From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1977. — J.R.

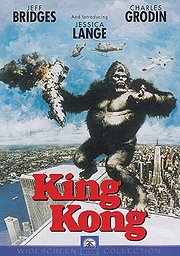

King Kong

U.S.A., 1976

Director: John Guillermin

The Petrox Oil Company sends an expedition by ship into Micronesia, hoping to find petroleum deposits on uncharted Skull Island. Group leader Fred Wilson and scientist Bagley believe that the vapor surrounding the island may come from oil, but Princeton University paleethnologist Jack Prescott — a stowaway — suggests animal respiration, and talks of ancient accounts of Kong, a prehistoric monster. Dwan, a prospective starlet and sole survivor of an explosion that destroyed a film producer’s boat en route to Hong Kong, is picked up before the ship reaches the island. Ashore, Wilson, Bagley, Jack and Dwan come upon an enormous wall and a native ritual in which a girl is about to be sacrificed. That night, as Dwan is about to keep a sexual rendezvous with Jack, she is kidnapped by natives and offered as an altar gift to Kong, a forty-foot ape who arrives and carries her away. While Jack penetrates the jungle with a rescue team, Wilson learns from Bagley that the island’s oil deposits won’t be usable for another 10,000 years, and begins to think of capturing Kong for use in Petrox publicity. Kong kills nearly everyone on the rescue team, but while he is fighting a giant snake, Jack manages to rescue Dwan — with whom the ape has become quite enamored. Kong is subsequently trapped in a pit, drugged into submission and put in the hull of a supertanker. On the way back, Wilson persuades Dwan and Jack to get married and appear with Kong in New York, but Jack subsequently refuses to co-operate on moral grounds. At South Ferry, Kong is enraged by the photographers crowding round Dwan and breaks loose, crushing Wilson and others and wreaking havoc. Jack and Dwan flee across a river and enter an abandoned bar, but Kong finds and retrieves Dwan. Jack has meanwhile observed that the World Trade Center resembles a rock formation on Skull Island and urges citv officials to let Kong proceed there, receiving their promise that he won’t be injured. But the ape is attacked on top of the Center by flamethrowers and army helicopters; trying to protect Dwan, he is seriously wounded and topples to his death. In front of the giant corpse, Dwan plaintively calls out for Jack while a crowd of photographers and spectators keeps the couple apart.

Adapted from one of the greatest of all Hollywood films, the second edition of King Kong moves along reasonably well as a half-jokey, half-serious contemporary ‘reading’ of its predecessor; as an accomplishment in horror and fantasy adventure, it does not measure up to even the small toe of the original. Three years ago (in The Free Paper, February 6, 1974), Elliott Stein commented that young audiences today see the first Kong “as black, beautiful and bound in chains by a white master, or as any simple creature destroyed by cities, machines or the United States Air Force. For some of them, Denham [the filmmaker/ explorer of the original, whose role is taken over in the new version by Wilson] is the Yankee hustler run amok, the bomber of Hanoi”. This is the basis of the revision, although a good deal more contemporary angst is also thrown into the stew. With a hero (well played by Jeff Bridges) clearly patterned after Richard Dreyfuss in Jaws, a villain (quite unlike the sympathetic Denham) representing the collective evils of big business, advertising, Watergate and imperialism (so that the capture of Kong is made to resemble a defoliation manoeuver), and the poor ape himself transmogrified into an unlikely ecology symbol, Dino De Laurentiis’ expensive piece of mischief is visibly designed to obliterate the past with a tidal wave of arch modishness. Its value as an expression of liberal morality can easily be gauged by noting that the film’s most glaringly racist statement is uttered by the hero, an erudite bearded hippy with a credit card who, after remarking Kong’s importance for the natives (“He was the terror and the mystery of their life, their magic”), goes on to say that, without him, they are bound to turn into alcoholics — a notion that appears to add redskins to an already crowded melting pot. The silliest lines, however, are accorded to Jessica Lange, a likeable Tuesday Weldish ingenue whose range is regrettably not broad enough to encompass fear (the speciality of Fay Wray, whose non-stop screams and writhings — brilliantly anticipated in the original’s ‘screen-test’ scene on ship — are usually replaced here by languid expressions). “You goddam chauvinist pig ape !” she remarks to Kong at one point, before inquiring about his birth sign; earlier, after explaining how she inadvertently escaped death by refusing to watch a movie on a ship before it exploded, she asks excitedly, “Did you ever meet someone before whose life was saved by Deep Throat?” Considering how often Kong’s facial expressions are humanized into lascivious grins and leers, one might suppose that the true symbolic counterpart of this remade monkey is indeed the collective male audience of Deep Throat, similarly imprisoned in a conundrum of sexual pathos by the act of looking. (“Come on, Kong, forget about me”, Dwan urges him in the jungle, “this thing is never gonna work”.) Given such an absurd blend of significations, it is scarcely surprising that the new Kong (thirty-six minutes longer than its predecessor) omits four of the five secondary prehistoric beasts on Skull Island — retaining only the giant snake, which looks like a risible piece of cardboard beside its remarkable forerunner. The extraordinary thing about the original’s special effects is that one seldom notices them; even their more ‘dated’ aspects mesh perfectly with the dreamlike textures and rhythms, the awesome hallucinatory sense of size and scale, in a narrative that moves too quickly and relentlessly to give the spectator much time to raise questions about theme, logic or technique. The prosaic new version, more concerned with spectacle than narrative, gives one little opportunity to think about anything else.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM