From the Chicago Reader (May 22, 1992). — J.R.

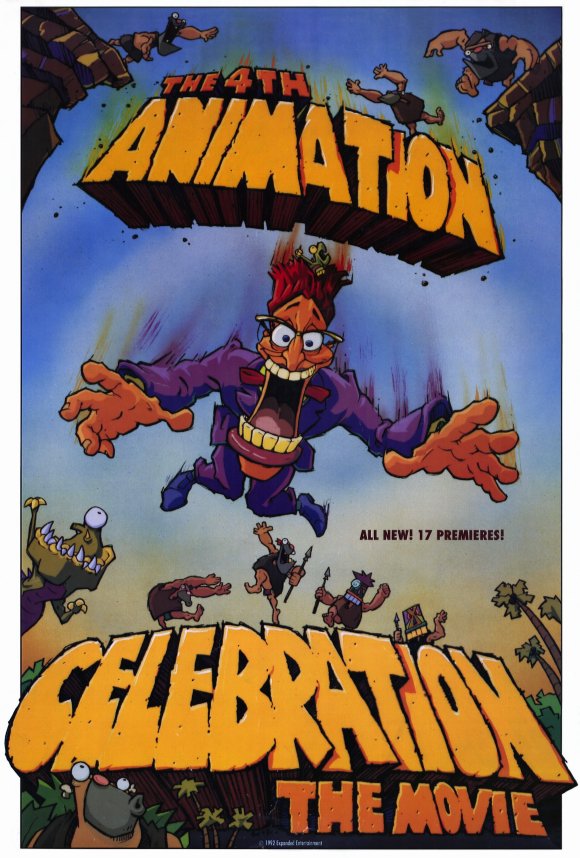

THE 4TH ANIMATION CELEBRATION: THE MOVIE

*** (A must-see)

Finding out what’s happening in the world these days is no easy matter. Turn to a newspaper and we may learn what American business wants to know — or thinks it wants to know — but not much else; check out what’s on TV and chances are that the state of the world will get less attention than the current Hollywood releases. Even when there is expanded coverage we often can’t be sure that the journalists understand what they’re reporting or that what they’re saying encompasses all that they understand.

I suppose this has always been true to some extent, and maybe it only seems worse nowadays because we no longer have newsreels. Recently some fascinating “March of Time” shorts have come out on video — newsreel “essays” produced by Time-Life and released in movie theaters by Twentieth Century-Fox in the 30s, 40s, and 50s. What seems most quaint and touching about them is how easily people (both famous and ordinary) were induced by the camera to play fictional versions of themselves that they and everyone else were persuaded to think of as real. This is the real information that these shorts impart today about their times: that the artifice was considered necessary and that no one seemed aware of it.

So much for the artifice then; what about the artifice today? At the Blockbuster on Division at Clark, “The March of Time” videos are shelved in a section called “biography,” even though these shorts have nothing to do with biography. When I complained about this to the manager, he replied that this classification system was in force nationally at Blockbuster outlets and couldn’t be changed or even questioned. Perhaps someone with the help of a computer decided that “documentary” is a term that doesn’t attract video rentals while “biography” does, and that for this reason, regardless of what these terms used to mean, they now mean something else, at least at Blockbuster.

When it comes to news in the world of film, the most disturbing thing I’ve heard lately would never turn up on Entertainment Tonight, though it’s of more consequence than anything else I’ve heard in quite some time. A teacher friend who recently wanted to have a film shown to her class discovered that a working projector might not be available, so she had a video copy booked as well. After her class saw the film she met with them and asked whether they had seen the movie on film or on video and no one in the class could tell her.

When it comes to new movies, some releases bring us news about what’s happening in the world and some don’t. When a movie that’s genuinely truthful and outspoken about current events comes along, audiences may be hip to what it’s saying (as they appear to be about Deep Cover) or not (in the case of Pump Up the Volume two years ago). But it’s fairly certain that most reviewers won’t even acknowledge that a movie is political, much less take a position on its politics. They are, however, more likely to show antipathy toward it because it’s political, though they’ll probably only speak of its effectiveness in relation to genre. In other words, they’ll be concerned with the effectiveness (read: entertainment value) of Deep Cover as a drug thriller, not with what it has to say about George Bush, the “war on drugs,” and crack babies. (If enough people outside the ghettos get the message, they might want to see the picture, too, and then the local chains might even get around to showing it at Water Tower or Webster Place — but don’t hold your breath.)

