This piece appeared in the Chicago Reader on December 10, 2004. One particular reason for reviving it is the happy news that The Exiles (see first illustration below) and all the Val Lewton horror films, including The Seventh Victim, which were relatively scarce items when they showed back then at the Gene Siskel Film Center, are now readily available on DVD, in excellent editions. Due to its lack of the usual auteurist credentials — specifically, the mediocre reputation of Mark Robson — The Seventh Victim continues to be the most neglected of Lewton’s greatest films, but it’s no longer hard to find. Burn, Witch, Burn is now out on Blu-Ray, and it seems that A Tale of Two Sisters is currently available in multiple editions in the U.S. and elsewhere — J.R.

The Exiles **** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Kent Mackenzie

With Yvonne Williams, Homer Nish, Tommy Reynolds, and Rico Rodriguez

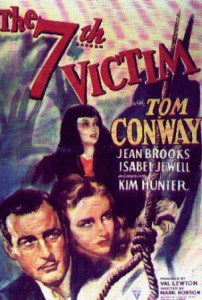

The Seventh Victim **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Mark Robson

Written by Charles O’Neal and Dewitt Bodeen

With Kim Hunter, Jean Brooks, Hugh Beaumont, Erford Gage, Tom Conway, and Mary Newton

A Tale of Two Sisters * (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by Kim Jee-woon

With Yeom Jeong-a, Im Soo-jung, Moon Geun-young, and Kim Kab-su

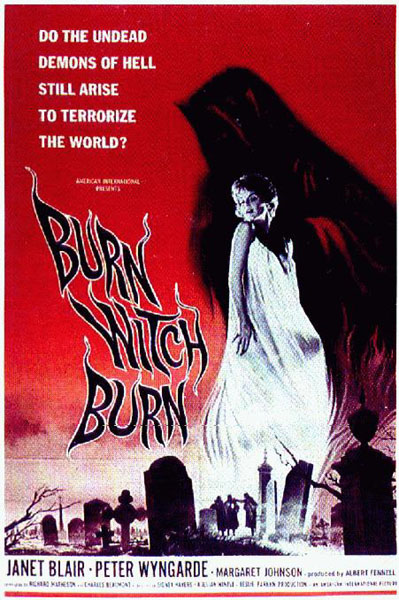

Burn, Witch, Burn *** (A must see)

Directed by Sidney Hayers

Written by Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont

With Janet Blair, Peter Wyngarde, Margaret Johnston, and Anthony Nicholls

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Few movie-industry executives -– and not just in the U.S. -– understand the value of the older films in their vaults, and as a consequence many masterpieces and other exceptional releases have languished there for decades. Relatively unsung treasures of the past tend to become available again, in new prints or on video or DVD, but only on the rare occasion when a film buff is in charge.

Two 1961 films showing at the Gene Siskel Film Center this week and one from 1943 that will screen there in January qualify as casualties of this neglect -– and of lack of imagination in classifying them. One of the ‘61 films, The Exiles –- a low-budget independent feature that follows a few uprooted Native Americans over a 12-hour period in the Bunker Hill district of Los Angeles –- can hold its own next to John Cassavetes’s Shadows, which came out a year earlier. The Exiles was featured on the cover of Film Quarterly in the early 60s and was well received at the Venice film festival. It has beautiful high-contrast black-and-white photography, a dense and highly creative sound track, and moving portraits, and it’s refreshingly free of cliches and platitudes -– all the makings of an instant classic. Yet it vanished for almost four decades, until filmmaker Thom Andersen revived it by highlighting it in his remarkable essay film Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003) and screening it with his film at festivals and other venues.

The reasons The Exiles disappeared include the early death of its writer-director, Kent Mackenzie, who made only one subsequent feature, and its origins on the west coast, which undoubtedly limited its east-coast bookings. (The latter makes me wonder if we’d ever have heard of Shadows if Cassavetes hadn’t come from New York and been a tireless self-promoter.) Perhaps even more relevant is one of The Exiles’s greatest virtues –- the way it combines documentary and fiction, using nonprofessional actors who lip-synch their characters’ dialogue and improvise internal monologues about their lives.

How does one label such a film? The Internet Movie Database calls it a documentary, which is about as misleading as calling it ethnographic because it deals with Native Americans. Calling it fiction isn’t quite accurate either. “You could call it neorealist, since it comes from outside the Hollywood studios,” Andersen notes in Los Angeles Plays Itself, though a little later he adds that it’s 15 years ahead of the Los Angeles neorealist movement spearheaded by black directors such as Charles Burnett. “You could call it independent,” Andersen adds, “but it’s not exactly Pulp Fiction.” You could also say that it stands outside any clear genre or movement, which undoubtedly helped condemn it to invisibility.

