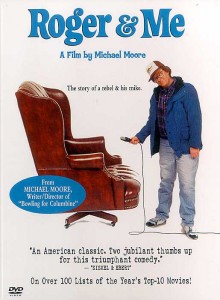

From the Chicago Reader (February 2, 1990). — J.R.

ROGER & ME

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Michael Moore.

There’s no question that you should see Roger & Me if you haven’t already. Michael Moore’s comic documentary about the devastation of Flint, Michigan, resulting from General Motors’ massive plant closings and job layoffs is the most entertaining American documentary to come along in years. Better yet, Roger & Me is radical in its angry critique of the Reagan era — its legacy of corporate greed and its cheerful heartlessness — in a way that makes contemporary Hollywood movies seem cowardly and conformist.

The story of how Michael Moore, a journalist from Flint with no prior filmmaking experience, financed his first feature is an American success story with an inspirational value all its own. Moore sold his house and furnishings, organized local bingo games, invested his settlement from a wrongful-discharge lawsuit against Mother Jones (where he briefly served as editor), and collected hundreds of small investments from Michigan residents to raise his $160,000 budget. After the film became a popular hit and prizewinner at several film festivals last fall, it was picked up by Warners for $3 million and is already well on its way to becoming an independent sleeper. Remarkably accomplished for a first film — streamlined, agreeably fast-paced, deftly organized, full of laughs and surprises — it seems to prove that an outsider to the film industry can still make it into the big time.

The film’s slender story consists of two layers: (1) what has happened in Flint during the 80s, specifically in conjunction with General Motors’ closing of 11 plants and laying off of 35,000 workers, and (2) Moore’s unsuccessful attempts to buttonhole General Motors chairman Roger Smith, who was responsible for the layoffs, and bring him to Flint to see the consequences of his actions: massive evictions of unemployed workers, a rat population explosion, a soaring crime rate, and other diverse horrors that have made Flint, according to Money magazine, the worst place to live in America.

Regarding the first layer, Harlan Jacobson, the former editor of Film Comment, recently pointed out in that magazine that Moore’s implied (if unstated) chronology of events is somewhat at variance with the historical record. A visit by Ronald Reagan to Flint to cheer up unemployed workers, for instance, took place in 1980 — before Reagan was president, and six years before Roger Smith closed the plants. Similarly, Flint’s Hyatt Regency and Auto World theme park (two attempts by town fathers to pump life into the town’s economy) opened in 1982 and 1984, respectively, long before the massive layoffs in ’86 and ’87. Although none of this fancy footwork necessarily invalidates any of Moore’s major points (which are made more directly and without any of the same chronological ambiguity in an article he wrote for the June 6, 1987, issue of the Nation headlined “General Motors Pulls Out: In Flint, Tough Times Last”), Jacobson takes the peculiar position that it’s cause for extreme moral outrage, even going so far as to compare Moore’s minor distortions to President Johnson’s lying about the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

Jacobson’s findings are certainly worth noting, although his hysterical reaction seems needlessly hyperbolic and misplaced. Slick journalism routinely traffics in such minor distortions (and Jacobson’s own uncritical embrace of glitzy writing in Film Comment over the past several years, as editor and writer, has been far from exemplary). Consider most of the recent reporting by the national media of the U.S. invasion of Panama — which blithely transformed a statement by Noriega from the Spanish subjunctive along the lines of “It’s as if we were at war with the U.S.” to “We are at war with the U.S.,” and which devoted much more attention to whether or not Bush was a “wimp” than to how many international agreements he was gleefully violating — and the issue of whether Michael Moore elides a few dates looks like pretty small potatoes.

Worst of all, Jacobson’s emphasis completely bypasses a much larger problem — a matter of style and tone that is a good deal harder to separate from the film’s strengths and virtues. Moore’s chronological tinkering can be regarded as one of the many symptoms of this problem, but it is far from central. Much more to the point, I think, is what Roger & Me does with and to an audience’s sense of humor — and beyond that, what it has to do in order to receive the acclaim and attention it has been getting.

