From Cinema Scope #19 (Summer 2004). This is obviously out of date in many respects, fourteen years later, but I repost it now a period piece. — J.R.

Joan Hawkins opens her book Cutting Edge: Art Horror and the Horrific Avant-garde (Minneapolis/London: University of Minnesota Press, 2000) with an interesting and useful observation:

“Open the pages of any horror fanzine —- Outré, Fangoria, Cinefantastique —- and you will find listings for mail-order video companies that cater to aficionados of what Jeffrey Sconce has called `para-cinema’ and trash aesthetics. Not only do these mail-order companies represent one of the fastest-growing segments of the video market, but their catalogs challenge many of our continuing assumptions about the binary opposition of prestige cinema (European art and avant-garde/experimental films) and popular culture. Certainly, they highlight an aspect of art cinema generally overlooked or repressed in cultural analysis: namely, the degree to which high culture trades on the same images, tropes, and themes that characterize low culture.”

As a direct illustration of Hawkins’ point, check out the web site www.xploitedcinema.com, a U.S. importer of overseas DVDs that also sells some domestic items and caters mainly to trash aesthetics, but among whose 86 pages of sex, horror, action, and gore items I also recently found an Italian two-disc set of my favorite Bernardo Bertolucci film, Prima della Rivoluzione/Before the Revolution (his second feature, 1964 — subtitled in English, along with all the extras), not to mention English-friendly Spanish and/or Mexican editions of my two favorite Alex Cox films (the 1987 Walker and the 1994 Highway Patrolman), a Spanish edition of Orson Welles’s Chimes at Midnight, a Korean edition of Sam Peckinpah’s scandalously underrated Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974), and Italian editions of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964, also subtitled in English) and Andy Warhol’s The Chelsea Girls (1966).

Among those I’ve received so far, I can report that the Bertolucci package includes a recent 45-minute interview with the director and shorter encounters with numerous colleagues and collaborators as well as a brief production documentary of 1964. And the Warhol box contains not only letterboxed juxtapositions of all twelve episodes (which sensibly includes each diptych twice so that we can hear the sound of each episode in turn while the adjacent one runs silent) but also a full disc of extras (including Jonas Mekas’s 1982 Scenes from the Life of Andy Warhol, a dialogue between Mekas and Paul Morrissey, and three segments of commentary by pontificating Italians —- Enrico Ghezzi, Mario Zonta, and Achille Bonitao Oliva) and an illustrated 65-page booklet in Italian and English by Silvia Baraldini and Zonta.

***

During the five years I lived in Paris (1969-1974) I never mastered French to my own or anyone else’s satisfaction, which means that I wound up seeing a lot of films without entirely understanding what was said in them. Given Henri Langlois’ philosophy at the Cinémathèque of showing many films with no translation at all, this means that I conducted much of my education in cinema without that perk. It’s something that seems worth mentioning whenever I encounter young cinephiles today who wouldn’t dream of seeing a movie whose dialogue they can’t follow, in whole or in part. While it’s obviously far better to be able to understand what you’re watching, my own education in movies would have been a paltry fraction of what it was if I’d ruled out the movies I couldn’t follow. And it’s been argued that French cinephiles seeing Hollywood films whose dialogue they couldn’t always understand in detail helped to teach them things about visual style that they otherwise might not have noticed quite as much.

All this is by way of a prelude to writing about a cluster of recommended DVDs that have no English subtitles. And since we’re already on the subject of Bertolucci, let me add that those readers who are as unsatisfied with his depictions of 1968 countercultural politics and cinephilia in The Dreamers as me —- or Richard Porton for that matter, in the previous issue of this magazine -— are urged to check out Bertolucci’s own notations on the subject in 1968 in his third feature, Partner. There you’ll not only find Pierre Clementi demonstrating his own version of how to assemble a Molotov cocktail, but also find him reading Lotte Eisner’s book on F.W. Murnau (while imitating Nosferatu, just before encountering a bit of shadow-play that evokes Faust and Sunrise), interacting with his own doppelgänger in homage to Dostoevsky, and luxuriating in the colors and satirical sight gags of Frank Tashlin in ‘Scope. At any rate, this self-indulgent but enjoyable feature, known as Il sosia in Italian, is available as Partner with French subtitles on a region 2 PAL DVD, on the French “Les Films de Ma Vie” label. And on the flip side you can see Bertolucci’s (for me less memorable) first feature, Les recrues (1962 — also known as La commare secca and The Grim Reaper), with a Pasolini screenplay.

Moving from minor to major, unsubtitled French editions on Arte Video of Hiroshima, mon amour (two discs) and Muriel (one disc), the first and third features of Alain Resnais, contain, among many other valuable bonuses, practically all his major short films apart from Night and Fog (which was recently issued separately in an excellent edition by Criterion, with subtitles), some of which for me comprise his most important neglected works. I’m thinking especially of Les statues meurent aussi (written by Chris Marker, about African sculpture, 1953) and Toute la mémoire du monde (about the Bibliothèque Nationale, 1956), which are both included with Hiroshima, and La chant du Styrène (written by Raymond Queneau, about the manufacture of plastic, in color and ‘Scope, 1958), included with Muriel —- though I hasten to add that the former DVD also contains Guernica (1950), about the Picasso painting, and the latter also contains Van Gogh (1948) and Paul Gauguin (1950), the former of which won Resnais his only Oscar to date. Another significant feature of the Hiroshima package: it contains a lovely 40-page booklet, half of whose pages are devoted to reproducing in color letters sent by Resnais along with snapshots and clippings to Marguerite Duras while she was working on the script.

(A footnote about Les statues: Marker’s beautiful text for this short — which can be found in his 1961 collection Commentaires 1, and which begins, “When men have died, they enter history. When statues have died, they enter art” —- ends with an indictment of French racism that led to the film’s final reel being banned in France for almost half a century. When this reel finally passed the censor a few years ago and the complete short turned up on French TV, this event was given some attention in Le monde, but, to the best of my knowledge, ignored in both Cahiers du Cinéma and Positif.)

Out of all the French films that I saw while living in Paris, Jacques Rivette’s Céline et Julie vont en bateau was one of the most challenging and difficult due to all its giddy word play (most of it stemming from the late Juliet Berto, the costar). And even though I was able to attend several screenings of the work print thanks to my friendship with Eduardo de Gregorio, the film’s major screenwriter, I never properly understood much of the dialogue until I saw it subtitled in London the following year. So unless your French is fluent, you’re apt to have similar problems with the untranslated two-disc set just released by Editions Montparnasse, which I recommend none the less. A second disc offers informative untranslated interviews with Rivette, all the lead actresses apart from Berto (Dominique Labourier, Bulle Ogier, and Marie-France Pisier), and Rivette critic Helène Frappat.

The transfer of the film is mainly excellent, but there are two details that baffle me. The running time given on the box is 186 minutes, six minutes less than the film has had in all its previous incarnations. And skimming through the DVD, I can only find one thing obvious that’s missing — the exit music of Jean-Marie Sénia’s piano over the concluding credits (a lamentable loss), which doesn’t alter the length of the film in any way.

On a recent visit to Paris, I was astonished to discover — in a shop near the Mabillon métro stop devoted to teaching materials for high school teachers —- DVDs which were French study guides to both Bowling for Columbine and Elephant. It’s a shop I periodically visit for its more classic DVD study guides, many of them prepared by Alain Bergala. The most impressive of these are probably those devoted to Kiarostami’s Where is the Friend’s House?, Truffaut’s Les 400 coups, Lang’s Moonfleet, and Ford’s The Searchers (a recent release), and I’m happy to say that the basic contents of the Moonfleet DVD —- a beautiful letterboxed transfer, a half-hour documentary by Bernard Eisenschitz (“The Messages of Fritz Lang: The Genesis of Moonfleet”), and a 20-minute analysis by Bergala — are now available on a French Warners DVD (region 2, PAL) with English subtitles: Look for Les Contrebandiers de Moonfleet.

***

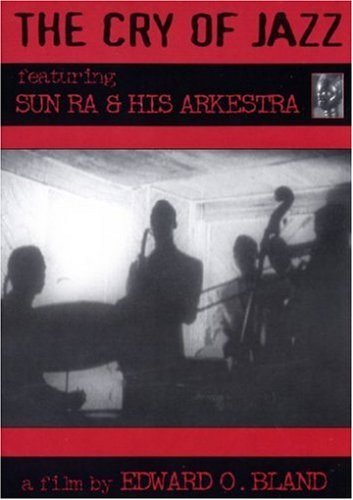

Collecting DVDs from around the world often creates a sensation of displacement. Having discovered Edward O. Bland’s Chicago-made The Cry of Jazz (1959) only recently and in Chicago —- an experience that made me realize how this singular and fascinating 35-minute film had mainly been misrepresented to me over the preceding four decades —- I’m not at all sure why I only discovered it was available on a region 0 DVD in the Virgin Megastore on Paris’s Champs d’Elysées, and not in the Virgin Megastore that I visit regularly in Chicago. Is this simply the luck of the draw, or are certain cultural differences also involved?

Similarly, I’m stumped about why a serious auteurist appreciation of Otto Preminger is more apt to come from the east side of the Atlantic, as in the BFI’s recent release of four of his early features on region 2 DVDs — Fallen Angel (1945), Whirlpool (1949), Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950), and Carmen Jones (1954), all of which, I should add, have been celebrated by Godard both as a critic and as a filmmaker (in the allusions to Dr. Korvo and Mark Dixon in Made in USA, for instance). It’s true that Carmen Jones has already been out for some time in the U.S. on 20th Century-Fox’s label. But Fox’s apparent lack of interest in either stateside editions of the noirs or in using Preminger as a brand name is surely indicative of a cultural difference. Even if I concede that the cockamamie Ben Hecht script of Whirlpool distracts at times from the mise en scène, the BFI has done such a fine job with the black and white transfers that my appetite is whetted for comparable versions of the even better Laura (1944) and Angel Face (1952).

Fortunately we no longer have quite the same problem of cultural blockage when it comes to Fritz Lang — even if we still have to go to France for our DVDs of Moonfleet and Secret Beyond the Door. After a friend recently alerted me to the wonderfully informative commentary of Lang specialist David Kalat on Image Entertainment’s double-disc set of Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1922), I was more than primed for the Kalat commentary on Criterion’s double-disc set of The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933), which also has room for the simultaneously filmed French-language version (albeit in a far less beautiful and unrestored copy) as well as diverse German documentaries or excerpts thereof. Combine this with Kino Video’s recent (and extraless) DVD of Liliom (1934) and the DVD record of Lang in French seems complete.