Another casualty of industry ignorance is The Seventh Victim (1943), a no less original B picture about devil worshippers in Greenwich Village, showing at the Film Center as part of its series “Horror for the Holidays: Occult Cult Films.” It’s my favorite horror film. Some people might argue that it isn’t a horror film because nothing even bordering on the supernatural occurs. Yet it’s pervaded by a palpable sense of dread, menace, and doom, and its believability only makes this more frightening.

The film was produced at RKO by Val Lewton, who’d once been David O. Selznick’s story editor and who inspired parts of the producer hero played by Kirk Douglas in Vincente Minnelli’s Oscar-worthy The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), an insider’s look at Hollywood. Lewton invented a new kind of horror film that achieved its apotheosis in his first four features –- Cat People, I Walked With a Zombie (also showing at the Film Center in early January), The Leopard Man, and The Seventh Victim –- though his remaining five (The Ghost Ship, The Curse of the Cat People, Isle of the Dead, The Body Snatcher, and Bedlam) are nothing to sneer at. The poetic cinema he conjured out of his minimal sets and literary ambience –- The Seventh Victim, for instance, begins and ends with a quote from John Donne’s first “Holy Sonnet” -– is largely the result of suggestion, calculated to coax the imagination into filling in all the blanks. Much of this subtlety was the product of budgetary, time, and thematic constraints: each feature had a maximum budget of $150,000, couldn’t run longer than 75 minutes, and had a lurid title the studio arrived at by test-marketing. Some of these films were sleepers: Jacques Tourneur, who directed the first three (as well as the Lewtonlike Curse of the Demon 15 years later), was fond of noting that Cat People did better at the box office than Citizen Kane. (The Seventh Victim fared less well, perhaps because audiences found it too upsetting.)

Lewton’s body of work deeply affected the evolution of the genre. There have been two main strains in horror films since the 40s, one honoring Lewton’s aesthetic, the other dismissing it in favor of a pile-driver approach. This pile-driver approach -– represented in England by Hammer pictures and in the U.S. by the shower murder in Psycho (1960) and the gross shock effects of The Exorcist (1973), Carrie (1976), and A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), among others –- has sold more tickets and garnered more press. But the Lewton tradition -– which can be seen in the work of others as early as 1944, when The Uninvited was made -– has never disappeared. It’s apparent not only in Curse of the Demon but in everything in Psycho preceding the shower murder, as well as in such diverse movies as The Innocents (1961), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Blair Witch Project (1999), and even another neglected “occult cult” item playing at the Film Center this week, the 1962 English fantasy Burn, Witch, Burn.

A more diluted example –- roughly three parts pile driver (or Brian De Palma) to one part Lewton –- is the 2003 South Korean chiller A Tale of Two Sisters, opening this week at Landmark’s Century Centre. The problem in this case is that we aren’t meant to understand the story fully until the film’s closing minutes, so the shocks and suggestions come in a muddled context. In any Lewtonian movie worth its salt some sense of everyday reality is needed before the creepy possibilities can arise. But here that order is reversed, and by the time we have something resembling a real world to conjure with, the picture’s all but over.

I only recently realized that The Seventh Victim was my favorite horror film. I was looking at a list of my 1,000 favorite films, which had asterisks next to 100 I preferred most, and saw that The Seventh Victim was the only horror movie among them. This movie creeps up on you in more ways than one. Its urban poetry may have been created inside a studio, but it’s no less potent than that found in The Exiles, which also projects a mood of meditative melancholy as solitary women take long walks at night.

What’s remarkable about the poetry in The Seventh Victim is that it manages to coexist gracefully with a fast-moving plot, over a dozen important characters who have complex and nuanced relationships, and a running time of only 71 minutes. The narrative is so condensed that there are a few minor lapses in the continuity, though the scenes in the original script that would have provided this continuity -– along with a much more conventional ending -– wouldn’t have been improvements. The film feels both cozy and oppressive as it deals frankly with one character’s death wish, familial and romantic love, the power of a cult to drive a member toward suicide, the sustaining warmth of a circle of friends, and the seductive allure of both art and oblivion. Here, as elsewhere in Lewton’s oeuvre, belief in the supernatural is used mainly to evoke, contain, or account for a certain kind of emotional excess.

Lewton produced 14 films in all. None is currently available on DVD in the U.S., though all the horror films are on video. In France six of these are on DVD, though not The Seventh Victim. I’m not the only one who regards it as Lewton’s greatest film, and I assume the main reason for its neglect is auteurist thinking -– only directors are seen as auteurs –- and the absence of stars. (The lead role is played by Kim Hunter in her first film performance; eight years later she was Stella in A Streetcar Named Desire.) The director is Mark Robson, one of the two editors on Citizen Kane (the other was Robert Wise, who also launched his directorial career by making several films for Lewton). The only Robson-Lewton film on DVD is Bedlam (1946), probably because it stars Boris Karloff.

Robson’s subsequent directorial credits -– ranging from Champion and Home of the Brave in the 40s to schlock such as Peyton Place (1957), Valley of the Dolls (1967), and Earthquake (1974) -– never gave him any sort of auteurist profile, unlike Tourneur and Wise. The Seventh Victim has an auteur, but it’s clearly Lewton. He never took a writing credit on his films, but he worked on all the scripts. The story in The Seventh Victim is almost entirely his, making it his most personal film. Its lyrical West Village seems created out of his own early years there, when he was a hack writer in his 20s churning out novels, nonfiction books, and radio scripts. He worked fast, sometimes writing the second half of shows while the first half was being broadcast -– which must have taught him something about economy.

There’s even a self-referential side to The Seventh Victim. Dr. Judd (Tom Conway, brother of George Sanders) is a lecherous psychoanalyst in Cat People who’s killed by one of his patients, the frigid heroine, after he makes a pass at her and arouses her deadly panther persona; Judd is cleverly used to discredit Freud and sabotage psychological explanations for the heroine’s nature. In The Seventh Victim Judd is resurrected without explanation and eventually made more sympathetic, as if Lewton were determined to give him a second chance: he’s one of the film’s two sages, embodying worldliness and science (the other sage is a lonely poet). There’s also a jolting, quintessentially Lewtonian moment, which used to be known in the trade as a “bus shot,” after a bus that suddenly enters a shot at a tense moment in Cat People, causing viewers to leap out of their seats. A similar shock occurs in The Leopard Man, and the one in The Seventh Victim comes when a dog overturns a garbage can lid. This is probably the only part of the Lewton legacy that was appropriated by the pile drivers, with De Palma heading the list.

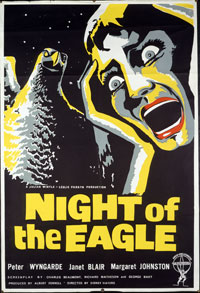

Burn, Witch, Burn –- yet another casualty of industry obliviousness –- adapts an American novel, Fritz Leiber’s Conjure Wife, to an English setting with English actors, though the two credited adapters, SF and fantasy writers Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont, are both American. The film has no other prestigious names attached to it, so it’s not surprising that it isn’t well-known.

The story’s set in and around a rural medical college, and its premise is that some local women are secretly witches practicing either white or black magic. The hero (Peter Wyngarde), a somewhat vain professor who scoffs at the very idea, discovers to his dismay that his devoted wife has been casting spells to help his career. She claims she’s doing it to counter the evil spells of another faculty member envious of his success, and the remainder of the film carries us through frightening events that alternately seem to confirm or cast doubt on this.

The hero initially denies that anyone in his department is plotting against him, suggesting that he’s less attuned to reality than his wife, and the ambiguities only proliferate from there. All the characters are boringly conventional until the subject of witchcraft comes up, which calls attention to their quirks and makes them immediately more interesting. Is the love-stricken student who accuses the professor of raping her having a nervous breakdown, driven by a spell, or some combination of the two? Is the professor’s wife’s near suicide attributable to her unbalanced state, to a spell that’s put her into a trance, or both?

The film seems to suggest that witchcraft both exists and works, but the uncertainty we continue to have about some events and characters is a mark of Lewton’s influence. Unfortunately, the film also seems to distrust uncertainty and shifts to pile-driver effects. Over its course, director Sidney Hayers, a TV veteran, cuts no fewer than 17 times to a huge stone eagle poised high above the front door of the college’s main building to suggest menace before the thing finally comes alive and chases after the hero. (The film’s original English title is Night of the Eagle.) The movie does a pretty good job of handling this fantasy sequence, but the rhetorical nudges building up to it are tiresome because they trust the audience’s initiative so little.