My column for a Spanish monthly film magazine, submitted in mid-December 2021. — J.R.

What first led me to Radu Jude’s provocative Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn wasn’t the Golden Bear it won in Berlin. Ever since Titanie received the Palme d’Or at Cannes, I’ve figured that any film, no matter how silly, can win the top prize at a major film festival. It was mostly the declaration of J. Hoberman in Artforum, who listed it first in his 2021 Top Ten and called it “the movie with the most relentless focus on the way we live now.”

In certain ways, Jude’s feature recalls Dušan Makavejev’s WR: Mysteries of the Organism half a century ago. A few of the parallels: an awkward two-part title; an Eastern European filmmaker examining the complex relationships between sex and politics, with pessimism about some of the consequences of sexual liberation and the brutal victimizing of a politically lucid heroine; a heady mix of various materials and different forms of discourse, including a bold fusion of fiction and documentary; a lot of footloose shooting on urban streets. But insofar as Hoberman’s claim for the film seems both apt and important, it isn’t really similar to Makavejev’s masterpiece because it comes out of a very different period—during a global pandemic, not during or just after the countercultural 1960s.

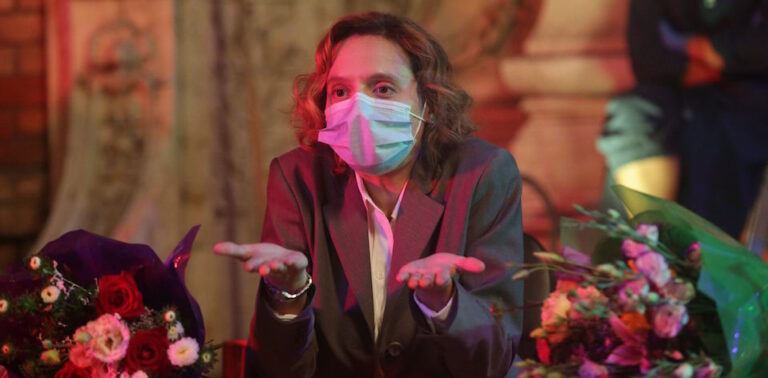

The themes and materials of each film are hardly the same. Makevejev’s emphasis is largely on the theories, activities, and impact of Wilhelm Reich; Jude’s is on the consequences that arise when a raunchy sex tape of a married couple is posted online and goes viral.

As I noted in my last column, I was bored by Jeanne Moreau’s interminable, symbol-laden walk through Milan in Antonioni’s La notte [1961], inspiring one critic [Dwight Macdonald in Esquire] to remark that the Talkies had become the Walkies. In striking contrast, I find Katia Pascariu’s even more protracted walk through Bucharest neither boring nor pretentious, perhaps because it is far more purposeful in narrative terms (she is running several errands) and because Jude’s camera style is far more interrogative and exploratory, repeatedly panning away from Pascariu to her surroundings to discover how they might relate or else fail to relate to her. Antonioni clearly had a Statement in his mind about his heroine and the modern world that he wanted to illustrate, Jude is more open about what he doesn’t already know and needs to search for. He reserves his own didacticism, more politically based and politically coherent than either Antonioni or Makavejev, to another portion of the film, aphoristic and sarcastic, that recalls both Ambrose Bierce’s The Devil’s Dictionary (1906) and Gustave Flaubert’s Le Dictionnaire des idées reçues (1911).