From the Chicago Reader (January 23, 1998). Today I would probably rank this movie much higher. — J.R.

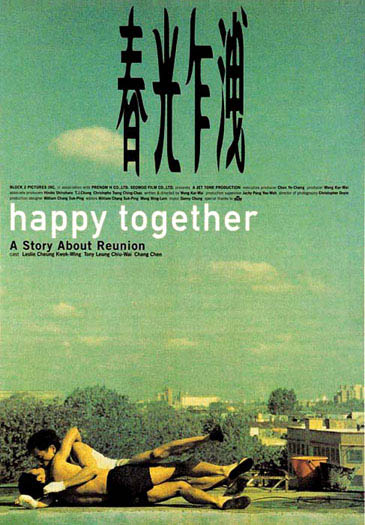

Happy Together

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed and written by Wong Kar-wai

With Tony Leung, Leslie Cheung, and Chang Chen.

At some point in the mid-90s Wong Kar-wai’s exciting and hyperbolic style lost its moorings. Whether this happened between Days of Being Wild (1990) and Chungking Express (1994), during the two years it took to make Ashes of Time (1994), or between the latter two films and Fallen Angels (1995), Wong’s powerful organic flow, which makes Days of Being Wild his only masterpiece to date, has atrophied into a slag heap of individual set pieces.

Many of these set pieces are thrilling enough in their own right. Fallen Angels has plenty of them, spaced out like showstoppers in a vaudeville revue, though their effectiveness tends to diminish, their frenetic intensity ultimately becoming monotonous. Like the mannerist tics comprising Wong’s style — the use of different characters as narrators; the momentary freeze-frames punctuating Christopher Doyle’s slowed, slurred, or speeded-up cinematography; the shifts between color and black and white; and the bumpy transitions between garish forms of lighting and visual texture — his set pieces always provide a lively surface activity. If your acquaintance with Wong’s work is casual, that may be all the justification he needs. But when Wong tries to turn these sequences into something larger, the results are more various and uneven.

It’s an issue not of subject matter but of overall method. For Happy Together (1997), Wong reduced his essential cast of characters to three and flew them halfway around the world, from Hong Kong to Buenos Aires (adding a couple of side trips to Iguacu Falls and Tierra del Fuego). The subject, moreover, is probably his boldest to date: an acrimonious and ultimately doomed gay relationship between two Hong Kong expatriates, a match that never quite becomes a triangle with a straight expatriate from Taipei. But far from concentrating or distilling his material, Wong winds up scattering it to the winds.

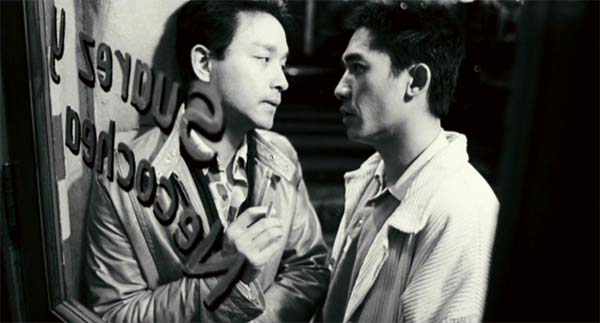

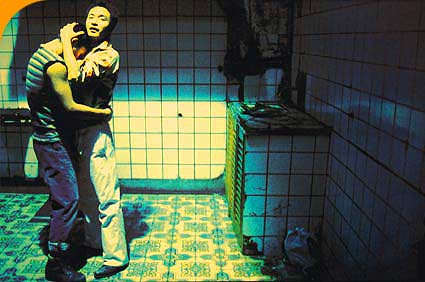

There are plenty of interesting aspects to this epileptic fresco. There’s the passionate treatment of gay sex and romance by a straight director, featuring two of the hottest stars of Hong Kong cinema (Tony Leung and Leslie Cheung, both of whom have worked with Wong before). There’s the charged and ambiguous friendship between Lai (Leung) and Chang (Chang Chen, the 14-year-old hero of Edward Yang’s 1991 film A Brighter Summer Day, who’s since become a big pop star in Taiwan). There’s an oblique but pungent response to the end of colonial rule in Hong Kong, a sense that the characters aren’t sure where or who they are as they approach the uncertainty of millennial crossover with fretful wanderlust. (A key phrase recurring in the narration and dialogue is, “We could start over.”) There’s also a sidelong glance at the way a particular subculture (Chinese) can reduce a dominant local culture (Buenos Aires) to a few pop staples: tangos and milongas by Astor Piazzolla, tunes by Frank Zappa, cigarettes, two sleazy bars, one lurid lava lamp. Ironically, what prevents Happy Together from becoming anything more than the sum of these parts is the same thing that keeps it alive: Wong Kar-wai’s cult status.

It’s not clear whether any director consciously sets out to attract a cult, but once he has one, several choices are possible. Like Quentin Tarantino — who served as distributor of Chungking Express, and who became a cult figure himself after only one feature — he can shed his skin, redirect his audience’s expectations, and alter his constituency. Tarantino’s new film Jackie Brown reconfigures him for friend and foe alike; after training his audience to expect certain things from his movies — cross-references to his previous films, his presence as an actor, jokey treatments of gore and violence, repeated use of the word “nigger,” and unorthodox treatments of narrative chronology — Tarantino made good on only the last two, and even then he shifted the rules somewhat by allowing “nigger” to be spoken only by a black character, and by repeating a narrative sequence from different viewpoints much as Stanley Kubrick had in The Killing. (A sadder example of a filmmaker disappointing expectations is George Romero, who went from being a revered cult director to a failed mainstream director and then retreated into silence.) A less calculated redirection of expectations can be found in the last two features of David Lynch – -another cult figure who became so overhyped that a critical backlash became inevitable. In contrast, cult favorites like Woody Allen and John Waters, whatever their ups and downs, usually manage to satisfy or at least placate their most ardent fans, perhaps because in their cases personality counts for more than invention.

