From The Movie, Chapter 33 (1980). -– J.R.

It was in 1940 that a brisk, buck-toothed city rabbit first sank teeth into carrot. briefly paused, gazed with indifferent aplomb at a lisping country rabbit-hunter with a shotgun and coolly inquired: ‘What’s up, Doc?’ This official debut of Bugs Bunny occurred at the beginning of A Wild Hare, one of nine cartoons that were supervised that year by Fred (known as ‘Tex’) Avery, a brilliant animator from Dallas who was working for Warner Brothers. The cartoon won an Academy Award nomination and the durable comedy team of Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd promptly went into business.

‘That darn wabbit!’

Bugs Bunny, first seen in Porky’s Hare Hunt (1938), had a complicated cross-bred genealogy. Remembering the ‘What’s up, Doc?’ expression from his high-school days in Texas, Avery had decided to place it in the mouth of a sharp Brooklynese rabbit who knew everything. Avery later recalled in an interview:

‘So when we hit on the rabbit we decided he was going to be a smart-aleck rabbit, but casual about it, and I think the opening line in the first one was, “Eh, what’s up, Doc?,’ And gee, it floored ’em! They expected the rabbit to scream, or anything but make a casual remark — here’s a guy with a gun in his face! It got such a laugh that we said, “Boy, we’ll do that every chance we get.” It became a series of “What’s up, Docs?” ‘

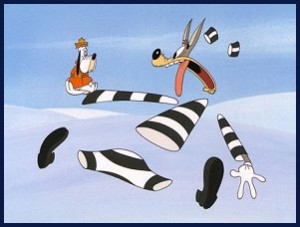

Avery’s account neatly illustrates a principle of comic dynamics underlying much of the anarchism and violence in Hollywood cartoons. The formal function of cool understatement in relation to comic mayhem is surprise and contrast — and part of the special talent of a madcap, colloquial animator like Avery lies in establishing calm centers in the midst of slapstick hurricanes. This is rather like what Buster Keaton did in live-action films during the silent era when he used his own imperturbable poker-face to provide a foil to the tumultuous world he often encountered.Bugs Bunny with his cool ‘What’s up, Doc?’ was arguably the first major exponent of this principle in cartoons. But he had many followers; not just other Avery creations, like the memorable basset hound Droopy (born at MGM in 1941), but equally nonplussed figures such as the Road Runner and The Pink Panther, who were created by fellow animators.

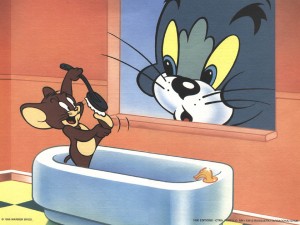

Cat and mouse games

A related principle in cartoon dynamics is the way that certain long-term antagonists are initially conceived as functions of one another, so that Bugs without Elmer Fudd (or an equivalent enemy) is like a cart without a horse. This certainly seems to have been the case with the creation of Tom and ]erry in Puss Gets the Boot (1941), an MGM cartoon produced by Rudolf Ising (whose cartoon character Little Cheeser was a forerunner of Jerry) and jointly directed, without credit, by newcomers William Hanna and Joseph Barbera. Although in this effort Tom went under the name of Jasper and Jerry had not yet acquired a name of any sort, the essential rules and conditions of their sadomasochistic relationship were already clearly established.

Tom is ordered by Mammy Two-Shoes, the stereotyped black maid always seen from the viewpoint of cat and mouse and never glimpsed above her apron, to catch Jerry and suffers cruel, brutal and protracted punishment as a consequence (which leads in turn to him getting the boot from Mammy). He undergoes a series of horrific tortures that were to grow more complex and graphic over the years as the pace of the cartoons quickened and the salient facial expressions of cat and mouse became better defined. It would be misleading to call Tom and ]erry the cartoon equivalents of the Three Stooges, yet it does seem evident that the proportion of sheer physical pain endured in their respective shorts, compared to that in other types of comedy, gives them a similar association in the public mind — an association of slapstick with ill-tempered aggressiveness and violent physical abuse.

In all fairness to both sides in the long debate about the nature of cartoon violence, a remark made by Pete Burness, a participant in a 1963 press conference with animator Chuck ]ones, bears repeating:

‘In the American cartoon, death, human defeat, is never presented without being followed by resurrection, transfiguration. A cartoon character can very easily be crushed and made into a plate by a steam roller, may be fragmented, cut up by a biscuit-cutting machine, but he gets up immediately, intact and full of life, in the next shot. So it seems obvious to me that the American cartoon, rather than glorifying death, is a permanent illustration of the theme of rebirth.’