I’m not excluding myself from the audience. Roger & Me made me laugh uproariously both times I saw it; it also made me sick — not only about what it had to say, but also about how it was saying it, and how I and many others in the audience were enjoying it. On some level, we were being invited to laugh at our own defeat as human beings, our incapacity to affect Roger Smith’s conscience any more than Michael Moore could. And of course Moore’s odyssey with a film crew, undertaken to track down Smith, like much else in the film, smacks of a setup and self-fulfilling prophecies. I suspect that he wants us to laugh at his own impotence and our own as a way of goading us into action; but if that’s the case, he doesn’t even begin to show us what form that action could take.

The movie provides us with cheap feelings of moral and intellectual superiority to most of the targets of Moore’s comic venom, a varied cast of characters that includes many victims other than corporate villain Smith. Sharing Moore’s scorn, one is often made to feel as protected as a tourist in a zoo. Because ours is a period when victims are held in such contempt that they don’t even qualify as martyrs — the contemporary synonym for “martyr” being “loser” — the only way that Moore can grab us by the lapels, it seems, is to invite us to laugh at our own helplessness and self-hatred.

Writing about Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove in Partisan Review 16 years ago, Susan Sontag noted with some distress certain aspects of the film’s widespread appeal. She observed that liberal intellectuals who caught the film in previews prior to its release “marveled at its political daring, and feared that the film would run into terrible difficulties (mobs of American Legion types storming the theaters, etc). As it turned out,” she continued, “everybody, from The New Yorker to the Daily News, had kind words to say about Dr. Strangelove; there are no pickets; and the film is breaking records at the box office. Intellectuals and adolescents both love it. But the 16-year-olds who are lining up to see it understand the film, and its real virtues, better than the intellectuals, who vastly overpraise it. For Dr. Strangelove is not, in fact, a political film at all. It uses the OK targets of left liberals (the defense establishment, Texas, chewing gum, mechanization, American vulgarity) and treats them from an entirely post-political, Mad Magazine point of view. Dr. Strangelove is really a very cheerful film. . . . The end, with its matter-of-fact image of apocalypse and flip soundtrack (“We’ll Meet Again’), reassures in a curious way, for nihilism is [our] contemporary form of moral uplift. As [Chaplin’s] The Great Dictator was Popular Front nihilism for the masses, so Dr. Strangelove is nihilism for the masses, a philistine nihilism.”

I don’t think it’s entirely correct to say that Dr. Strangelove wasn’t a political film in the mid-60s. I wasn’t a 16-year-old when I first saw it, but a college junior, and I wasn’t the only one who found it deeply disturbing as well as funny; I even recall a classmate who emerged from the movie in tears, shaken to her core. But I think Sontag still has a point about how Dr. Strangelove can be read apolitically, and some of the same strictures can be applied to Roger & Me, which is even more overtly political. (One thing among others that makes it more political is that 1990 is not 1964; the current extreme timidity of the American cinema about political matters is part of the context that gives Moore’s film such a bracing edge.) And it seems to me that the remainder of Sontag’s misgivings about Dr. Strangelove apply to Roger & Me in spades.

Consider, for starters, the relationship of Roger & Me to two of the most popular pictures of last year, both of them characteristically and resolutely apolitical: Batman and Crimes and Misdemeanors. Part of the charge we get from Moore’s documentary stems from the perception that it is practically alone in offering a critical view of what’s been happening in this country. But in other respects, the degree to which Roger & Me shares feelings and attitudes of hits like Batman and Crimes and Misdemeanors — including a sort of uplifting pop nihilism — is grimly significant.

