From the Chicago Reader (April 12, 1996). — J.R.

A Family Thing

Directed by Richard Pearce

Written by Billy Bob Thornton and Tom Epperson

With Robert Duvall, James Earl Jones, Michael Beach, Irma P. Hall, David Keith, Grace Zabriskie, Regina Taylor, Mary Jackson, Paula Marshall, and James Harrell.

If good quiet movies seem as rare as hen’s teeth nowadays, one reason is that they’re gone before most of us get around to seeing them. As a rule, it’s the loud movies, good and bad (usually bad), that claim our attention first — the ones that yell at us from afar through monster ad campaigns tricked up with socko clips and hyperbolic quotes. Those that speak to us in a normal tone of voice, without flash or filigree, seep into our consciousness more gradually — and gradual discoveries are fast becoming impossible given that the commercial fate of a new feature is often sealed the opening weekend.

The first time I saw A Family Thing — not only the best but pretty nearly the only good quiet Hollywood movie I’ve seen this year — was at a press show in late February, back-to-back with The Birdcage. It took me completely by surprise — unlike The Birdcage, which had been shouting from the rooftops for months — and when I finally got around to seeing it a second time I found it every bit as affecting. It was only the second week of its run at Webster Place, but the house was far from full.

The little I’d heard about A Family Thing in advance made me curious but skeptical. It sounds awfully contrived: Earl Pilcher Jr., a man in his 60s from small-town Arkansas who sells and rents tractors (Robert Duvall), discovers after the death of the woman he believed was his mother that his real mother was a black maid who worked for his family and died in a shack giving birth to him.

The woman who raised him imparts this startling fact to him in a letter to be read only after her death, in which she urges him to find his slightly older half brother, Ray Murdock (James Earl Jones), a black policeman living in Chicago, and get to know him “as your family.” Earl can hardly believe this revelation, but when he confronts his father he receives as confirmation the old man’s mute tears. Soon afterward Earl decides to drive to Chicago in his pickup truck without telling either his wife or his grown daughter what he’s discovered. The remainder of the movie charts his getting acquainted with Ray and his family — his Aunt T. (Irma P. Hall), now blind, and his son Virgil (Michael Beach), a bus driver, both of whom live with him, and Virgil’s estranged wife and their two little girls.

In one sense, this seemingly melodramatic plot premise is contrived, registering more as myth than as real possibility. Yet thanks to what the movie has in mind and especially what the actors bring to it, it’s a lovely myth, one that has the ring of deeply felt truth. The story is a specifically southern myth — both screenwriters, Billy Bob Thornton and Tom Epperson, who also wrote One False Move, hail from Arkansas — founded on the everyday intimacy among black and white people in the deep south that persists in spite of all the taboos against recognizing and acknowledging it. The movie chronicles the working out of that recognition and acknowledgment as it takes shape between a few individuals over a few days, and for this reason the plot premise becomes a fully functional contrivance rather than a gimmick exploited for shock effect. In other words, the situation that gives rise to this drama is exceptional, but the experience underlying it is universal — an experience that everyone working on the movie appears to understand. It’s an experience that tells us we’re all much more related to one another than we’re usually ready to admit.

From this standpoint, A Family Thing is a kind of down-home version of John Cassavetes’s Shadows, and the fact that Earl is played by a white man becomes central to the overall ethical and emotional tenor of the work. (In Shadows, a white actress, Lelia Goldoni, played a mulatto alongside Hugh Hurd, a black actor playing her black brother — though Goldoni’s impersonation became more complex because a second brother was played by someone who’s actually a mulatto, Ben Carruthers.) As in Shadows, direct discussion of racial differences tends to be played down in the dialogue, so that the drama consists largely of highly nuanced behavioral subtexts. Another parallel is that race relations in the world outside the sphere of the central characters exist as a kind of nonfunctional abstraction — which is to say that everything in the story is left up to the actors, who shoulder this responsibility quite admirably. (The direction, by Richard Pearce — whose recent credits include The Long Walk Home and Leap of Faith — is the most sensitive I’ve seen from him, particularly in the various ways he accommodates and even celebrates the bodies of his actors in relation to a ‘Scope frame.)