Getting the bird

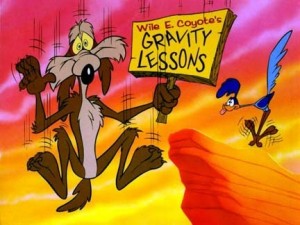

This sounds quite fitting in relation to the unswerving optimism and quixotic faith in his own ingenuity held by Wile E. Coyote as he repeatedly endeavors (and fails) to trap the Road Runner — suffering grotesque accidents and indignities all the while — in a series of cartoons launched by Chuck Jones in 1948.

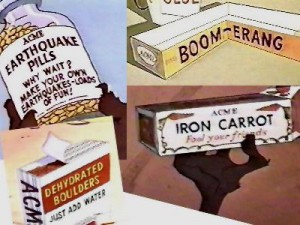

But if Tom and Jerry, like Bugs and Elmer, can be regarded as antagonistic characters who are generally accorded nearly equal status, it might be argued that the Road Runner, by way of contrast, is scarcely a character at all. More precisely he appears to be an almost impersonal force in the universe — a force bent on tempting, testing, eluding, defeating and then once again inspiring the indefatigable Coyote to try again with his wide and inexhaustible assortment of Acme implements.

Indeed, the endlessly repeated gags and actions in Road Runner cartoons are invariably perceived from the vantage point of the hapless Coyote — a character as well-developed as Bugs Bunny or Jerry Mouse (who, significantly and unlike Elmer or Tom, are also frequently characterized through their personal selections of domestic furnishings, in caves, holes and crevices) — although he never utters a word. The fact that Chuck Jones was central to the development of Bugs, Coyote, Daffy Duck, Speedy Gonzales, Sylvester the Cat and other cartoon favorites at Warners may help to explain why these characters intermittently seem to share some of the same tired humanity in their plaintively drooping features — above all, immediately before and after disaster strikes them.

As a rule, an audience feels less mitigatingsympathy (or empathy) for a Road Runner or a Woody Woodpecker because they are not substantial enough as personalities to encourage such sentiment. Woody was an invention of Walter Lantz at Universal around the same time that Avery and his cohorts were concocting Bugs Bunny at Warners. Lantz’s honorary Academy Award in l979 emphasized, in particular, his creation of this cheerful, noisy bird. An aggressive plumed creature with a somewhat abrasive five-note hoot of triumph that was musically integrated into his theme song, Woody can perhaps best be compared to Screwy Squirrel — an aberrant Avery creation who lasted through only five cartoons in the mid-Forties — as a set of loony, hysterical reflexes rather than a full-blowncharacter.

By the same token, the Woody Woodpecker cartoons — animated over the years by Shamus Culhane, then Don Peterson and later Paul Smith — can sometimes be regarded as pleasurable with or without the behavioral charms of their hero. More often than not Woody was a prop in setting up gags rather than a comic persona in his own right. In The Hypnotic Hick (1953) — one of the few cartoons made in 3-D — he is characteristically cast as a delivery boy who has to present a letter to a buzzard on a construction site, a mere conduit in the chain of visual gags.

The coolest cat

Much the same could be said for a later cartoon character, the Pink Panther, however removed the Panther’s suave demeanor may be from the woodpecker’ s shrill hyperventilation. Considering that the Panther’s debut was in the animated credits of Blake Edwards’ live-action The Pink Panther (1963) — the feature which also introduced Peter Sellers’ bumbling Inspector Clouseau — it seems possible that cartoon director Friz Freleng (a former Bugs Bunny animator) and animator Ken Harris might have taken some of their inspiration from the debonair David Niven — another star in the film — in delineating their animal’s cool composure. The blander virtues of the American television cartoon The Pink Panther Show, produced by Freleng and David H. DePatie, can perhaps be ascribed to the built-in blandness of the medium itself — with its pumped-in laugh tracks giving home viewers less opportunities to think or feel for themselves. These Pink Panther cartoons are, on the whole, less violent than Forties cartoons though the Panther, embarking on some quest to satisfy his curiosity or prove his determination, is occasionally badly injured. The more horrendous casualties, however, are reserved for the Clouseau cartoon character, often left charred black by a stick of dynamite thrust back at him at the crucial moment by his adversary (usually a fat French villain with a broken nose and a five o’clock shadow).

The limitations imposed by television are noticeable in the work of other Hollywood animators: Avery’s commercials for an insect spray and powdered soft drink (the latter featuring Bugs Bunny) and Hanna-Barbera characters like Yogi Bear, Huckleberry Hound and the Flintstones. Among the heavyweights it appears that only Chuck Jones has been fortunate enough to preserve his autonomy in TV specials — reminding older viewers what anarchistic cartoon slapstick was really like when Hollywood was in its heyday.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM