From the September 1, 1987 Chicago Reader. Criterion has released this film on a Blu-Ray with many extras. –J.R.

Try as he might, writer John Sayles has never been a natural filmmaker. But this sincere 1987 account of a coal miner strike and subsequent massacre in West Virginia in 1920 is so conscientiously detailed and so keenly felt and imagined — as well as attractively shot, by Haskell Wexler — that he deserves at the very least an A for effort. Simpleminded yet stirring, his depiction of a community of local whites, migrant blacks from the Deep South, and immigrant Italians gradually joining forces against the company bosses and their henchmen, under the leadership of a pacifist organizer, offers a bracing alternative to complacent right-wing as well as liberal claptrap. If Sayles’s bite were as lethal as his bark, he might have given this a harder edge and a stronger conclusion. But the performances are uniformly fine: Chris Cooper, Mary McDonnell, Kevin Tighe (perfect in dress and physiognomy, but strictly one-dimensional as scripted), James Earl Jones, and Sayles; the regional accents are especially well-handled. 133 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

This review of Other Voices, Other Rooms appeared in the February 13, 1998 issue of the Chicago Reader. I’m not positive that the second image I’ve used to represent Sokurov’s Oriental Elegy actually comes from that video and not from another Sokurov work, but it evokes my memory of that video so well that I hope I can be granted poetic license for this. — J.R.

Other Voices, Other Rooms

0 (worthless)

Directed by David Rocksavage

Written by Sara Flanigan and Rocksavage

With Lothaire Bluteau, Anna Thomson, David Speck, April Turner, and Frank Taylor.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

I cannot tell a lie: my first exposure to two great tragic novels, Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts (1933) and William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury (1929), was the dreadful Hollywood adaptations released during my teens, both of which had happy endings. As silly as these movies were — Vincent J. Donehue’s Lonelyhearts (1958) and Martin Ritt’s The Sound and the Fury (1959) — they piqued my interest in the original novels, and I discovered, among many other things, the blatant inadequacy of the movie versions.

The same thing could happen to a teenager attending the dreadful film adaptation of Truman Capote’s first published novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948) — not a novel of the same caliber as West’s and Faulkner’s, though still a work of real distinction, from his best period — but the odds are slim. Read more

Mia Farrow on Spielberg and Riefenstahl

I’m almost two weeks late in hearing about this, but I’m assuming other latecomers will be interested as well in the op-ed piece published by Mia Farrow and her son Ronan in the March 28 issue of the Wall Street Journal. Titled “The Genocide Olympics,” the Farrows’ article attacks Steven Spielberg for his friendliness in agreeing to help stage the Olympics ceremonies in Beijing, thereby implicitly putting some kind of seal of approval on China’s complicity in the Darfur genocide, which the Farrows have recently been observing firsthand. “Is Mr. Spielberg, who in 1994 founded the Shoah Foundation to record the testimony of survivors of the holocaust, aware that China is bankrolling Darfur’s genocide?” they ask. And a bit later: “Does Mr. Spielberg really want to go down in history as the Leni Riefenstahl of the Beijing Games?”

Various web sites have been having a field day with this, on the right [2014: this link, at http://www.libertyfilmfestival.com/libertas, has subsequently been removed] as well as the left. The right, of course, is taking particular pleasure in drawing attention to the hypocrisy of a liberal like Spielberg.

Read more

Commissioned by the Chicago Reader in late September 2016. — J.R.

The eponymous New Jersey town proves to be a hotbed of poetry and art in this comedy from writer-director Jim Jarmusch, thanks to his beautifully loony conceit that all ordinary Americans are closet poets and artists of one kind or another (even if they don’t always know it). The bus-driver hero (Adam Driver), also named Paterson, writes poetry, and his Iranian wife (actress and rock musician Golshifteh Farahani) goes in for black-and-white domestic design; they know they’re artists and are completely smitten with one another, but their neighbors in a local bar seem less fortunate. Like many of Jarmusch’s best films, this keeps surprising us with its minimal, witty inflections, at once epic and small-scale, inspired in this case by the book-length poem Paterson by William Carlos Williams. (Jonathan Rosenbaum)

Read more

Read more

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8yr8hEyFYcg

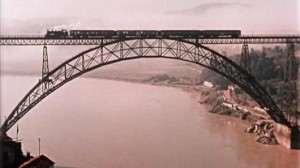

The Portuguese title of this beautiful, wordless 15-minute documentary means “One Century of Power,” and the black and white footage comes from one of his earliest films, Hulha Branca (1932). [7/8/15]

Read more

Read more

A Critic’s Choice from the April 9, 1999 Chicago Reader. Seeing Luigi Zampa’s wonderful To Live in Peace (1947) yesterday, for the first time, at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna, I discovered the same theme attached to an earlier and more “popular” war, expressed largely in comic and even farcical terms. — J.R.

Essential viewing. This documentary about a group of American and Vietnamese war veterans, many of them disabled, bicycling 1,200 miles from Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City is many things at once — act of witness, account of a multicultural exchange, sports story, journalistic investigation, and mourning for the devastation of war. Ultimately it may be too many things to yield a cumulative effect, yet its scenes of former soldiers struggling with the meaning of the war are the most moving ones on the subject since Winter Soldier (a wartime agitprop film in which Vietnam veterans confessed their “war crimes”). The corporate sponsorship of the bicycle marathon adds many ironic layers, but the emotional encounters it permitted seem more important than anything else I’ve seen about our involvement in Vietnam. Coproduced by Chicago’s Kartemquin Films and directed by Jerry Blumenthal, Gordon Quinn, and Peter Gilbert (Hoop Dreams). Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 1, 1993). — J.R.

One of the craftiest and most satisfying pieces about gender politics to come along in ages (1993) — all the more crafty because audiences are encouraged to see it simply as a movie about a seven-year-old chess genius, based on Fred Waitzkin’s nonfiction book about his son Josh. Very well played (with Max Pomeranc especially good as Josh), shot (by Conrad Hall), and written and directed (by Steven Zaillian, who also scripted Schindler’s List), it gradually evolves into a kind of parable about how a gifted kid learns to choose his role models and choose what he needs from them. The part played by gender in all this is both subtle and complex, relating not only to chess strategy (e.g., when to bring your queen out) and the personality of Bobby Fischer, but also to the varying attitudes toward competition taken by his parents (Joe Mantegna and Joan Allen) and two teachers (Laurence Fishburne and Ben Kingsley). It makes for a good old-fashioned inspirational story, absorbing and pointed. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 2002). — J.R.

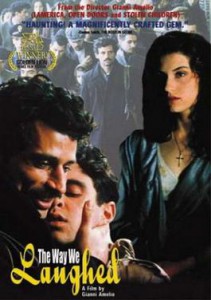

Winner of the Golden Lion at the Venice film festival, this 1998 feature by Gianni Amelio (Stolen Children, Lamerica) wears its art, as well as its heart, on its sleeveso much so that I feel guilty for not liking it more. It explores the idealized love of an illiterate Sicilian worker (Enrico Lo Verso, who has the eyes of a rain-soaked basset hound) for his literate kid brother (Francesco Giuffrida) after they immigrate to Turin, but that love is supposed to spell out the meaning of his entire life, with other details (work, parents, wife and kids) made to seem strictly incidental. The same sense of hyperbole extends to Amelio’s arty and gloomy evocations of the period (1958-’64), though the literary way this is split up into six sections, each focusing on a single day and bearing its own one-word title, is rather elegant. In Italian with subtitles. 128 minutes. (JR) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 30, 2002). For the record, Fritz Lang’s line in Contempt about CinemaScope being appropriate only for snakes and funerals is a misattribution of a wisecrack that actually came from Orson Welles.– J.R.

Fritz Lang’s only film in CinemaScope (1955, 89 min.) is one of his most neglected features, at least in this country. (In France there’s a deluxe edition on DVD made especially for high school students.) A kind of 18th-century fairy tale about an orphan (Jon Whiteley) in Dorset who’s adopted, after a fashion, by a smuggler (Stewart Granger), this classy MGM production was adapted from a novel by J. Meade Faulkner by Margaret Fitts and Jan Lustig, and its dreamlike sense of wonder is equaled only in Lang’s German pictures. John Houseman produced, and Mikos Rozsa wrote the stirring score; the fine secondary cast includes George Sanders, Joan Greenwood, and Viveca Lindfors. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 2002). — J.R.

I saw this French mystery thriller, the first feature of writer-director Gilles Mimouni, shortly after its 1996 release, and it left little residue. However, it has Romane Bohringer (Savage Nights), and that’s definitely a plus. Just before leaving Paris for Tokyo, the hero (Vincent Cassel), who’s engaged, thinks he spots an old flame (Monica Bellucci) in a cafe. He becomes obsessed with seeing her again, finds out where she lives, and hides out in her apartment — though he winds up having sex with Bohringer instead. In French with subtitles. 116 min. (JR) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 5, 2003). Criterion has released a Blu-Ray of this film. P.S. If you hit and load the second and third illustrations below, you can see them move slightly. — J.R.

I only recently caught up with Jaromil Jires’s overripe 1970 exercise in Prague School surrealism, now that it’s become available again, and I’m miffed that I had to wait so long. The 13-year-old title heroine, who’s just had her first period, traipses through a shifting landscape of sensuous, anticlerical, and vaguely medieval fantasy-horror enchantments that register more as a collection of dream adventures, spurred by guiltless and polysexual eroticism, than as a conventional narrative. Virtually every shot is a knockout — for comparable use of color, you’d have to turn to some of Vera Chytilova’s extravaganzas of the same period, such as Daisies and Fruit of Paradise. If you aren’t too anxious about decoding what all this means, you’re likely to be entranced. In Czech with subtitles; a 35-millimeter print will be shown. 77 min. Gene Siskel Film Center.

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 21, 2003). — J.R.

