is curious when weighed against a tendency in some other movies, including two that opened recently, to highlight transgressive or dangerous sex. In Body of Evidence it’s not only bondage and sadomasochism but sex leading to the male partner’s cardiac arrest, an effect the female partner may have intended. In Damage it’s not only illicit sex between an older, prominent government official and his son’s fiancee, who has incest in her past, but also the unconventionality of their couplings: they often remain partly clothed, and the positions they assume border on the pretzellike.

That we’re so frequently getting either baroque sex or no sex at all in movies seems partly a reflection of what AIDS is doing to people’s heads, specifically to their erotic imaginations, although it must be conceded that other factors probably come into play. In The Crying Game the absence of sex is virtually the linchpin of the narrative, though that absence is also the one factor that prevents the film from seriously dealing with the subject it purports to treat. In a more ambitious (and decidedly less commercial) effort like The Hours and Times, the lack of sex can be defended as a central part of the film’s seriousness and modesty, justified both by history (the real-life relationship between Brian Epstein and John Lennon) and by the film’s status as an “open” narrative leaving a great deal to the viewer’s imagination. In Scent of a Woman (which is much less serious than the other two, intended to do little but elicit the predigested emotions necessary to acquire Oscars), omitting the lovemaking between a blind, retired lieutenant colonel (Al Pacino) and the call girl he visits not only registers as a failure of imagination but leaves us wondering — without any benefit to the drama — whether the session was as “successful” as the lieutenant colonel claims afterward.

The handling of kinky sex in both Body of Evidence and Damage clearly harks back to certain aspects of Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1973 Last Tango in Paris and the most commercially successful of its immediate spin-offs, Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter from 1974. (It hardly seems accidental that both Body of Evidence and Damage are movies in English shot by continental European directors who’ve done kinky films before.) But in the case of Body of Evidence, these influences have been mediated by a much more recent box-office hit.

“Very Basic Instinct,” I wrote in my notes when the second scene in Body of Evidence, immediately after the credits, was barely under way. It could be argued, of course, that any movie that exposes in its first two scenes its abject dependency on another movie released only nine months earlier has to be in some kind of trouble, but only if freshness rather than box-office success is the issue. Mainstream movie reviewers long ago established that anything that makes money automatically asserts its own kind of validity — even its own kind of freshness. It’s not yet clear whether Body of Evidence is going to make money, but already the media’s prerelease cultural pricing has been determined more by guesses about its box-office yield than by any soul-searching about its originality or seriousness.

It’s easy enough to imagine how Body of Evidence sprang into being: Madonna saw Basic Instinct and said, “I wanna do one of those, too.” And though I’d generally opt for Madonna over Sharon Stone and, hands down, Willem Dafoe over Michael Douglas, and though I prefer the merely glancing homophobia in this movie to the extended lesbian baiting of its predecessor, I can’t honestly say that I enjoyed Body of Evidence more than its putative model, even if light S-M does seem a friendlier subject than linking orgasm with ice-pick murders. If I still wind up assigning a single star to Body of Evidence, which is more than I gave Basic Instinct last April, it isn’t so much because I find it more enjoyable but because I find its impulses somewhat less detestable. My rage at the stupidity of Basic Instinct’s script and the callousness of its calculations overruled any consideration I might have given it as a guilty pleasure. And although I don’t exactly agree with Manohla Dargis’s remarks on Basic Instinct in her essay on 1992 movies for the Village Voice, they still help to pinpoint virtues I failed to acknowledge in what everyone admits was a silly movie:

“From the butt-naked, uptight posturing of Michael Douglas’s cop . . . to his character’s limp dyke-baiting, rarely had masculinity seemed so ludicrous, so ill at ease. Had ever a movie this tumescent oozed this much male anxiety? Slick and overdetermined, this picture was so far out of control it got snatched by snatch. From reel one Stone owned Basic Instinct. She took it away from Douglas and made it hers, and in the process rewrote Joe Eszterhas’s misogynist tripe start to finish. It was, indeed, a performance worthy of all the great divas from Davis to Dietrich, who year in and year out turned man-made trash into gold, and yet another lesson in how complicated movies really are.”

Though Dargis engages in a bit of critical grandstanding that threatens to overwhelm what she has to say, her main point is germane. I would argue that Stone’s role in the story is at least as relevant as her performance, however, and that this role has as much to do, alas, with Paul Verhoeven’s showcasing of “Eszterhas’s misogynist tripe” — which had star billing for the heroine-villainess written all over it — as it does with Stone’s contribution. In other words, if Madonna — who apart from the sex scenes barely registers as an actress in Body of Evidence — had played Stone’s part in Basic Instinct, she would have “owned” the movie too. Regardless of its base motives, Basic Instinct gave us a powerful woman character who made its ostensible hero look like a whiny wimp, as Dargis implies, and in the long run that investment of power may have mattered as much as, or more than, the nonsense and nastiness.

Though we’ve been told that Madonna is once again “in control of her own image,” Body of Evidence doesn’t provide a female character nearly as strong as the one in Basic Instinct. And Madonna’s performance, whenever she has extended lines to deliver, is conspicuously lacking in the star power she flourishes so confidently elsewhere. The film’s press materials report that the only scenes rehearsed by director Uli Edel “before principal photography started were the several erotic episodes between Madonna’s and Willem Dafoe’s characters,” and the movie certainly looks that way. The sex scenes have the calculated, controlled dynamics of Madonna’s best videos, while the remainder of the movie — mostly flaccid courtroom drama involving the heroine’s murder trial for using her body as a weapon against a man she’s just inherited $8 million from, with Dafoe as her defense lawyer — chiefly comes across like daytime TV reruns. (The press materials understandably keep mum about Basic Instinct but are not at all reluctant to describe the murder trial as “reminiscent of the romantic intrigue contained in such courtroom movie classics from the late 1950s as Billy Wilder’s Witness for the Prosecution and Otto Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder,” politely admitting that Body of Evidence dutifully — if pointlessly — rips off both these very entertaining movies.)

The three big sex scenes all revolve around domination and actual or implied bondage. In the first two, Madonna is on top, and her main S-M tools are a lighted candle in the first session (with a bottle of wine to cool the burning wax as it singes Dafoe’s chest) and in the second the pieces of a broken light bulb against his back — on the hood of a car in a parking garage. The third scene, a much less imaginative grudge match, has him entering her from behind as she’s handcuffed to a bedpost. (Given that hot candle wax is relatively uncommon as a dominatrix’s tool in mainstream movies, it seems odd that the practice pops up in another film currently playing: Used People.)

If the choreographed sex scenes break into the pedestrian plot and dialogue of Body of Evidence like numbers in a musical comedy, that’s because they appear to be the only scenes the filmmakers really care about; otherwise the characters and story can go straight to hell, one feels, as they eventually do. A much more pervasive dullness in the upscale art movie Damage unifies the sex scenes, the dialogue scenes, and the contrived plot; they’re all in the same universe of discourse — or shall we call it the same hell of good taste? This movie might also be described as a disinterested treatment of obsession, as if these talented actors were thinking about their lunch breaks while trying to convey extreme states of passion and emotion. (There are two major exceptions: a corrosive, explosive scene with Miranda Richardson as the government official’s wife that amply proves how powerful she can be when given the part of a human being — as opposed to the monstrous bitch she’s asked to flesh out in The Crying Game — and some better-than-average scenes with Leslie Caron that suggest hidden depths in her part missing from the two leads.)

I’ve been told that it would be unfair to judge Josephine Hart’s novel on the basis of how it’s been adapted for this movie by David Hare, so I can’t assign any of the movie’s failures to its source. Similarly, I’d prefer to think that the dullness of Damage isn’t attributable to the remarkable Jeremy Irons, whom I consider an auteur — that is, a more powerful creative presence than any writer or director he works with. In this case he seems to have just honorably picked up his check because he couldn’t find anything to be creative about (unless it’s helping to arrive at the interesting positions he assumes with Juliette Binoche).

I assume that Louis Malle made this movie mainly because he wanted even more money than he already has. While there are certainly thematic links with earlier Malle films — the lovemaking in The Lovers, for instance, and the incest in Murmur of the Heart — the dutiful way he sets up the “fatal attraction” in this movie seems so calculated and so irrelevant to reality or self-expression that I suspect he may have been thinking about lunch breaks as well.