From American Film (October 1979). -– J.R.

The actors playing Chuckie and Mikey, a sinister vaudeville team dressed in matching tuxedos, top hats, and capes, are pretending to walk toward the camera. They move their feet without advancing anywhere. Behind them, a gigantic black-and-white blowup of a garden at Versailles, mounted on a platform, is slowly rolled away to further the partial illusion. Then they turn around and pretend to walk away from the camera, and the Versailles backdrop is slowly wheeled toward them. All this time the characters discuss a woman they have killed in Budapest.

“Think of it, ” Mikey says wistfully in a Russian accent. “I could have married a princess. ”

“All bourgeois dreams end the same way,’’ Chuckie replies in a disdainful tone. ”Marry royalty and escape.”

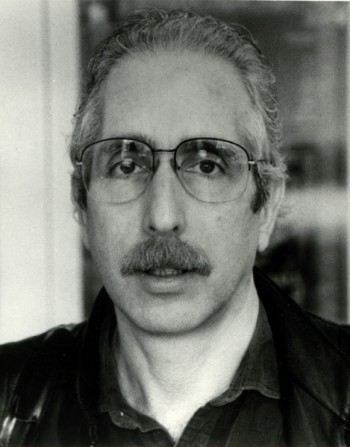

“OK, cut!” says Mark Rappaport, concluding the fifth and final take.

It’s the first day of shooting on Impostors, a macabre comedy by the Brooklyn-born independent filmmaker. The movie, Rappaport’s fifth feature, is being shot in his loft in the SoHo section of Manhattan, and spirits are running high. A young crew of about twenty persons — fifteen of them on the regular payroll — are clustered on one side of the loft. The scattered arsenal of lighting and sound equipment makes the space look like a fair facsimile of a studio sound stage. A few yards away, attached to the door of Rappaport’s refrigerator, are the cautionary words of Douglas Sirk: “A director’s philosophy is lighting and camera angles.”

Rappaport moved into the loft a few years ago so he could shoot his second feature, Mozart in Love, under the skylight. “There are a hundred amps here, floors to do tracking on, and places to hang lights,” he says. “Of course, I want to get out of this ‘My apartment is my studio is my life’ thing, but I do want to keep this scale.”

***

Finding the right classification for Rappaport’s movies is no easy matter. He neither claims nor is commonly assigned the avant-garde label — unlike his SoHo neighbors Richard Foreman and Yvonne Rainer. But that doesn’t mean that his films necessarily fall into the commercial category, either. Last May, accepting a SoHo Weekly News arts award for “best art direction in a commercial movie,” he wryly remarked that by no stretch of the imagination could The Scenic Route, after totally bombing at the box office, be considered “commercial.”

But despite some vexing, ongoing worries , 1979 may be a bumper year for the thirty-seven-year-old filmmaker. One Sunday night in February, The Scenic Route was broadcast on WNET in New York. In one fell swoop, he acquired more American viewers than all his other films combined ever had.

Around the same time, the British Film Institute selected The Scenic Route as “the most original and imaginative film of I978” — an award that in previous years has gone to such directors as Michelangelo Antonioni, Robert Bresson, and Rainer Werner Fassbinder. And early this summer — with loans, promises of support from German and French television, and hopes of some future backers — Rappaport began shooting Impostors.

The estimated budget of Impostors was $115,000. That’s three times the budget of The Scenic Route and about seventeen times that of his first feature, Casual Relations, made in 1973. But it’s still minuscule compared even to a low-budget Hollywood production.

“When it’s a low-budget film, the cast and crew are paying the price on the other end, ” says Rappaport. “I have some really great actors in my new film, who are ayailable because the Screen Actors Guild was very generous in making a deal with me.” Some of the actors are theater people who haven’t been in films before. “So I’m very lucky — I got a lot of people at the right time, at the right stages in their careers.”

Rappaport discovered that “this is a blade which can cut two ways. One of the actors, Peter Evans — who appeared in Streamers and A Life in the Theatre on stage — landed a juicy part in a television movie, and the shooting schedule of Impostors had to be reshuffled in order to accommodate his absence in June. Money was a continuing problem . “I’m trying to raise money at the same time that I’m trying to coordinate, produce, and direct the film, and it’s madness. I intend to whine, beg, borrow, and steal — notice which comes first — and I’m going to borrow against the moneys that are promised for later. People have been incredibly generous: I’m getting deferments at the lab, deferments for camera equipment, and stuff like that.”

Only recently has Rappaport’s name been able to inspire this much financial confidence. Casual Relations, for example, was shot piecemeal over a year and a half and paid for exclusively out of his own pocket from his jobs as a film editor. Looser in narrative structure than his subsequent films, Casual Relations is very rich in movie lore — the kind of explicit and loving references that can only come from a veteran, compulsive moviegoer.

The film is also a kind of clearinghouse for Rappaport’s most persistent concerns: One finds melodramatic, high-style fantasies about upper-class romance threatened by violence, deceptions, and betrayals. One also finds a verbal style of deadpan irony — a style of wit discernible in Rappaport’s own speech. It has prompted certain spectators to compare his films to Woody Allen’s.

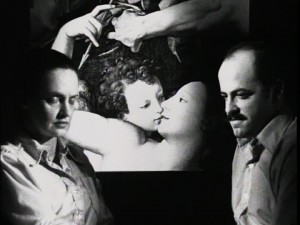

The referential aspect becomes somewhat more subdued in Mozart in Love — made two years later thanks to an editing job, the sale of Casual Relations to German television, and a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts. Mozart in Love offers virtually an equivalent to a guided gallery tour of singing paintings, each one elegantly composed.

My favorite Rappaport movie to date, Local Color, introduces the figures of twins –also central to Impostors. More intensely melodramatic in plot than his preceding work, the film has no less than eight central characters. A loaded gun surreptitiously changes hands among several of them, rather like the earrings in Max Ophüls’ Madame de…, which, along with Luchino Visconti’s Senso, is Rappaport’s favorite movie.

***

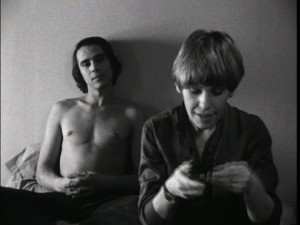

In Impostors, Chuckie is played by Charles Ludlam, founder of the celebrated Ridiculous Theatrical Company and a superb mimic, continually trying on fresh faces, voices, and stances. Mikey is played by Michael Burg. He performed in the original off-Broadway production of The Passion of Dracula for a year and a half, and he is proving to be an effective partner in this unusual black comedy team.

A note on the characters Chuckie and Mikey in Rappaport’s script — written with Ludlam and Burg expressly in mind — specifies that their constantly shifting relationship “must be played like an amalgam of the Marx Brothers and Peter Lorre, the Three Stooges mixed with Dostoevski. There is also a broad streak of amiable Mel Brooks vulgarity running through it. In short, they are always playacting But underlying it all is a menacing dead seriousness that is unsettling — two psychopaths, refugees from trashy horror films, on the loose.”

After everyone breaks for lunch, the Versailles backdrop is turned around so that a painted photograph of a multi-columned English art deco building on the reverse side can be used in the next shot. The same actors are now dressed in trench coats and Stetsons like forties detectives, and Rappaport, a viewfinder around his neck, positions them facing left.

Cameraman Fred Murphy — who shot Girl Friends as well as the last two Rappaport features — has already lighted the set, and the actors are clearly finding it hot under the flood lamps as last-minute adjustments are being made.

“Let’ s boogie,” Rappaport says.

In this shot, Chuckie and Mikey appear to be discussing more recent murder victims. Once again, the background creates an odd, dreamlike effect.

“Why did they act so mysterious when I asked about the golden scarab?” Chuckie mutters irritably, rolling his eyes. “And all that phony Egyptian-style furniture. All those pretenses of being elusive. It was their fault.” Mikey agrees.

Chuckie says that he won’t deal with amateurs any more. “You and me both,” Mikey replies. With a snarl full of clenched teeth, Chuckie turns on him and hisses, “I’m talking about you, too, knucklehead!” Delivered with a sharp finger-stabbing gesture at Mikey’s chest, it’s a line that irresistibly evokes early James Cagney.

If the references to royalty conjure up quasi-literary European fantasies, it’s worth noting that Rappaport, while at Brooklyn College, had a special interest in the Victorian novel. But it may have been his enthusiasm for European art cinema that encouraged him to abandon a graduate school scholarship in literature at New York University and to concentrate on film instead. In f act, he had already dropped out of college once in the early sixties and worked for Radley Metzger, the porn director, who was then turning out trailers for Janus Films.

After Chuckie and Mikey’s scene in trench coats, the rest of the day is spent on a difficult shot without sound in which Lina Todd, playing a girl named Gina, looks into two mirrors successively on facing walls. One difficulty is placing the camera so that it can’t be seen in either mirror. The solution? To drill a hole through one wall so the camera can peer through and to disguise it with an arrangement of gladiolas next to the opposite mirror.

When I stop by Rappaport’s loft the next day, he is using, quite effectively, a method of front projection recently employed in Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s celebrated seven-hour film, Our Hitler: A Film From Germany. The color slide being projected shows the illuminated auditorium of an Italian opera house. Posed in the foreground in a romantic embrace are Mikey and Tina, played by Ellen McElduff, who is dressed in khaki slacks and a lavender blouse. A member of the Mabou Mines experimental theater group, McElduff won an Obie this year for her performance in Southern Exposure. In Impostors she figures as an assistant in Mikey and Chuckie’s magic act a mysterious woman who has been seeing the hero, Peter, a handsome, wealthy playboy played by Peter Evans.

“Come with me. We’ll run away together,” Mikey says to her excitedly, his face partly in shadow. “I’ll ditch my faggot. You ditch yours. We’ll do the things all normal people do. . We’ll fall in love. We’ll screw like lunatics-at the beginning, anyway. We’ll get bored with each other. We’ll get on each other’s nerves . We’ll use each other’s toothbrush — but that won’t be the worst of it, by any means. . .”

Tina appears to respond positively until he gets to the toothbrush. Then her bright expression suddenly drops — a reaction that isn’t in the script, but one that Rappaport, crouched below the camera, has just asked McElduff to project. It gives the scene an extra touch of absurdity, and McElduff brings it off adroitly.

“Sounds good,” Tina finally replies. “But give me time to breathe. You exhaust me with the audacity of your scheme. ” After a pause, she continues, “No. I’ll stick with Peter for now. Even if it turns out the same way, the odds are better with a romantic than with a cynic. ”

“Coward,” Mikey almost whispers in chilly contempt, ending the take.

***

“Finance always has a determining role in the aesthetics of low-budget films, ” Rappaport told an interviewer last year. “In fact, it becomes a ‘political’ phenomenon: The money available influences low-budget filmmakers in countless ways. It determines the way they conceive their films, the way they structure, edit, and shoot them.” And money seems to be dictating a lot of Impostors, from the class consciousness in the dialogue to the old-fashioned craft of the special effects. As for the plot, Rappaport points out that it can be purchased on any street corner. From one point of view, taste and irony may be poverty’s best defenses against a conspicuous lack of wealth.

Film editing — virtually a science in how to be economical — is largely at the root of Rappaport’s approach to directing. “From editing I learned how much in directing is totally fake,” he says. “And since Casual Relations, I use as little editing as possible, because I know the more you can get a scene to work with the least editing, the more you’re really in control of the situation.”

The entire second week of shooting on Impostors was done on location at Entermedia, a former legitimate theater on the Lower East Side. Here the crew proceeded to work on scenes in cramped dressing rooms, on the stage, in the balcony, and inside a cozy cabaret fashioned out of a snack-bar lounge in the basement.

But toward the middle of the week, Rappaport suddenly had to face a serious financial crisis: Funds he had anticipated from French television hadn’t materialized, and most of the $50,000 promised by German television was available only for postproduction. Then, only a day or two before shooting would have had to be discontinued, an American investor from Chicago arrived on the scene with $25,000, saving the day.

In return for the $50,000 from Germany, Impostors will be screened twice on German television. “People say to me, ‘You got a grant from German television,'” Rappaport remarks, “and I say, ‘No, it isn’t charity, it’s business.’ But it’s so little business, it might as well be charity. For the kind of money that German television is giving, all you can make is these intimate little dramas, like people sitting around in their sweat shirts complaining to each other. “

Although Rappaport claims to have no interest in making big-budget Hollywood films, it’s clear that they are among his favorite films. “Let’s face it. Hitchcock is the most avant-garde director to this minute. He’s done things that nobody else would dare do.”

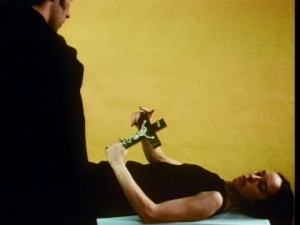

As if to bear out Rappaport’s statement that “the real riches in movies are in commercial films” because “richness always has to do with money,” the first scene that I see being prepared at Entermedia is almost an homage to some of Hollywood’s gaudier and more lurid fantasies. It consists of Chuckie and Mikey’s magic act onstage, in which they shut a willing Tina inside an upright pseudo-Egyptian sarcophagus and proceed to shove five swords through it.

The setting for this magic act, put together by scenic designer Bob Edmonds, certainly conveys a kind of splendor. There’s a backdrop depicting the Nile and one of the Pyramids in lush blue, green, and yellow tones that reminds me of Walt Disney’s Saludos Amigos; a full-size sphinx made out of Styrofoam; and the sarcophagus itself, whose lid is illustrated with a woman dressed in a bright red and orange costume. Cecil B. DeMille himself probably couldn’t have conceived of anything more delectably monstrous.

While Rappaport is off shooting a scene with Peter and Gina in a dressing room upstairs, another part of the production crew is assembling sections of the cabaret in the basement-where circus acrobats and an all-female rock group will late appear. Meanwhile, Ludlam, Burg, and McElduff assemble onstage to run through what will be shot tomorrow.

The men sing, dance, and clown around a good deal, rather like musicians when they’re tuning up. In imitation of a Toshiro Mifune samurai, Burg slashes through a stray chip of Styrofoam; Ludlam practices a soft-shoe routine. When McElduff arrives in her Egyptian costume -– “a cross between that of a belly dancer and Elizabeth Taylor’s leftovers from Cleopatra,” says the script — they’re all set to go.

A day later, with the camera mounted on tracks running down the right aisle, filming of the intricate act begins. McElduff steps into the open sarcophagus and, hands folded across her chest, assumes a sudden, wide-eyed Betty Boop expression as the lid is closed. An actress who has performed in many Samuel Beckett plays, she tends to save her best comic effects and then use them minimally, for maximum effect — in striking contrast to the jazzier, scattershot comic technique of Ludlam, who always goes for broke. Once inside the sarcophagus, McElduff escapes through a secret panel in back, while Ludlam and Burg thrust swords through the coffin.

By the middle of the week, the crew has fallen two scenes behind schedule. This will mean late hours for everyone, as Entermedia can be used only through the following Monday. But spirits are still fairly high, and for the actors and most of the crew, the world outside is starting to become rather abstract.

For the last shot I watch, Ludlam appears on the stage in a Mickey and Minnie Mouse T-shirt and white undershorts speckled with red hearts. He mutters, “This is what I get for being an admirer of Josef von Sternberg.” Seated behind the camera on the tracks, Rappaport says, “Charles, show the T-shirt for the college team!”

Ludlam adjusts his position. “What’s gonna sell more popcorn,” he asks, “me or the T-shirt?”

‘”It’ s not a question of popcorn.” Rappaport says . “It’s a question of espresso… ambrosia…granola cookies. “

***

What kind of distribution does Rappaport hope to get for Impostors?”I’m not going to find a distributor in America, ” he says flatly. “It’s not gonna happen.” Although an art gallery, Castelli-Sonnabend, has been handling his first two features — along with films by Yvonne Rainer, Richard Serra, and Michael Snow — he estimates he got “two-and-a-half rentals” in the past three or four years.

“Maybe something can happen with the Film Fund, ” he adds hopefully. “This group is forming that wants to put together a package of films that other distributors find too difficult and distribute the package themselves. ”

It’s impossible to guess how an audience will respond to the completed Impostors. It’s hard enough to know how to respond to the parts I see being shot. Some are very funny, yet they may wind up looking sinister on the screen. Some are downright disturbing, and I wonder whether they’ll strike anyone as comic. The delicate tightrope crossed in any Rappaport film seems to be stretched over a principle of uncertainty.

It’s an uncertainty relating to such matters as sexuality and sincerity — as well as what one might call the emotional authenticity of the characters. Are the impostors in the plot Chuckie and Mikey, or Gina and Tina, or Peter? More plausibly, do all five of them fit the bill? And what about Rappaport himself? Is he a true independent or a pretender to the Hollywood throne? “We are what we pretend to be,” Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., offers as a moral in his novel Mother Night, “so we must be careful about what we pretend to be. ”

Rappaport’s movies encourage us to think about our pretenses and fantasies. In this respect, as he puts it, they’re dramas that are funny rather than comedies pure and simple. How important will Impostors be? It’s hard to say. I suspect that, at the very least, it’ll be pretty interesting, and funny, and easy on the eyes. If the fates are kind, you might get a chance to see for yourself.

Jonathan Rosenbaum translated Orson Welles: A Critical View by André Bazin. He is working on a “critical memoir, “ Moving Places.