To begin with, all three movies express the conviction that our world is being run into the ground by scoundrels and lunatics, and convey a feeling of total helplessness in relation to this situation. Oddly enough, the strong public responses to all three movies suggest that if they were any less pessimistic or defeatist they’d be less popular. Wittingly or not, they all derive much of their entertainment value from somewhat cruel black humor at the expense of a frustrated and ineffectual hero — Bruce Wayne/Batman (Michael Keaton) in Batman, a serious but failed documentary maker named Cliff Stern (Woody Allen) in Crimes and Misdemeanors, and Moore himself in Roger & Me — who is less a target for ridicule than a conduit through whom ridicule can be deflected onto other victims or stooges. All three movies have a powerful, amoral villain who elicits a certain amount of uneasy envy or admiration: Jack Nicholson’s Jack Napier/Joker in Batman, Alan Alda’s smarmy TV producer in Crimes and Misdemeanors, and Roger Smith in Roger & Me. Some of the cruelty can be felt in the ways that we are asked to enjoy the Joker’s “artistic” murders and media crimes, the recounting by Cliff Stern’s sister of her humiliation by a sadistic pervert she met through a classified ad (and Stern’s horrified responses, which are telegraphed to an audience as gag lines), and the evictions of unemployed workers from their homes in Flint at Christmastime, presumably at the same time that Roger Smith is delivering his fatuous Christmas message.

Ironically, Batman is the only one of these three pictures to own up to its own perversity — in this case one winds up preferring the creativity and vitality of Jack/Joker (a virtual blood brother of Alex in Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange) to the humorless rigidity of Bruce/Batman, who’s about as charismatic as J. Edgar Hoover. But Batman also happens to be the only one of the three in which the forces of “good” triumph. The other two postulate a contemporary moral crisis without investing the major victims of this crisis — the ophthalmologist’s mistress (Anjelica Huston) in Crimes and Misdemeanors, the unemployed autoworkers in Roger & Me — with the roundness and humanity that would make them more than cliched abstractions. (Moore has been quite explicit about his own rationale for this in interviews — his desire to entertain an audience, not show them the unemployment lines that they can see on the news — although he has been less forthcoming about the dehumanization that results from this strategy.) If an audience’s compassion is directly solicited by anyone, it’s by actors-filmmakers Allen and Moore, sad sacks who serve as spokespeople for a despairing but complacent audience — that “nihilism for the masses” alluded to by Sontag.

Granted, Moore’s vantage point is strictly that of the disenfranchised working class while Allen’s is that of the comfortable white bourgeoisie, and both films, unlike Batman, launch frontal attacks against the callous ruthlessness of the rich. But when it comes to audience responses, it appears that upper-middle-class viewers feel rewarded and enlightened rather than challenged or attacked by Crimes and Misdemeanors (which attacks self-interest only halfheartedly insofar as it is incapable of seeing beyond it to any alternative), and yuppie viewers don’t appear to have too much trouble laughing at their counterparts in Roger & Me. (I should add, however, that there was less laughter at a private screening that I attended, which was held mainly for Chicago executives, than there was at a press screening at the Toronto film festival.) The narcissistic anguish of Allen’s guilty ophthalmologist is what scores with the audience rather than the actual murder that occasions it (Anjelica Huston is an expedient prop, not a character one is supposed to care about), just as the witty scorn of Allen and Moore — as hapless, impotent observers — for their enemies and fellow victims alike is what one is finally asked to identify with.

One thing that makes me feel unusually conflicted about Roger & Me is that just as I think there are certain wrong reasons for liking it, I also think there are certain wrong reasons for disliking it. The mistrust and sheer hatred many of my colleagues feel for films that take strong and unambiguous political stands make it all too easy for them to seize on Moore’s shortcomings — his snobbishness and his cavalier handling of chronology — as excuses for dismissing his movie completely. Over the past couple of years, the widespread critical dismissals of Walker, Parents, and Fat Man and Little Boy, among other pictures — as well as the avoidance by critics of documentaries like Coverup: Behind the Iran Contra Affair — has tended to follow a similar pattern. The point isn’t whether or not these films are flawed — how many movies nowadays aren’t? — but whether they’re being dismissed out of hand so that the critics won’t have to deal with their contents.

Roger & Me has been canny enough to break through this barrier and engage most critics with its subject, which is entirely to its credit. If only it didn’t stoop to such cheap tactics as getting us to laugh at the warfare in Tel Aviv, played behind the closing credits, I’d have fewer qualms about it. (This slaughter becomes the punch line to the comment of Maxine, a Flint citizen trying to pump up the town’s business section, who notes that she’s going to Tel Aviv and adds, “Maybe I’ll be the minister of tourism.”) Even with those qualms, I have to admit that Moore does a much better job of reporting than a network news program might. That may not be enough, but it’s plenty for starters.