As a cult hero, Wong Kar-wai is closer to Tarantino and Lynch than to Allen and Waters because his films are more a matter of style than personality. But his films, like Allen’s, have a particular “look” that derives from his using the same collaborators again and again — Doyle and art director William Chang — and I’m beginning to wonder if these associations, for all their benefits (such as Doyle’s wild, improvisatory style) may have also led to a creative impasse. Excerpts from a diary Doyle kept during the shooting of Happy Together, published in the May 1997 issue of Sight and Sound, repeatedly suggest this possibility, along with the certainty that Wong’s off-the-cuff method — working with an outline, a handful of music CDs, and a few images and ideas rather than a proper script — carries enormous risks. After recounting a “story breakdown” that differs in several particulars from the one Wong finally settled on, Doyle records mainly their uncertainties:

“At first we hesitated to repeat our ‘signature style’ [i.e., using in-shot speed changes in the camera], but eventually it was too frustrating not to….

“Shirley Kwan [a pop singer ultimately cut from the film] and Chang Chen have arrived to join the cast–or what we’re starting to call the ‘casualty list.’ They idle in their rooms waiting for their roles to materialize, while Wong hides in nearby coffee shops hoping for the same. We stop shooting for the umpteenth time to ‘save money,’ to ‘acclimatize our new stars.’ Now that they’re here, we fret over what to do with them, and over the thematic justifications for them even to be here….

“[After shooting at Iguacu Falls] I ask William [Chang] if this is a real or imaginary part of the film. We’re on our own again today; Wong’s still working out whether this is a flash-forward dream sequence or the last stop on [Lai’s] physical and spiritual journey and another possible ending for the film. We decide to shoot it both ways.”

To the best of my knowledge this hasn’t been remarked on in the Anglo-American press, but over the past few years we’ve seen a veritable explosion of films and videos about homosexuality and various kinds of gender-bending in the Chinese-speaking world. Starting near the present and going backward, we’ve now seen Chicago bookings of Happy Together, Yim Ho’s Kitchen, Tsai Ming-liang’s The River, Stanley Kwan’s Yang + Yin: Gender in Chinese Cinema, Tsai Ming-liang’s Vive l’amour, Shu Kei’s Hu Du Men, Ang Lee’s The Wedding Banquet, and Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine (not to mention the “straight” homoeroticism of John Woo). Whether this signifies a loosening up of censorship or a more general shift in Chinese consciousness, I can’t say, but as Kwan suggests in Yang + Yin, Chinese male sexuality is very much tied to a particular image of the father that is currently under siege — a fact directly and shockingly addressed in The River, which is partly about a father’s unacknowledged lust for his own teenage son.

Wong has stressed that Happy Together was inspired by contemporary Latin American fiction, Manuel Puig’s The Buenos Aires Affair in particular: “I was besotted with the title and always wanted to use it for one of my pictures. Then, after the shooting in Buenos Aires, I finally realized the film is really not about the city, so my long cherished title went out of the window and I needed to come up with something new.”

But the title he came up with (which alludes to the song played at the end of the picture) seems even less appropriate except as a desperate form of irony, because whatever else Lai (Leung) and Po-Wing (Cheung) are together in the movie, it isn’t happy. After some energetic lovemaking in the opening moments, it’s all downhill. First they split up en route to Iguacu Falls; then, after Lai gets hired as a tango bar doorman and Po-Wing drifts into prostitution, the latter gives the former a Rolex stolen from a client to help pay for his plane ticket back home. Lai is determined not to get involved with Po-Wing again, but after Po-Wing turns up on his doorstep severely beaten Lai takes him to the hospital and lets him stay in his one-room flat while his bandaged hands heal. They fight almost constantly, and Lai hides Po-Wing’s passport.

Things deteriorate further, professionally as well as romantically; after Po-Wing splits, Lai becomes a waiter at a Chinese restaurant (where he meets Chang), a slaughterhouse worker, and a prostitute. “I thought I was different from Po-Wing,” he muses. “It turns out that lonely people are all the same.” Chang, who will eventually have to return to Taiwan for his military service (as did actor Chang Chen after playing this part), eventually takes off for “the lighthouse at the end of the world” in Tierra del Fuego. Lai goes looking for him in Taipei the same day that Deng Xiaoping dies in Beijing–finding only a snapshot of Chang at his family’s noodle stall, which he steals.

Like its characters, Happy Together is less a film with a subject than a film about not being able to find one. At best it’s a movie about being at loose ends, though it seems to mean something more for some Chinese viewers. Asian film specialist Tony Rayns, who subtitled the film, claims that it’s “one of the most searing accounts ever made of doomed and destructive love, but also a strong and very moving affirmation of romantic folly.” Presumably Wong hopes so, if only to justify all this lurching around. For me Happy Together is more like a striking mannerist style in search of content, made poignant only by the homesickness and emotional confusion underlying the effort.