From Monthly Film Bulletin, April 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 495). — J.R.

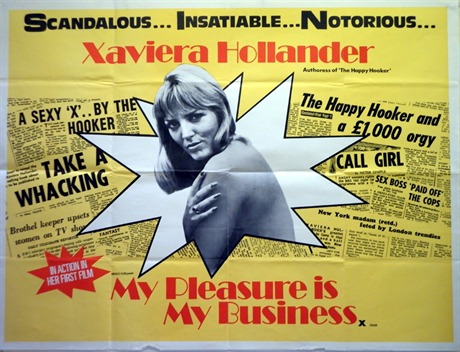

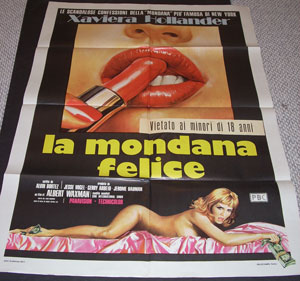

My Pleasure Is My Business

Canada, 1974 Director: Albert S. Waxman

Deported from America by a U.S. senator who wants to keep her

away from his son-in-law, Gabrielle, a promiscuous movie star and

sexual liberationist, is flown to the country of Gestalt. After

confering with his aides, the corrupt Prime Minister decides to admit her

into the country, thereby hoping to deflect some of the charges of

immorality laid against the government. Gabrielle is accorded a

luxurious suite by a North African hotel manager in exchange for

the promise of sexual favors, and applies for a job as sexual

therapist with pudgy psychiatrist Freda Schloss, who turns out to

want the therapy herself. While the Prime Minister and his

henchmen plot ways-of arresting her for prostitution,

Gabrielle picks up an artist in a cafe and makes love with

him in his flat, looks up an old French girlfriend who acts

in porn films (along with the local police chief), and attends

a wild costume party given by another old friend. Cornered

by the police when she returns to her hotel, Gabrielle

persuades them to drop the charges by reminding the

police chief of his skin-flick activity. After a subsequent police

chase, she appears on local television to express her liberal views on

masturbation, enraging the Prime Minister, who orders an immediate

arrest; but the police who raid her room find the Minister’s wife

there in bed with another man. Triumphant, Gabrielle and all her

friends enter the Minister’s house to continue their sexual frolics.

Surrounded by consistently unfunny actors indulging in knockabout

slapstick so overdirected that it almost makes Mel Brooks look

like Robert Bresson, Xaviera Hollander — the ex-prostitute authoress

whose reputation this film is built round — displays a surprising

amount of poise and assurance. It may be that prostitution itself

provides a fair measure of acting experience; whatever the reason,

Hollander manages to hold her own in a vulgar farce where

practically everyone else is straining painfully for effects. The

nonsensical, slapdash plot seems little more than a stab at emulating

What’s New, Pussycat? (with “Dr. Schloss”, for instance, assuming

the Peter Sellers part), and despite a reasonable amount of high

spirits, the shrill ugliness and witlessness of the Gestalt cabinet

scenes are sufficient to sink this shaky vehicle without a trace.

Before it vanishes, however, Hollander’s italicized star treatment —

remotely akin to Frank Tashlin’s celebration of Jayne Mansfield,

and Mae West’s delivery of one-liners (without the lines) — affords

the actress some opportunity to do justice to the movie’s modest

thesis: that simple relaxation in the midst of hysteria is a desirable

achievement.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM