From the Chicago Reader (July 28, 2000). — J.R.

Shower

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Zhang Yang

Written by Liu Fen Dou, Yang, Huo Xin, Diao Yi Nan, and Cai Xiang Jun

With Zhu Xu, Pu Cun Xin, Jiang Wu, He Zheng, Zhang Jin Hao, Lao Lin, and Lao Wu.

In these pages last week I wondered whether adapting Marcel Proust was the best way for the talented Raul Ruiz to spend his time. Later I heard from some colleagues who write for suburban papers that their editors had forbidden them to review Time Regained — a standard form of censorship that made me wonder whether my expressing misgivings would encourage the editors to believe they were justified. Especially stomach turning was the spurious reason they reportedly gave: that people in the burbs wouldn’t care about such a movie.

But what else would persuade a suburbanite to travel all the way to Chicago to see a film if not something like Time Regained? Surely not a chance to see The Patriot on a slightly bigger screen (democracy at work: we can choose where to see bad summer movies). I suspect that the contempt these suburban editors have for their readers is a form of fear: if they admitted that better fare was available elsewhere, the studios might get annoyed and withhold some of their advertising dollars. In effect, this is a replay of a classic Stalinist scenario, with a smiling Jack Valenti taking the place of folksy Uncle Joe.

Editors who depend on studio ads aren’t our only cultural commissars. Chicago Tonight, for instance, doesn’t fit that category, yet its desire to genuflect toward southern California was certainly evident both times I appeared on the show. The first time was during the Oscar hoopla in 1994; the second was the day after Christmas two years later, when I agreed to appear only if I’d be allowed to speak not just about studio releases but about a couple of independent movies, one of them foreign: Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man and André Téchiné‘s Thieves. John Callaway, the host, finally made good on his promise by allowing me to mention them for a few seconds over the show’s final credits.

Now I’m faced with what to say about a foreign movie that’s conceivably more audience friendly than Time Regained, Dead Man, and Thieves combined. Shower, playing this week at the Music Box, is a cheerful crowd pleaser from mainland China that’s been entertaining audiences across the globe for the past year. Seeing it recently with a Cinema/Chicago crowd, I felt something I hadn’t till then felt in a Chicago movie house this summer — that all of us in the audience were having a good time. Is this because most Cinema/ Chicago members don’t hail from the suburbs? I doubt it.

I’m not saying that we were transported or whipped into a frenzy or even profoundly enlightened. But we weren’t bored, we were often amused, and I think we liked being where we were. This was an everyday sort of movie experience when I was growing up, and I’ve experienced it periodically since then — mostly, I confess, at Hollywood movies, though not at any I’ve seen lately. This makes it tempting to call Shower a movie that reinvents routine Hollywood. It’s not quite detailed enough to suggest John Ford, though there’s a similar focus on community and tradition, rituals and running gags. A piece of Depression uplift such as the 1937 One Hundred Men and a Girl, costarring Deanna Durbin and Leopold Stokowski, probably provides a better Hollywood reference.

There are plenty of other such populist movies around these days. Community is a tried-and-true Hollywood subject, but sadly we get relatively little of it in American movies nowadays. We can get plenty of it in movies from elsewhere (Samira Makhmalbaf’s Blackboards, which I caught in Pesaro, Italy, last month, recalls in spots a Ford western, Wagonmaster in particular). If we don’t hear more about these movies, it’s probably because the multimillion-dollar promotional budgets for bad American movies overwhelm them.

Shower is special in that the odds are somewhat better that you’ve heard of it. It’s won audience awards for most popular film at festivals on both sides of the Atlantic and has generally made a big impression in Asia, Europe, and North America — just about everywhere, in short, except for the American suburbs, which are allegedly too underdeveloped for any movies with subtitles, no matter how simpleminded or enjoyable. As with other mainstream foreign films, this can be attributed only to the mindless perpetuation of certain rules — not to any sort of common sense, much less a consensus.

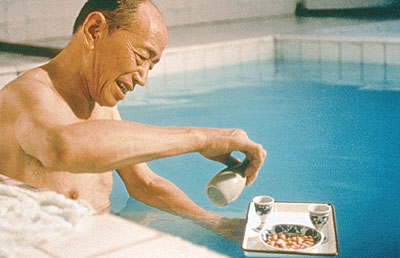

Da Ming (Pu Cun Xin), a well-to-do businessman from Shenzhen with a mobile phone, turns up at the traditional public bathhouse in Beijing run by his elderly father, Master Liu (Zhu Xu), and his mentally challenged younger brother, Er Ming (Jiang Wu), after a postcard with a drawing from Er Ming leads him to conclude, mistakenly, that his father has died. Da Ming is embarrassed about the bathhouse, which is proof of his humble origins, and somewhat alienated by most of the local clientele — the old men who stage battles between their pet crickets, the young, pudgy guy who likes to sing “O Sole Mio” at full blast under the shower — and he doesn’t plan to stay long. Then one day he lets his kid brother slip away and get lost in city traffic, and his father berates him for his negligence — leading to much worry until Er Ming finds his way home on his own. Da Ming is gradually won over to the therapeutic and communal virtues of the bathhouse — to which his father and brother are fully committed — and to their way of life in general, including the cheerful races they run in the neighborhood when they aren’t working….

There’s a lot more to Shower than this indicates. To start with, there’s the ease with which director Zhang Yang moves between reality and fantasy. The movie starts with a fantasy about an automated bathhouse of the future, a sort of dreamy car wash for humans — in contrast to a real car wash that crops up later in the movie — before settling into the homey, old-fashioned bathhouse that will serve as its main location and focus. The transition is extremely graceful, and subsequent fantasy interludes are introduced with similar deftness.

There’s also the charisma of Zhu Xu, recently seen in the title role of The King of Masks, as the amiable codger who runs the bathhouse and dispenses massages and wisdom — even sexual therapy in the case of a customer who can’t get it up and his angry wife. (How many mainstream American comedies deal with such problems?) He’s a wonderful actor, with some of the juiciness of Spencer Tracy and some of the placidity of Chishu Ryu, Yasujiro Ozu’s wiry patriarchal standby. Alas, the angry wife is just about the only female character we see much of in Shower, though there are a couple of references to Master Liu’s deceased wife, many phone conversations between Da Ming and his offscreen wife, and a group of women periodically shown dancing in a neighborhood park. This is basically an all-male story.

I’m not crazy about this film’s sentimentality. It observes the bathhouse, which is slated to close, with the kind of warmth and reverence given the small-town Texas movie house in The Last Picture Show, another boys’ movie that relies on a sweet-tempered, mentally challenged individual to tug at the heartstrings. However much such tear-jerking figures have been used in attempts to win Oscars, I don’t believe they mean the same thing or function in the same way in a Chinese context — just as I don’t believe that William Faulkner was being calculating when he used such a figure in The Sound and the Fury.

But just because I believe this doesn’t mean I’m right. Barbara Scharres, director of the Film Center and an astute specialist in Hong Kong movies, recently told me that mentally challenged figures are quite common in Hong Kong cinema — and not just as comic or sentimental types. For all I know, using such a character in a mainland Chinese feature these days may be every bit as crass and cynical as placing such a figure in a Hollywood feature. (For what it’s worth, Toronto film festival programmer Kay Armatage says that writer-director Zhang Yang and the four other writers he worked with come from China’s pop-music and underground music-video scene.) But even if this turned out to be true, we probably wouldn’t feel as manipulated; part of the freshness Western audiences see in Shower clearly derives from its relatively unfamiliar elements, most of which alter our perception of elements we find more familiar.

I find it touching, for instance, that even though the bathhouse is in Beijing, some non-Chinese reviewers have got confused and stated that it’s in the country, just as they’ve stated that the older brother comes from the big city. It’s an easy mistake to make, because what we see of Beijing in the film doesn’t correspond to our idea of big cities. (Similarly, in many Iranian films Tehran is often mistaken for the suburbs or sticks.) As an extension of the same principle, an undeniable part of the charm and fascination of a movie like Shower is that it gives us glimpses of everyday life in a part of the world we still know precious little about. I know this isn’t supposed to matter to suburbanites, but maybe a few of them can sneak off to Chicago and see this movie when Jack Valenti and his minions aren’t looking.