Chicago International Film Festival coverage, from the Chicago Reader (October 10, 2003). — J.R.

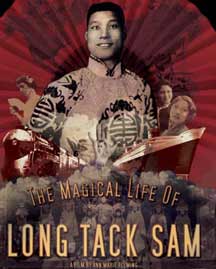

Among the films screened at the Toronto film festival last month that will turn up here eventually was Jim Jarmusch’s Coffee & Cigarettes, which taught me something about the complex ethics of celebrity — including the resentment fame can foster in noncelebrities and the defensiveness this resentment can provoke in turn. It also showed me how a cycle of comic black-and-white shorts can become a thematically and formally coherent feature. Other festival films were equally edifying, in their own ways. Ann Marie Fleming’s The Magical Life of Long Tack Sam — a playful, speculative documentary about Fleming’s once-famous great-grandfather, a Chinese stage magician who toured around the world — tells the story of his life by telling the history of the 20th century.

In The Saddest Music in the World Guy Maddin applies his hallucinatory, pretalkie visual style to a characteristically deranged script, which has hilarious things to say about how the colonialist chutzpah of big business in the U.S. looks to a cowering Canadian artist. Errol Morris’s documentary about Robert McNamara, The Fog of War, suggests, among other things, that in terms of power relations Morris is ultimately as subservient to McNamara as McNamara once was to Lyndon Johnson. Takeshi Kitano’s Zatoichi, a rousing action flick that turns into a stomping dance musical, demonstrates that it’s possible to enjoy a formulaic samurai picture. Even a boring stretch of nihilism like Dogville taught me that Lars von Trier, as Andrew Sarris once wrote about Billy Wilder, is too cynical to believe in his own cynicism.

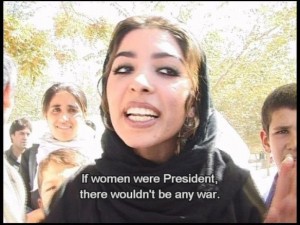

None of these features, which are all about power — especially the power of film — is screening at the Chicago International Film Festival, but as entertainment and as edification they’re easily matched by festival offerings. In previous years the festival tended to cram most of its strongest films into the first week, but this year most of my favorites are playing during the second week: a feature by Taiwanese master Tsai Ming-liang, Goodbye, Dragon Inn, and his short The Skywalk Is Gone (showing as part of “Shorts 2: Where You Stand”); Jafar Panahi’s Crimson Gold; Manoel de Oliveira’s A Talking Picture; Hakim Belabbes’s Threads; and Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Distant. There’s also a fascinating duo by the Makhmalbaf sisters: Samira’s At Five in the Afternoon is a fiction film about a young woman in post-Taliban Kabul sneaking off daily to a secular school and dreaming of becoming president of Afghanistan; Hana’s Joy of Madness is a documentary about Samira trying to cast At Five in the Afternoon (you can catch them back-to-back at the Music Box on Wednesday night, which I highly recommend).

Cinema wields power in many parts of the world, particularly in relation to powerless people, whether they’re potential viewers or potential participants in the filmmaking. This is evident in one way or another in all the films I’ve mentioned so far, as well as in many new commercial releases. (The popularity of martial arts among powerless people in Asia and elsewhere is at the root of Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill diptych, composed as a tribute to the parts of his youth spent in grind houses watching such stuff when he was powerless himself.) The threat of urban renewal in Taipei hovers over both of the Tsai films: a movie palace is about to close in Goodbye, Dragon Inn and a pedestrian bridge has already been removed in The Skywalk Is Gone. Cinema figures as a dying empire in Goodbye, Dragon Inn, a contemporary kind of ghost story; in The Skywalk Is Gone it’s our only means of perceiving the subtle consequences of urban renewal on the two lonely individuals who met on the skywalk in Tsai’s previous feature, What Time Is It There?

The barriers between the haves and the have-nots in Tehran are the subject of Crimson Gold, its action framed by a surveillance camera inside a jewelry store. Distant is a Turkish feature about the difficult interactions between a power freak in Istanbul and his country cousin; it won the best director and best actor prizes at Cannes and the “film of the year” award from the international film critics’ organization Fipresci. The power relation of an American ship captain to tourists from Mediterranean countries figures in the shocking denouement of A Talking Picture, where the various languages in which the movie dialogue is spoken play an important role. And the shifting power relations between traditional Moroccan patriarchy and American freedom are essential to the cinematic interweaving of the plot strands in Threads.

In Iran, where at least a dozen film magazines regularly appear, filmmaking allows for more upward social mobility than most other professions. Mohsen Makhmalbaf — the father of Samira and Hana and a major presence in Joy of Madness — is a rags-to-riches figure, changing from fundamentalist terrorist to outspoken progressive artist as his films grew more successful and eventually becoming a national hero and role model. The increasing intensity of the student reformist movement has led to the arrest and persecution of many Iranian filmmakers and film critics, which may help explain why the Makhmalbaf family has based all its recent filmmaking in and around Afghanistan.

Makhmalbaf filmed auditions for one of his own features almost a decade ago, turning the process into a brutal lesson about power and cinema. The resulting documentary, Salaam Cinema (1995), shows him baiting, interrogating, and at times deliberately humiliating some of the hundreds of eager aspirants who answered his ad — clearly an effort to explore why cinema grants artists the license to behave so unpleasantly. It’s fascinating that Joy of Madness shows his oldest daughter behaving in a similarly aggressive manner toward the Afghans she wants as actors in her film — though she doesn’t seem to have any broader didactic aim, apart from a desire to make a progressive film about women in Afghanistan. These potential actors are much less pliable than her father’s were, and we can easily see how the women and men she’s pursuing are far too busy with the essentials of life to be concerned with movies, either as participants or as viewers. But to Samira, hell-bent on making her progressive movie and unaware that in this part of the world cinema doesn’t count for much, their recalcitrance seems almost inexplicable — making for a good deal of high comedy.

It’s not clear whether Samira’s kid sister Hana was looking for this comedy, but I don’t think it matters much. The insights we glean from films shouldn’t be limited to the filmmakers’ intentions — or to critics’ agendas, for that matter. Seeing the interaction between Iranians and Afghans in a documentary has taught me more about both cultures than seeing the interaction between Afghans in a fiction film did, but other viewers may learn more from the art of At Five in the Afternoon than I did from the actuality of Joy of Madness. Of course, what any two viewers see as the art or the actuality of either film is bound to differ.

In addition to the films above, I can recommend Shattered Glass (which is bound to open commercially soon) and Andre Techine’s Strayed, a French film about a widow (Emmanuelle Beart) and her two children fleeing from the Nazis in the remote countryside as the Germans invade France. I haven’t caught up with Strayed yet, but Techine’s films are always worth seeing.

Screenings this year are being held through October 16 at Landmark’s Century Centre (2828 N. Clark) and the Music Box (3733 N. Southport). Single ticket prices are $6 for weekday matinees (Monday through Friday before 5 PM) and $10 for all shows after 5 PM ($8 for Cinema/Chicago members). Passes for everything but closing night are also available, good for up to two tickets per screening; they cost $50 (six tickets, seven for Cinema/Chicago members), $110 (16 tickets, 18 for Cinema/Chicago members), or $250 (50 tickets). The special presentations, which include critic’s choice programs, are $15 ($13 for Cinema/Chicago members). Tickets can be purchased at theater box offices at least one hour before the screening; they can also be bought in advance (Cinema/ Chicago, 32 W. Randolph, suite 600; Borders, 2817 N. Clark and 830 N. Michigan), by fax (312-425-0944), or by phone (312-332-3456; Ticketmaster, 312-902-1500). For more information call 312-332-3456 or see www.chicagofilmfestival.com. To access these listings online go to chicagoreader.com.