From The Guardian, August 27, 2004, where this appeared under the title “Independence Day”. — J.R.

It’s an enduring and endearing paradox of Jim Jarmusch’s art as a writer-director that even though it may initially come across as a triumph of style over content, it arguably turns out to be a victory of content over style. The humanism of this mannerist winds up counting for more than all his stylistic tics, thus implying that his manner may simply be the shortest distance between two points.

Maybe it’s the ultimate paradox of minimalism: the less your work does and is, the more these things matter. In Jarmusch’s case, this partially means that the very notions of hipness and independence that originally defined his stylish filmmaking in the 80s — with Permanent Vacation (1980), Stranger Than Paradise (1984) Down by Law (1986), and Mystery Train (1989) — started working against his public profile in the 90s, especially once being outside the mainstream started being regarded with greater suspicion.

Furthermore, around the time of Jarmusch’s Night on Earth (1992), released the same year as Reservoir Dogs, hipness and independence as values within American culture had both become somewhat muddled and coarsened in the process of becoming mainstreamed. By then they were being used as advertising labels, and often deceptively. All of a sudden, thanks to Quentin Tarantino, being hip meant knowing all sorts of arcane facts about routine TV shows and Hong Kong action movies —- a kind of pop one-upmanship that became all the more universal by virtue of being so democratic — while being independent meant allowing Miramax’s Harvey Weinstein to decide what to cut from your own films.

The crux of the matter, helped along by corporate takeovers, was that niche markets existed only through the good graces of the mainstream, so that the Mecca of “independent” filmmaking became a festival launched by a movie star and kept vital by Hollywood agents. Just as scoring at Sundance meant getting picked up and promoted by a studio, flourishing as an “independent” meant getting distributed by Disney.

In contradistinction to Tarantino, Jarmusch still owns the negatives of his features — with the exception of The Year of The Horse (1997), a documentary about Crazy Horse commissioned by Neil Young. Furthermore, after cutting a distribution deal with Miramax for his black and white western Dead Man (1995), he didn’t allow Weinstein to make any changes — and suffered as a consequence when he saw his most ambitious film spitefully marginalized by its own distributor.

But of course the film’s mixed reception in the U.S. also had something to do with its radical content. Its unforgiving, violent look at American greed and genocide was startling in its intensity, especially after the relatively laid-back charm of his previous features. A more politically oriented Jarmusch manner was taking shape, and it has continued in Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (2000) and now, even more unexpectedly, in Coffee and Cigarettes (2003).

The first of these — which might be read as a kind of indirect gentlemanly response to Tarantino -— fancifully offers as its title hero a solitary black samurai (Forest Whitaker) in one of the New York boroughs, employed as a hitman by aging small-time Italian gangsters. The second is a collection of eleven comic sketches in black and white — all set in various American coffeehouses and adhering to certain minimalist rules of editing, camera angles, and décor (e.g., cuts to overhead shots of a circular checkerboard tabletop in each episode) — that Jarmusch started working on in 1986.

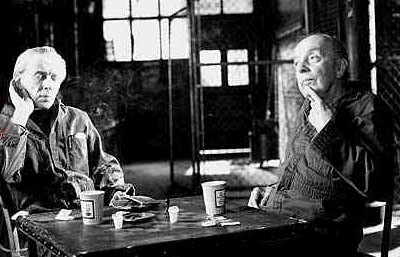

Having had the privilege of knowing Jarmusch as a friend for over two decades, I can vouch for the fact that his increasing drift towards content wasn’t intentional. It’s a conscious tribute to his roots in New York minimalism that he cast two members of that downtown scene in the final episode of Coffee and Cigarettes — Taylor Mead and Bill Rice, Beckett-like lowlifes who played, often together, in underground films by Scott and Beth B, Robert Frank, Eric Mitchell, Amos Poe, and Andy Warhol. But his wry observations about the ethics of celebrity in two other episodes —- one with Steve Coogan and Alfred Molina playing themselves, the other with Cate Blanchett playing both herself and her (fictional) resentful punk cousin Shelly in a beautifully executed split screen — are clearly more intuitive and less inherited. They derive from Jarmusch’s own ambivalence about being a recognizable underground figure in his own right, someone who can hardly walk a block in any major capital of the world without being spotted. And they both speak volumes about the perverse processes of celebrity pecking orders across the planet.

I don’t mean to imply that ethical concerns are absent from Jarmusch’s first five features —- only that they tend more often to take a back seat to the behavioral comedy. It’s worth adding that in Stranger Than Paradise and Down by Law, the two films that established his reputation, this comedy often arose from unassimilated Europeans — Ezster Balint and Roberto Benigni, respectively —- wandering with a couple of Americans through shifting black and white American landscapes that obstinately remained the same. The various cultural differences and mutual misunderstandings between the Europeans and Americans produced much of the dry humour, and Jarmusch was similarly fascinated with the spectacle of Japanese, Italian, and English characters all converging in Memphis in Mystery Train.

By the time he got to Dead Man, Jarmusch was discovering the same sort of cultural clashes between different kinds of Americans —- specifically between a Cleveland accountant named William Blake (Johnny Depp) and a maverick Native American named Nobody (Gary Farmer). Comparable clashes abound in Ghost Dog, where the black samurai hitman and a black Haitian ice cream vendor (Isaach de Bankolé) can be best friends even though they can’t speak a word of each another’s language. It should also be noted that certain fantasy elements in Jarmusch’s universe were by this time becoming more pronounced, partly because his use of Hollywood genres — westerns and hitman thrillers — were only emphasizing his distance from certain mainstream assumptions.

One of the darker implications emerging from all this was that you don’t even have to be an immigrant in America in order to feel estranged from the general populace; tribal and cultural differences are already more than enough —- even though they can sometimes be transcended by personal bonds. (One of the more touching aspects of Ghost Dog is the way the title hero can share books and reading tastes, including Rashomon and Frankenstein, with a white gangster’s moll and a black teenage girl.) More recently, this has been made apparent by the parallel outsized commercial successes in the U.S. of The Passion of the Christ and Fahrenheit 9/11 — both speaking directly to huge and mainly separate segments of the American populace that feel disenfranchised, and both made even more appealing by the scorn heaped on them in the mainstream media.

I’m reminded of Harold Rosenberg’s prescient observation about American life in The Tradition of the New (1959): “Can it be that everybody is looking for a way to fit in? If so, doesn’t that imply that nobody fits?…Perhaps it is not possible to fit into American Life. American Life is a billboard; individual life in the U.S. includes something nameless that takes place in the weeds behind it.” In a Jarmusch film, one might say that weeds are always the natural habitat.

A friend of mine who’s been teaching film production in Chicago since the 80s assures me that Jarmusch has almost invariably been the favourite filmmaker of her Third World students, not Tarantino. I was reminded of this earlier this month when Thai filmmaker Pen-Ek Ratanaruang (Last Life in the Universe) told Sukhdev Sandhu in the Telegraph how, when he was living in New York, Stranger Than Paradise came as a major revelation, introducing him “to another kind of mentality and taste; a taste very natural to me but which I didn’t know.”

I suspect this helps to account for the unexpected commercial success in the U.S. of Coffee and Cigarettes —- not a success on the level of a Kill Bill, a Fahrenheit 9/11, or a Passion of the Christ, but on the more modest level of a genuine independent like Jarmusch who wants to speak from the margins. Yet the fact that he’s about to shoot a new feature in color with Bill Murray and other prominent stars also suggests that he’s willing to push the limits of those margins.