From Monthly Film Bulletin, July 1975 (vol. 42, no. 498). –- J.R.

Ghost Story

Great Britain, 1974

Director: Stephen Weeks

England; 1930. Talbot and Duller, former schoolmates of

McFayden, are summoned by the latter to a country house

supposedly belonging to a friend of his father for a weekend

of grouse hunting. Ragged and isolated by the other two for

his callow enthusiasm, Talbot is puzzled to find a warm

teacup and an odd-looking doll in his bedroom. In the

morning, he witnesses a scene in the parlor enacted by

people living forty years ago: Robert Quickworth signing

his sister Sophy over to Dr. Borden’s insane asylum, despite

the protests of her maid. At first Talbot assumes this to be

an elaborate practical joke, but after seeing people who

resemble these characters in the village pub and

dreaming or half-dreaming further episodes — in which

the doll leads him to Borden’s asylum -– he becomes

increasingly obsessed with the intrigue. Meanwhile

Duller, who has come to the house to seek ghosts with

‘scientific’ equipment, is disgruntled when all his

experiments fail and he insists on leaving. McFayden

confesses to Talbot that he has recently inherited the

house and invited him and Duller there to ‘test’ it

for ghosts, mentioning a cousin of his father’s who

went mad there. Read more

From the March 15, 2002 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

While not really a success, Nicholas Ray’s 1956 film about urban Gypsies, made between two of his near-masterpieces (Rebel Without a Cause and Bigger Than Life), has its share of interesting moments and vibrant energies, many of them tied to Ray’s abiding interest in the folkloric. In some respects this color ‘Scope feature comes closer than any of his other movies to the musical that Ray always dreamed of making: there’s a defiant dance on the street performed by Cornel Wilde, a dynamic whip dance between Wilde and Jane Russell that’s even more kinetic, and a Gypsy chorus that figures in other parts. Definitely one of the more intriguing and neglected of Ray’s second-degree efforts. 85 min. A 35-millimeter ‘Scope print will be shown. Gene Siskel Film Center, 164 N. State, Sunday, March 17, 6:00, 312-846-2800.

Read more

Read more

Like my essay on Dreyer’s Day of Wrath, this essay was written for an Australian DVD, which came out in 2008 on the Madman label. (One can order these and many other DVDs, incidentally, from Madman’s site.) My thanks to Alexander Strang for giving me permission to reprint this. (It’s also reprinted in my most recent collection, Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia. —J.R.

Mise en Scène as Miracle in Dreyer’s Ordet

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Ordet (The Word, 1955) was the first film by Carl Dreyer I ever saw. And the first time I saw it, at age 18, it infuriated me, possibly more than any other film has, before or since. Be forewarned that spoilers are forthcoming if you want to know why.

The setting and circumstances were unusual. I saw a 16-millimeter print at a radical, integrated, co-ed camp for activists in Monteagle, Tennessee — partially staffed by Freedom Riders, during the late summer of 1961, when we were all singing “We Shall Overcome” repeatedly every day. So the fact that Ordet has a lot to do with what looked like a primitive form of Christianity — combined with the particular inflections brought by the black church to the Civil Rights Movement, including one of its appropriated hymns — had a great deal to do with my rage. Read more

This is radically different from Olivier Assayas’s two previous features (Late August, Early September and Les destinees), but it suggests a continuation of his Irma Vep (1996) in its narrative ambiguity and its feeling for contemporary conspiracy. The main difference is that Assayas seems more deliberate now in tapping his unconscious, making the aura of mystery somewhat more willful. This begins as a sleek paranoid thriller about a multinational conglomerate, dominated by women (Connie Nielsen, Chloe Sevigny, Gina Gershon), that traffics in 3-D manga porn, and though the backdrop shifts from Tokyo to Paris to rural Texas, the film ultimately slides into a netherworld where it’s impossible to distinguish fact from fantasy. It’s gripping and provocative, making effective use of actor Charles Berling and the music of Sonic Youth, though I wish it were a little less indebted to David Cronenberg’s Videodrome. In English and subtitled French. 128 min. Landmark’s Century Centre.

Read more

Read more

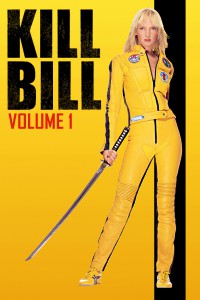

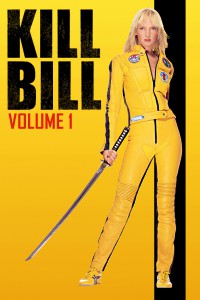

From the Chicago Reader (October 10, 2003). — J.R.

Quentin Tarantino’s lively and show-offy 2003 tribute to the Asian martial-arts flicks, bloody anime, and spaghetti westerns he soaked up as a teenager is even more gory and adolescent than its models, which explains both the fun and the unpleasantness of this globe-trotting romp. It’s split into two parts, and I assume the idea of volumes reflects the mind-set of a former video-store clerk who thinks in terms of shelf life. This is essentially 111 minutes of mayhem, with hyperbolic revenge plots and phallic Amazonian women behaving like nine-year-old boys; the dialogue, less spiky than usual, uses bitch as often as his earlier films used nigger, and most of the stereotypes are now Asian rather than black. If Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog was a response of sorts to Tarantino, then Tarantino returns the compliment here with RZA’s music and the mixture of Japanese and Italian genre elements. With Uma Thurman, Lucy Liu, Sonny Chiba, Daryl Hannah, Julie Dreyfuss, and Chiaki Kuriyama. R. (JR)

Read more

Read more

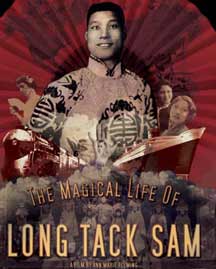

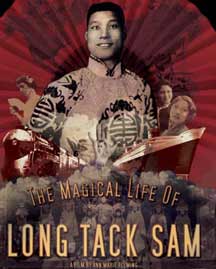

Chicago International Film Festival coverage, from the Chicago Reader (October 10, 2003). — J.R.

Among the films screened at the Toronto film festival last month that will turn up here eventually was Jim Jarmusch’s Coffee & Cigarettes, which taught me something about the complex ethics of celebrity — including the resentment fame can foster in noncelebrities and the defensiveness this resentment can provoke in turn. It also showed me how a cycle of comic black-and-white shorts can become a thematically and formally coherent feature. Other festival films were equally edifying, in their own ways. Ann Marie Fleming’s The Magical Life of Long Tack Sam — a playful, speculative documentary about Fleming’s once-famous great-grandfather, a Chinese stage magician who toured around the world — tells the story of his life by telling the history of the 20th century.

In The Saddest Music in the World Guy Maddin applies his hallucinatory, pretalkie visual style to a characteristically deranged script, which has hilarious things to say about how the colonialist chutzpah of big business in the U.S. looks to a cowering Canadian artist. Errol Morris’s documentary about Robert McNamara, The Fog of War, suggests, among other things, that in terms of power relations Morris is ultimately as subservient to McNamara as McNamara once was to Lyndon Johnson. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 3, 2003). — J.R.

A friend of a friend recently visited an uncle who’d just come back from fighting in Iraq. He conceded that the invasion hadn’t reduced the threat of terrorism or uncovered any weapons of mass destruction or exposed any links between September 11 and Saddam Hussein. “Just the same,” he said, “September 11 happened almost two years ago — and somebody’s got to pay.”

I was reminded of his words a couple days later at the Toronto film festival, when I saw Gus Van Sant’s Elephant — a fiction film about the 1999 killings at Columbine High School. No one has been able to adequately explain that massacre, and Van Sant doesn’t even try. Yet one of the teenagers’ motives may well have been “somebody’s got to pay.”

Elephant is Van Sant’s first decent film in years, but it made Variety‘s Todd McCarthy so indignant when it premiered at Cannes this past spring that his anger may have been the biggest news at that festival. This is less peculiar than it sounds, since the Cannes festival is held mainly for the press — unlike the Chicago festival, which is held for the public, or the Toronto festival, which is held for the press, the industry, and the public — and that creates an overheated critical climate where all the competing films are commonly declared either wonderful or terrible. Read more

From the Winter 1972–1973 Sight and Sound. — J.R.

REPORTER: Who are your favorite characters in the movie?

BUÑUEL: The cockroaches.

— from an interview in Newsweek

“Once upon a time . . .” begins UN CHIEN ANDALOU, in mockery of a narrative form that it seeks to obliterate, and from this title onward, Buñuel’s cinema largely comprises a search for an alternative form to contain his passions. After dispensing with plot entirely in UN CHIEN ANDALOU, L’AGE D’OR, and LAS HURDES, his first three films, and remaining inactive as a director for the next fifteen years (1932–1947), Buñuel has been wrestling ever since with the problem of reconciling his surrealistic and anarchistic reflexes to the logic of story lines. How does a sworn enemy of the bourgeoisie keep his identity while devoting himself to bourgeois forms in a bourgeois industry? Either by subverting these forms or by trying to adjust them to his own purposes; and much of the tension in Buñuel’s work has come from the play between these two possibilities.

Buñuel can always tell a tale when he wants to, but the better part of his brilliance lies elsewhere. Read more