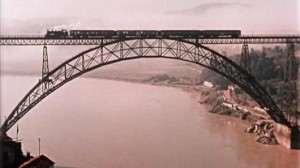

Manoel de Oliveira’s 2001 masterpiece explores the Portuguese city where he’s lived for more than 90 years, though it concentrates on the first 30 or so, suggesting that his childhood must have lasted a very long time. It’s a remarkable film for its effortless freedom and grace in passing between past and present, fiction and nonfiction, staged performance and archival footage (including clips from two of his earliest films, Hard Work on the River Douro and Aniki-Bobo) while integrating and sometimes even synthesizing these modes. He’s mainly interested in key images, music, and locations from the Eden of his privileged youth, and some of the film’s songs are performed by him or his wife — though we also get a fully orchestrated version of Emmanuel Nunes’s Nachtmusik 1. In Portuguese with subtitles. 61 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

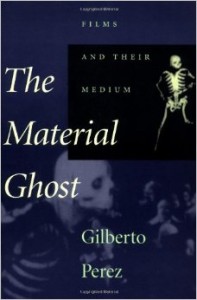

I can’t remember the first time I met Gil Perez, but the first time I got in touch with him, which must have been in the late 60s, it was to reprint a remarkable essay of his about Murnau that had appeared in Sight and Sound for an anthology I was editing called Film Masters, a book that for various complex reasons never came out (although, if memory serves, it twice reached the galley-proof stage). I do recall that Gil was still a theoretical physicist at the time, in the U.S. but still relatively fresh from Havana, and he was most likely making his academic transition to film studies and film theory when we eventually met in New York. (See his Introduction to his magisterial 1998 The Material Ghost, “Film and Physics,” for more details.) Years later, circa the early 80s, we became neighbors in Hoboken, living only a few blocks apart, and we remained loosely in touch for the remainder of his life, during his various stints at William Paterson, Princeton, Harvard, Missouri, and, most permanently, Sarah Lawrence, where he ran the film history program.

A slow and methodical writer, but also a prolific one, Gil wrote frequently about film for the The Hudson Review, The Yale Review, and the London Review of Books and less often for film and academic journals, and I was often envious of the way he was both welcome and able to hold his own as a public intellectual with a literary sensibility in those and similar venues, such as The Nation. Read more

Written for the Fall 2015 issue of Film Quarterly. — J.R.

The Writers: A History of American Screenwriters and

Their Guild by Miranda J. Banks

This is clearly a creditable, conscientious, intelligent, and

useful book, but I feel obliged to confess at the outset that

I don’t feel like I’m one of its ideal or intended readers. The

subtitle loosely describes its contents, but “A Business

History of Hollywood Screenwriters and Their Guild”

would come much closer to the mark, even if it might make

the book less marketable to me and some others. And the

unexceptional simplification of the title and subtitle is part of

what gives me some trouble: it’s the business of Hollywood,

after all, to convince the public that “American screenwriters”

and “Hollywood screenwriters” amount to the same

thing. And the moment that any meaningful distinction

between the two collapses, then the studios, one might argue,

have already won the battle.

I don’t expect my own bias about this matter to be shared

by many of Film Quarterly’s readers. Writers who blithely

and uncritically toss about terms like “Indiewood” designed

to further mystify the differences between studio work and

independent work probably don’t think they’re working for

the fat cats, but from my vantage point as a journalist who

thinks that these distinctions deeply matter, they’re the worst

kind of unpaid publicists. Read more

I’m very glad that I recently purchased Saul Bellow’s collected nonfiction — a handsome, interesting, and useful book, even if I tend to regard Bellow as the most overrated of all the “major” contemporary American novelists (certainly talented and smart, but not terribly interesting when it comes to formal inventiveness). And among the many valuable discoveries to be made here is the fact that Bellow served as a film critic for the magazine Horizon in 1962-1963, a stint which yielded four separate columns — on Morris Engels’ Lovers and Lollipops, on Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana, and two think pieces, “The Mass-Produced Insight” (which quotes from his pal Manny Farber) and “Adrift on a Sea of Gore” (mostly about Richard Fleischer’s Barrabas).

I’m very glad that I recently purchased Saul Bellow’s collected nonfiction — a handsome, interesting, and useful book, even if I tend to regard Bellow as the most overrated of all the “major” contemporary American novelists (certainly talented and smart, but not terribly interesting when it comes to formal inventiveness). And among the many valuable discoveries to be made here is the fact that Bellow served as a film critic for the magazine Horizon in 1962-1963, a stint which yielded four separate columns — on Morris Engels’ Lovers and Lollipops, on Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana, and two think pieces, “The Mass-Produced Insight” (which quotes from his pal Manny Farber) and “Adrift on a Sea of Gore” (mostly about Richard Fleischer’s Barrabas).

I was especially interested in Bellow’s appreciative remarks about Buñuel. But here is where the attentions of his otherwise careful editor, Benjamin Taylor, come up woefully short. Listing some of the more notable items in Buñuel’s filmography, Bellow comes up with two very puzzling titles, The Roots (1957) [sic] and Stranger in the Room (1961) [sic]. The second of these, which he discusses in some detail, sounds like he might be thinking of La Fièvre Monte à El Pao (1959), while the first is most likely La Mort en Ce Jardin (1956). Read more