From Monthly Film Bulletin, December 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 503). — J.R.

Farewell, My Lovely

U.S.A., 1975

Director: Dick Richards

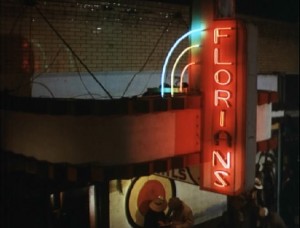

Employing the same production team (Elliott Kastner and Jerry Bick) as The Long Goodbye and the same director of photography (John A. Alonzo) as Chinatown, Farewell, My Lovely resumes the Los Angeles private-eye cycle with a clear grasp of its immediate as well as its more distant precursors. Less individual than either Altman at his most eclectic or Polanski at even his least personal, Dick Richards nevertheless seems to have an almost equally distinct idea about what to do with his material — in this case, to honor it as closely as possible in its own generic terms and not aspire to bring to it any contemporary perspective more distancing than a warm and somewhat glazed-over nostalgia. Some of the consequences — like the wonderfully evocative pastel-like impressions of L.A. at night and a torchy orchestral theme by David Shire behind the opening credits, or the deliberate use of Forties film noir devices (first person voice-over narration, flashbacks framed by blurs, dime-store expressionism to render Marlowe’s loss of consciousness — recalling Dmytryk’s treatment of the same scene thirty years ago) — are immediately apparent. In other cases, including a self- conscious series of period references (DiMaggio’s batting record, Hitler’s invasion of Russia) and recreations (the lovingly detailed and mythically idealized sets), the results are less obvious: a sentimental softening of the Marlowe character throughout is so well integrated with the crisper aspects of his fancy rhetoric that Richards and scriptwriter David Zelag Goodman almost manage to transform the detective into a Sixties liberal who plays catch Fifties-style with a grinning mulatto child without seriously jarring the reverential tone. (When he rattles on about baseball scores with his newsagent pal Georgie, however, the old-fashioned coziness begins to overflow, and one is uncomfortably reminded of some of the stickier dialogue in The Old Man and the Sea.) Equally confident is the flair for casting iconographically evocative types and pinning them like butterflies on to the shallow surfaces of this dreamy memory book: a virtually definitive Marlowe and Nulty in the tired, resonant presences of [Robert] Mitchum and [John] Ireland; a Joe Palooka comic strip suggested by Jack O’Halloran’s Moose Malloy; Charlotte Rampling carefully clothed and framed to remind one of Lauren Bacall, sufficiently fulfllling her genre-bred erotic duties in two longish scenes to justify Marlowe’s off-screen tribute, “She gave me a smile I could feel in my hip pocket”. The net results of these and comparable strategies — which include an impressionistic use of neon signs, colored lights and ‘posed’ period tableaux (making Florian’s nearly resemble a musical comedy set) — are twofold. On the one hand, they make the plot elements and characters (most of them preserved from Chandler’s novel) seem as patently old-hat as Marlowe’s faltering grasp of their counterparts in Altman’s The Long Goodbye, an endearingly exhausted repertoire of cliché stances and intrigues which register like the predictable contours of a familiar fairy-tale. On the other, they paradoxically take up the equally dated brassy precision of Chandler’s weary wisecracking prose and grant it an unlikely second life, letting its inventiveness shine and crackle through the actors’ measured inflections like a semi-abstract gibberish poetry flourishing for its own sake, inventing its own rules, and triumphantly outlasting the specific narrative circumstances, social portraits and ethical codes that it so painstakingly describes.