So much for the best analysis I’ve heard recently about Bush’s participation in the creation of crack babies. The best newsreel I’ve seen recently with news of the world is The 4th Animation Celebration, an 88-minute collection of 27 animated shorts from 11 countries. (One of these countries is the USSR, which for the sake of argument we’ll pretend continues to exist.) All these shorts have been made in the last five years, and if you want to know something about what people are thinking nowadays in Armenia, Bulgaria, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, or the United Kingdom, The 4th Animation Celebration: The Movie is an excellent place to start. Considering how long it takes for most foreign features to reach Chicago (first they have to survive a New York opening, often a year or more after a festival premiere), most of the cartoons here are relatively up-to-date.

The biggest problem with seeing 27 shorts in a row is that you have to keep switching gears. I found that some shorts sailed right past me because I was still stewing over the preceding ones. If you’re having trouble reading this review because of all the stopping and starting, consider how much harder it would be if each paragraph were written by someone from a different country on a completely different subject and in a different style, and you weren’t allowed to pause between them or read them at your own speed. That’s what The 4th Animation Celebration: The Movie was like to watch, but I enjoyed it a lot just the same.

In case you’re curious, as I was, how “animation celebrations” differ from “international tournees,” the press book for The 4th Animation Celebration has this to say on the subject: “‘Tournees’ are a survey of current animation trends with a global focus. The selection team is especially attentive to technical innovation and films breaking new ground in content. ‘Animation celebrations’ are made up of fun films, crowd pleasers drawn heavily from the Los Angeles International Animation Celebration, the U.S.’s only major international animation festival.” On the basis of this distinction, I would guess that “crowd pleasers” make better newsreels than surveys of “current animation trends.” (Some of the publicity for this package adds France and China to the list of countries, even though there is no short from either country in the program. Could this be because it was determined statistically by someone with the help of a computer that more people would go to see The 4th Animation Celebration: The Movie if French and Chinese shorts were mentioned in the publicity? Or is it simply a computer error?)

Phil Denslow’s Madcap (USA, 1991), which leads off the program, is a two-minute onslaught of messy abstract doodles drawn directly onto film, accompanied by music and periodically interrupted by various titles sarcastically alluding to some of the legal questions art is currently subjected to, particularly in relation to government grants or national distribution. Last month as a juror at the Ann Arbor film festival I voted against giving Madcap a prize (although it won one anyway) because both the animation and the titles seemed obvious and facile. This month, working as a reviewer and not as a juror, I think Madcap has value nonetheless as a news story about what’s happening to the arts in this country.

Zlatin Radev’s pixilated Canfilm (1990) from Bulgaria is a brilliant, often hilarious political allegory about tin cans that live in cartons resembling skyscrapers and are periodically relabeled by the powers that be. Posters and flags suddenly go up replacing cherries with tomatoes at the same time that new labels appear; can openers stretch across a prison wall like instruments of torture; later, pepper cans are arrested, and the lemons that take over wind up getting painted tomato red. The richness and intricacy of Radev’s inventive 18 minutes, scarcely even hinted at here, probably say more about what it must feel like to live in Eastern Europe in the 90s than three months of Time or Newsweek could.

Another poetic and allegorical look at apocalyptic, postcommunist political upheaval comes three shorts later in Robert Sahaguian’s The Button (1989) from Armenia, in which a man who wakes up to industrial explosions quickly discovers that every time he touches a button or anything resembling one — light switch, elevator button, touch-tone phone, prostitute’s nipple — another part of his world is demolished.

The program, which for all I know was put into order by a computer, includes two clusters of shorts that appear as self-contained units. (If each cluster counts as one cartoon, the total number of sections in the program is only 16, the same as in this review.)

The first of these clusters contains the ten winners of a contest sponsored jointly by MTV and MTV Europe and is entitled “World Problems? World Solutions!” Each film is 10 to 30 seconds long, and collectively they run for seven minutes and 45 seconds. The countries represented are Czechoslovakia (two films), Hungary, the Netherlands, the UK, and the U.S. (five films), and the issues they address, each in roughly the time it takes you to sneeze, include racism, AIDS, literacy, pollution, energy, peace, and recycling. Personally, I think all of these shorts — some of which are brilliant — belong to only one country, MTV, and seriously address only one world problem, MTV, which happens to be a lot more accepting of exclamation points than question marks. (A similar if meatier packaging concept yielded a 1990 Belgian feature called How Are the Kids?, with half a dozen nine-minute sketches about the rights of kids as defined by a UN charter of the same year. Lino Brocka, Jean-Luc Godard, Jerry Lewis, and Euzhan Palcy were among the directors, with Lewis providing the best film in the lot — though no one seems the slightest bit interested in showing the results in the U.S.)

The second cluster of shorts, which is far more successful, consists of three commissioned films conceived as personalized, contemporary homages to the great Hollywood animator of the 40s and 50s, Tex Avery — John Schnall’s Unsavory Avery (USA, 1991), Paul de Nooijer’s RRRINGG! (Netherlands, 1992), and Gavrilo Gnatovich’s Pre-Hysterical Daze (USA, 1991). The operative word here is “personalized”: like French jazz pianist Martial Solal’s 1968 live solo track “Hommage a Tex Avery,” this runs the mad master’s incongruities through thematic and stylistic changes much different from his own, although, to be fair, the traces of Avery in the work of Schnall, de Nooijer, and Gnatovich are much more recognizable. (Solal’s title may have just been a form of prescient name-dropping: Droopy T-shirts derived from Avery’s beloved basset hound became a staple on the streets of Paris by the early 70s.) Schnall seizes on the libido let loose by a torchy nightclub singer in sex-crazed Avery masterworks like Little Rural Riding Hood (1949), but reverses the sexes so that now it’s a lady who palpitates to the croon of a literal wolf. De Nooijer, working with live actors and loony sets, routes his memories of Avery-style violence through Pee-wee’s Playhouse, letting the sexual chips fall ambiguously where they may. In the most encyclopedic but least contemporary of the tributes, Gnatovich takes on a non-Averyish subject — dinosaur chases caveman — but plays with all the deconstructive high jinks that are Avery’s stock in trade: frame lines, the shadows of film spectators, separate takes, animation splices, post-end-title action.

I’m not sure that all the shorts in this program necessarily qualify as “newsreels,” or that if they do the way they do is always easy to figure out. Neat little character sketches like Candy Guard’s Fantastic Person (1991), from the UK, and Mike Judge’s Office Space (1991), from the U.S., certainly qualify because their humor is based on recognition and because the characters they describe seem especially typical of their respective cultures. But I’m less sure about the metaphysical allegory of Bruno Bozzetto’s Dancing (1991), from Italy, or the somewhat facetious The Song of Wolfgang the Intrepid–The Glorious Destroyer of Dragons (1992), by Mikhail Tumelya, from the USSR. And I’m only slightly less stumped when it comes to the wild surrealism of Stephen Hillenburg’s weird and wonderful The Green Beret (USA, 1991), which has something pretty creepy and contemporary to say about patriotism, Vietnam, couch potatoes, Girl Scouts, and imminent apocalypse, though I’m not sure exactly what. It may be that Hillenburg is deliberately trying to confound us so he can sneak certain notions past the PC thought police, much as the current, highly accomplished Australian feature Proof does. (A friend suggests that Proof raises the usually taboo specter of gay male misogyny but gets away with it because it happens to be written and directed by a woman.)

Why do some cartoons work so well as newsreels? One reason may be the time frame in which they’re created. I would imagine that the distance between thought and deed is often much greater for an animator than it is for a live-action screenwriter or director — that ideas have to be patiently developed over a longer period of time. Though this suggests that the ideas in cartoons are “older,” it may also mean that they have more mass. Cartoons’ slow, iceberglike formation may lead to iceberglike structure, where most of the newsreel material is underwater but no less present.