The central idea for A Family Thing originated with Robert Duvall, one of the film’s three producers, who commissioned a script from Thornton and Epperson. Duvall certainly shines in the lead part, which was written for him, but the two most impressive performances are by James Earl Jones and Irma P. Hall.

Admittedly, my preference may have something to do with the moral size of these characters rather than the craft and imagination invested in each part. A similar bias tends to influence the results of Academy Awards and other such competitions, just as it tends to warp many of our judgments of actors. In this case I may have been put off by Duvall’s past handling of related roles (e.g., the Mississippi handyman in the 1972 feature Tomorrow, adapted from a short story by William Faulkner).

In any case, Duvall is certainly letter-perfect as Earl Pilcher Jr., though in certain ways the character seems underscripted; so much emphasis is placed on his struggle with accepting his redefined racial identity that we may have trouble imagining the previous 60-odd years of his life. There may also be something a little too generic about Earl as a hillbilly: not quite as generic as Charles Gross’s highly cliched score for the film — which consists mainly of a harmonica, guitar, and piano playing as if “country” were stamped on every note — but still closer at times to a type than an individual.

The same can’t be said of James Earl Jones, whose major accomplishment is to make Ray Murdock the individual triumph over type. (If Ray’s deep-bellied laughter at times suggests a cliche, the quirky placement of his laughter within scenes and the even more unpredictable occurrences of his stutter conjure up the complexities of a living, breathing individual — an astonishing piece of work. And when it comes to Irma P. Hall as Aunt T. — a loving curmudgeon and fussbudget who functions as the prime mover in the coming together of Earl and Ray — type and individual seem to arm-wrestle each other to an eloquent standstill.

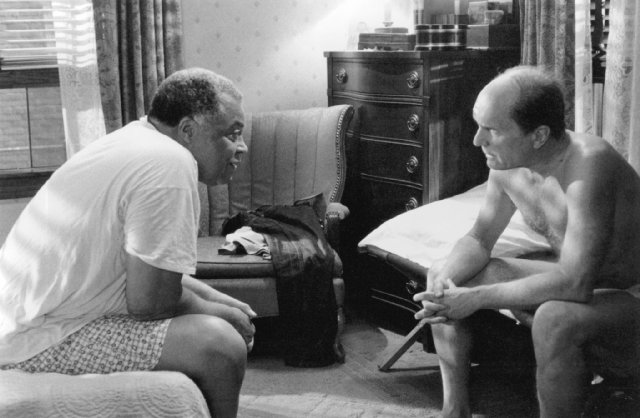

Each of these three wonderful actors gets a climactic monologue and scene of his or her own. The first and best of these occurs in my favorite sequence in the movie, when Ray and Earl recount parts of their separate and common pasts as they get ready for bed. Ray gives an account of the three people in his life who saved him, a short speech that works wonders in suggesting portions of a life that are kept offscreen. Then comes Earl’s attempt to offer some fatherly advice, in the form of a long personal anecdote, to a mainly resistant Virgil on the sidewalk outside an inner-city bar — “a hillbilly lecture,” Virgil calls it — that points simultaneously to Earl’s inadequacy at such a task (the scene’s ostensible main focus) and to his own discovery that he’s proud to have Ray for a brother (the scene’s apparent subtext, though it winds up overwhelming everything else). Finally, Aunt T.’s monologue, the longest, becomes the voice-over narration for a flashback in sepia as she recounts the circumstances of Earl’s birth to Earl and Ray — a scene that becomes the movie’s climax by clarifying everything that precedes it.

In a sense, Aunt T. — who serves as seer and emissary between the worlds of Ray and Earl — is the movie’s most eloquent spokesperson, so it seems appropriate that the final roller credits appear over her, walking in her Chicago neighborhood with her cane and parasol to the strains of a gospel tune (thoroughly generic, but with much more lift than the insufferable harmonica whines). In a movie that contrives to reinvent portions of both Arkansas (filmed in Tennessee) and Chicago as backdrops for its talented cast, one could argue that it’s the acting that creates the landscape.