From Monthly Film Bulletin No. 507, April 1976. –- J.R.

The Man Who Fell To Earth

Great Britain, 1976 Director: Nicolas Roeg

A stranger from another planet lands in New Mexico; calling himself Thomas Jerome Newton, he sells a series of rings to various jewellery stores and soon amasses a small fortune. He approaches Oliver Farnsworth, a homosexual lawyer in New York specializing in patents, shows him his plans for nine inventions destined to transform the communications industry, and concludes an agreement whereby Farnsworth supervises Newton’s World Enterprises Corporation and communicates with Newton, who wishes to maintain his privacy, chiefly by phone. Dr. Nathan Bryce, a chemical engineering professor, becomes intrigued by the corporation and decides to learn more about its master-mind. When Newton faints in an elevator, unaccustomed to the acceleration, the attendant, Mary-Lou, nurses him back to health and becomes his lover, tempting him into a taste for gin. After building a house on the lake where he landed and inaugurating a private space program, Newton hires Bryce as a consultant, and the latter discovers with a hidden X-ray camera that Newton s metabolism is not human. Newton intimates that he came to Earth because his race was dying from a lack of water and that his space program is designed to return him to his wife and children. Read more

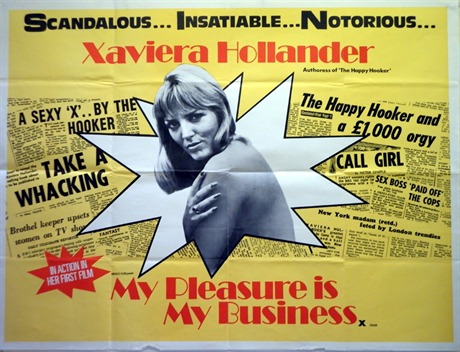

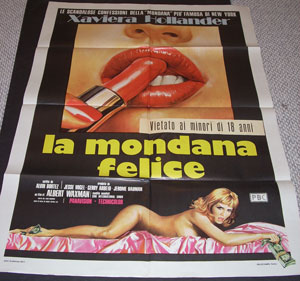

From Monthly Film Bulletin, April 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 495). — J.R.

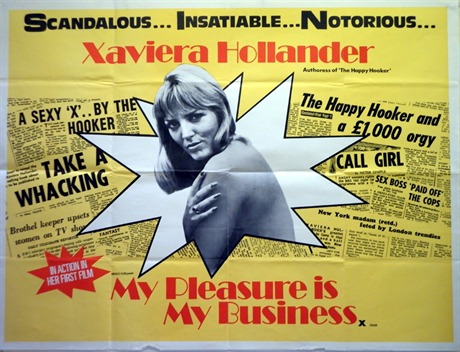

My Pleasure Is My Business

Canada, 1974 Director: Albert S. Waxman

Deported from America by a U.S. senator who wants to keep her

away from his son-in-law, Gabrielle, a promiscuous movie star and

sexual liberationist, is flown to the country of Gestalt. After

confering with his aides, the corrupt Prime Minister decides to admit her

into the country, thereby hoping to deflect some of the charges of

immorality laid against the government. Gabrielle is accorded a

luxurious suite by a North African hotel manager in exchange for

the promise of sexual favors, and applies for a job as sexual

therapist with pudgy psychiatrist Freda Schloss, who turns out to

want the therapy herself. While the Prime Minister and his

henchmen plot ways-of arresting her for prostitution,

Gabrielle picks up an artist in a cafe and makes love with

him in his flat, looks up an old French girlfriend who acts

in porn films (along with the local police chief), and attends

a wild costume party given by another old friend. Cornered

by the police when she returns to her hotel, Gabrielle

persuades them to drop the charges by reminding the

police chief of his skin-flick activity. Read more

From American Film (July-August 1979). Incidentally, Criterion’s recent Blu-Ray of Ugetsu is ravishing, regardless of what Burch says (or, rather, doesn’t say).– J.R.

To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in the Japanese Cinema by Noël Burch. Revised and edited by Annette Michelson. University of California Press, $19.50.

The most ambitious and detailed study of Japanese cinema since Joseph L. Anderson and Donald Richie’s pioneering history appeared twenty years ago, Noël Burch’s To the Distant Observer adopts an overall approach that is radically different from that of its predecessor. Modernist and materialist in orientation where other critics have been realist and transcendental, Burch argues for a nearly total revision of the way we perceive Japanese film — proposing a new set of criteria as well as an alternate canon of masterpieces.

To call his book controversial would almost be an understatement. Copies of a draft were circulated among a few film scholars in London more than four years ago, sparking a heated debate that has raged ever since. For Burch is arguing that “the most fruitful, original period” the Japanese film history coincided with the years between 1934 and 1943, when the Japanese people embraced “a national ideology akin to European fascism”. Read more

This originally appeared in the January 10, 2001 issue of the Chicago Reader. It seems worth reprinting as a kind of adjunct to my overview piece about Oshima, written for Artforum in 2008 and also available on this site. –J.R.

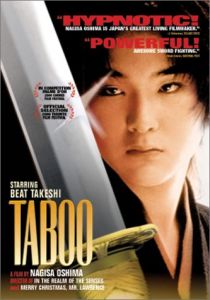

Taboo

****

Directed and written by Nagisa Oshima

With Beat Takeshi (Takeshi Kitano), Ryuhei Matsuda, Shinji Takeda, Tadanobu Asano, and Yoichi Sai.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Mark your calendars. Over the next six weeks, the Music Box is offering three eye-popping masterpieces from Asia. This is a welcome sign–-as is the popularity of the breezy Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon in the multiplexes–-that American theaters and audiences are finally recognizing that a lot of the best movies come from the other side of the planet and that there’s as much diversity among them as there is among ours.

Yi Yi, which opens March 2, is a three-hour feature set in contemporary Taiwan. It was just voted best picture of the year by the National Society of Film Critics, the first foreign-language picture to receive this honor since Akira Kurosawa’s Ran 15 years ago. Its writer-director, Edward Yang, is one of the two or three undisputed masters of Taiwanese cinema, and the Film Center gave us a full retrospective of his work in 1997. Read more

I am reprinting the entirety of my first and most ambitious book (Moving Places: A Life at the Movies, New York: Harper & Row, 1980) in its second edition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995) on this site in eleven installments. This is the tenth.

Note: The book can be purchased on Amazon here, and accessed online in its entirety here. — J.R.

5—

Made in Hoboken

Douglas, Wyoming, 1914—three states away from where our old friend Gordon MacRae is still only a radical freshman or a freethinking sophomore at the University of Indiana—Bo is operating his very first movie theater, at the age of twenty-seven. Think of it: when Jonathan’s the same age, in 1970, he’s working fitfully on his second yet-to-be unpublished novel, completing his first yet-to-be unpublished book as an editor (a collection of film criticism he was commissioned to do), still living on the dregs of Bo’s inheritance, and dividing the first three months of the year among three countries: pursuing a heavy love affair in New York, having his appendix removed in London (and smoking hash with his brother Michael’s friends in a room called the Box), and taking acid all alone one beautiful spring afternoon in Paris, where he moved last fall, acid that suddenly prompts him to buy red paint, a roller, and brushes, and to go to work on his bedroom closets—a conversation with the wood, red saying one thing, grain saying another—and later sends him out the door and up rue Mazarine to the Odéon métro stop, a little after 6:30, to take the Porte de Clignancourt train as far as Châtelet and then the Mairie des Lilas train to République. Read more

This was published at the end of my first year at the Reader, in their Christmas issue. –J.R.

BROADCAST NEWS *** (A must-see)

Directed and written by James L. Brooks

With Holly Hunter, Albert Brooks, William Hurt, Robert Prosky, Lois Chiles, Joan Cusack, and Jack Nicholson.

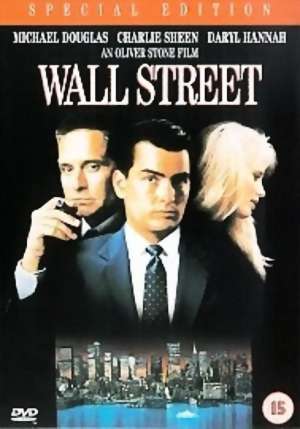

WALL STREET ** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Oliver Stone

Written by Stone and Stanley Weiser

With Charlie Sheen, Michael Douglas, Martin Sheen, Daryl Hannah, Terence Stamp, Hal Holbrook, and Sylvia Miles.

Both Broadcast News and Wall Street score as punchy, energetic movies that are designed to feel as contemporary as possible without taking place in the literal present, and both pivot around a moral reckoning that accompanies economic cutbacks -– as if to remind us that this country’s Reagan-inspired spending spree, which tripled our trillion-dollar national debt, seems to be drawing to a fearful close. Apart from offering behind-the-scenes glimpses of their all-encompassing, hothouse professional turfs, both movies are built around the mise en scene of a moral crisis that splits the major characters apart –- each one charting a mutual seduction that leads to recriminations and the characters isolated in opposing moral camps. Yet the undisputed effectiveness of these films as entertainment seems at least partially predicated on fudging or at least mystifying the moral issues that they are bold enough to raise. Read more