Written for the 2019 catalogue of Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. — J.R.

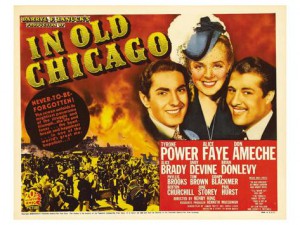

In my early teens, I wrote a time-travel yarn in which time travelers revisit 1871 to determine whether Mrs. O’Leary’s cow really kicked over a lantern that started the Great Chicago Fire — their abrupt arrival startling the cow and thereby causing the self-same catastrophe. Despite claims to being historical, this two million dollar Fox epic (1938) — a quarter of whose budget went towards depicting this fire (which had taken 300 lives and destroyed two million dollars worth of property) — seems almost as fanciful about some of its facts as I was. But Henry King, as mythical about the Midwest as Ford was about the West and De Mille was about the Middle East, makes Chicago both a cauldron of corruption (the grandfather of Ben Hecht’s Chicago) and the site of his recurring theme — the coexistence of nihilism and decency, rebellion and domesticity, represented here both by the Cain-and-Abel dialectic of the O’Leary brothers (Tyrone Power and Don Ameche) and the two women who lord it over them, a showgirl-capitalist (Alice Faye) and their prudish mother (Alice Brady), the latter of whom owns the recalcitrant cow.

Significantly, it’s the response of that cow to her obstreperous offspring that sets off the fire, just after the O’Leary boys belatedly come to blows. Hoping to top the climactic earthquake of the profitable San Francisco (1936), Fox even arranged for an intermission 80 minutes into the picture, just before the cow kicks over the lantern, getting the climactic half hour of urban blight to function like the second part of a double bill, and resolving the moral crisis with spectacle in the grand manner of D.W. Griffith.

If Chicago in this film initially figures as a Promised Land whose Moses-like father can’t enter, before it evolves into some version of Sodom and Gomorrah for his family, the same city would function years later as a tragically unreachable cultural oasis for the frustrated, Emma Bovary-like heroine of King’s Wait till the Sun Shines, Nellie (1952).

— Jonathan Rosenbaum