From the September 13, 1996 issue of the Chicago Reader. This film was probably the most popular of the dozen features I showed to MA students in my World Cinema Workshop at Film.Factory in Sarajevo (September 15-19, 2014). — J.R.

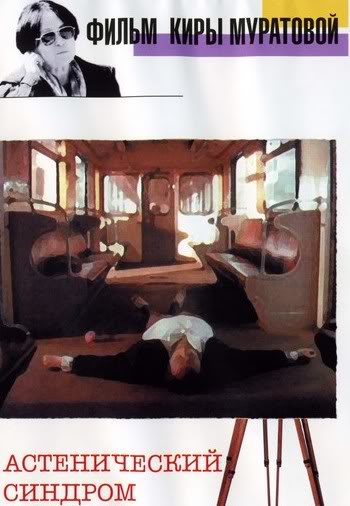

The Asthenic Syndrome

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Kira Muratova

Written by Sergei Popov, Alexander Chernych, and Muratova

With Popov, Olga Antonova, Natalya Busko, Galina Sachurdaewa, Alexandra Ovenskaya, and Natalya Rallewa.

Every time I am asked what the film is about, I reply, quite honestly, “It’s about everything.” — Kira Muratova, 1990

Seven years have passed since I first saw Kira Muratova’s awesome The Asthenic Syndrome at the Toronto film festival, and while waiting for it to find its way to Chicago I’ve had plenty of time to speculate about why a movie of such importance should be so hard for us to see. Insofar as movies function as newspapers, this one has more to say about the state of the world in the past decade than any other new film I’ve seen during the same period, though what it has to say isn’t pretty. So maybe the reason it’s entitled to only one local screening — at the Film Center this Sunday — is the movie business’s perception that it must offer only pretty pictures. Or maybe it’s the radical, sprawling form of The Asthenic Syndrome — a movie that breaks all the usual rules when it comes to telling a story and clearly distinguishing between fiction and documentary, fantasy and reality, “prose” and “poetry,” anger and detachment.

Or maybe the fact that it was directed by a Russian woman in her mid-50s — even the most celebrated living Russian woman filmmaker, which counts for little in our culture, with its relative indifference to Russian filmmaking — automatically gives it the status of an esoteric specialty item. (It’s playing as part of an excellent program, “Sisters: Films by Russian Women,” packaged by Wendy Lidell — one of this country’s key programmers, who introduced American viewers to filmmakers such as Raul Ruiz and Hou Hsiao-hsien before the collapse of government funding for the arts ended her Cutting Edge series.) After all, we’re told implicitly as well as explicitly by our cultural commissars that human experience is no longer universal: women are different from men, Russians are different from Americans, the elderly and middle-aged are different from the young, the rich are different from the poor, the educated are different from the uneducated, smokers are different from nonsmokers, Republicans are different from Democrats. Such, at any rate, is the way most products — including movies and politicians — are sold, and the way products are sold forms many of our philosophical presuppositions about what we like and who we are.

From this point of view, we might agree with Russian critic Andrei Dementyev, who declared The Asthenic Syndrome “the only masterpiece of glasnost cinema.” It’s certainly explicit about many of the horrors Russians lived through in that period — and are still living through — without being especially political or ideological in its attack, only ethical and humanist. Yet even though I’ve never been to Russia, my instincts tell me that throughout the cold war, for all the differences in the ways they lived, Russians and Americans were linked by their common subservience to the same “system” — a system that was neither communism nor capitalism but the cold war itself. And now that the cold war is over, we still seem to be sharing portions of the same destiny and life experiences, thanks to the confusions of the postcommunist aftershock and the whims of the global economy.

The central poetic vision of The Asthenic Syndrome — as relevant to America in 1996 as it was to Russia in 1989 — is that two basic, debilitating forms of compulsive behavior are loose in the world today, extreme aggressiveness and extreme passivity: either people walk down the street picking fights at random with other people, or they go to sleep at a moment’s notice, regardless of what’s happening around them. “Asthenia” is defined in the American College Dictionary as “lack or loss of strength: debility,” and some critics have given Muratova’s film an alternate English title, The Weakness Syndrome. Apparently Muratova connects the syndrome to both kinds of behavior. Both, after all, are ways of being “out of control.” It might be said that formally speaking The Asthenic Syndrome is “out of control” as well. It’s a film that alternately assaults you and nods off — usually without warning and often when you’re least expecting it. Mean-spirited and assertive one moment, narcoleptic and in complete denial the next, it bears an astonishing resemblance to the disconcerting rhythm of contemporary public life.

As the opening credits indicate, this 153-minute film is in two parts, though the second part, in color, is almost three times as long as the black-and-white first part. It begins by cutting between a few disconnected and seemingly unrelated details in the same general wasteland; a boy blows soap bubbles that drift past refuse that includes a doll and a crutch; three women chant in unison, “I believed when I was a girl that if everyone read Tolstoy, everyone would be kind and intelligent”; men inside an enormous pit tie a tin can to a cat’s tail; two other men converse nearby. Eventually a few details coalesce into a story line: the enormous pit becomes a grave site, and a middle-aged blond woman, Natasha (Olga Antonova), is burying her husband, a man whose mustache makes him look a little like Joseph Stalin; several other mourners are in attendance.

This sequence is soundless apart from music until we hear a piercing howl of grief from Natasha; then normal sound effects resume for a while. After she hears a man by the grave site laugh, she stalks away, leaving the pallbearers confused about whether they should proceed with the burial; four friends meekly follow her, intending to bring her back, but she tells them all to go to hell. She looks at other graves, then at rows of photographs outside a photographer’s shop. After lingering outside a florist’s she boards a bus, its only passenger, and for a spell the only sounds we hear are of the bus. (Throughout this sequence the isolation and fluctuation of individual sounds express perfectly her fractured, alienated consciousness.)

As she gets off the bus, a pushy and argumentative crowd gets on; she gestures defiantly at them and shortly afterward picks a fight with a stranger by saying “What’s up? Want to sleep with me, you beast?” and then slapping him. He throws her down on the ground, and a nearby woman calls her a prostitute. She lies in a heap, screaming with misery. Her four friends catch up with her again, and she continues to rebuff them.

Back in her apartment Natasha pores over numerous photographs of her late husband and herself, idly smashes a number of drinking glasses, then throws clothes out of her closet onto the floor. When a desperate neighbor with a sick wife appears at her door asking for medical help — she’s a doctor — she slams the door in his face, then goes to sleep on the floor. Later she goes to the hospital to resign her post, insulting colleagues en route, pushing people on the sidewalk outside, and going ballistic when one man tries to offer her some sympathy. Finally she invites a drunk to follow her home, orders him to undress, coaxes him into bed with her, and after a few kisses and caresses becomes hysterical and kicks him out.

This relentless black-and-white section ends abruptly in a screening room that’s shown in color, where Antonova, the actress playing Natasha, is present for a discussion with the audience. But the audience isn’t the least bit interested in a discussion and noisily gets up to leave; two members break into a fight, a child clamors for ice cream, and a man complains to his wife how depressing the whole thing was — when he goes to a movie he wants to be entertained. After several soldiers in the back rows leave, the only remaining member of the audience is Nikolai (played by Sergei Popov, one of the two writers who collaborated with Muratova on the script), a young schoolteacher and aspiring writer, the hero of the film’s second part — and he’s fast asleep. After rousing himself long enough to get on a subway, he steps off the train and dozes off again on the floor of the subway station.

The above account of the first 40-odd minutes of The Asthenic Syndrome may sound relatively linear and seamless, but I’ve had to omit a great deal to make it seem that way. And when it comes to the film’s second part, where the intrusions of everyday street life and the loopy narrative digressions are far more numerous, defining a continuous, coherent plot is even harder. Muratova’s transgressiveness functions on so many different levels that it shouldn’t be too surprising that The Asthenic Syndrome is the only Russian film to have been banned by the Soviet government during perestroika — though it wound up being shown anyway after the government sold the rights to the movie to a Moscow film club.

“I can’t authorize the release of The Asthenic Syndrome because I am against it,” declared Alexander Kamshalov, president of Goskino, the Soviet film ministry. Apparently the main objection was to a foul-mouthed monologue delivered by a middle-aged woman (not Natasha) in the final sequence — a monologue so obscene that, as a Russian acquaintance has informed me, even the fairly extreme English subtitles can’t do it justice — though some commentators have suggested that some male frontal nudity in the middle of the film may also have given offense. Whatever the reason, these two details are scarcely out of keeping with the rage, passion, caustic humor, and playful eclecticism of the movie as a whole. To remark — as a few critics have — that certain sequences are excessive is about as relevant as calling the Pacific Ocean wet; from beginning to end this movie comes at you like a tidal wave. If you only want to get your feet wet, perhaps you should stick to some safe Hollywood mush.

One thing that gets Muratova especially riled up is cruelty to animals: many characters are defined in part by their relationship to pets, and one of the most powerful documentary segments transpires in a dog pound. The movie also abounds in screaming arguments, many of them quite funny. When Nikolai insists to someone “We must educate the soul,” his interlocutor replies, “It helps to cut off hands.” A characteristic refrain in a debate among school staff while Nikolai snoozes nearby is “Eggs can’t teach hens anything; Turgenev understood.” Another refrain is the ancient American pop song “Chiquita,” sung by a crooner who sounds like Rudy Vallee — though the movie’s eccentric musical highlight has to be a solo rendition of “Strangers in the Night” performed on trumpet by a huge woman who’s the director of studies at Nikolai’s school.

The film abounds in playful confusions. Nikolai, who teaches English, has two devoted students who sit together in class and are both named Masha (Natalya Busko and Galina Sachurdaewa); both come to visit him when he winds up in a madhouse. Doubtless there are other details referring specifically to aspects of everyday postcommunist Russian life that are too local to register with much clarity to outsiders like me. Truthfully, I found the movie a lot easier to follow when I saw it a second time and knew not to look for too much plot continuity, though I can’t claim there weren’t parts that still baffled me. The movie’s a treasure chest, and if we get to see it more, more will surely become clear.

Nevertheless, the fundamental aspects of the asthenic syndrome come across loud and clear — you certainly don’t have to be Russian or postcommunist to recognize them as central philosophical as well as behavioral strains in our public life. Jonathan Schell’s reflections on the current presidential campaign in the August issue of the Atlantic provide only one recent example of corroborating evidence: He rightly notes that the American public’s current hatred for both politicians and the news media, now perceived as a single class, seems oddly out of joint with the fact that both politicians and the news media tailor what they say and do to the polls — that is, to the express wishes of the American public. Does this mean these polls are wrong? Not necessarily, because it’s the polls that also tell us that the American public hates politicians and the news media. (Whether these polls deserve to be enshrined by politicians, the media, and Schell is a separate issue.)

Maybe what this means, Schell suggests, is that the desires of the electorate are so poorly thought through that people can’t deal with having them echoed in the sound bites of politicians and newscasters, which only exposes their inadequacy. If everyone wants the budget balanced without higher taxes and brutal spending cuts — a sleight of hand no one can achieve — then any politician who promises to achieve this impossibility becomes a liar, and any politician who resists the same seduction risks a serious dip in the polls. So aggressive hatred of politicians, the media, and the federal government can be read as a displaced form of self-hatred that ultimately expresses itself in denial — both forms of the asthenic syndrome working together. And the lies we require from Hollywood movies are no different. Perhaps that’s why it’s taken seven years for a film as great as The Asthenic Syndrome to get one screening in Chicago: it tells the truth about where we are.