From the Chicago Reader (January 20, 1995). — J.R.

NOBODY’S FOOL

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Robert Benton

With Paul Newman, Jessica Tandy,

Bruce Willis, Melanie Griffith,

Dylan Walsh, Pruitt Taylor Vince,

Gene Saks, Josef Sommer,

and Philip Seymour Hoffman.

Since most Hollywood movies of the 90s offer unabashed fantasies, the hero’s success has become something of a given. Regardless of the odds against him (seldom her), one feels sure that he’ll emerge unscathed — triumphant over his enemies, often rolling in wealth, and with the lady of his choice at his side. Of course people often go to movies in order to bask in a universe of wish fulfillment, and most of our contemporary films are roughly akin to the fantasies of opulence and goodwill offered to Depression audiences 60-odd years ago (though it’s hard to think of many recent parallels, apart from a few TV docudramas, to Warner Brothers’ gritty, socially conscious melodramas of that period).

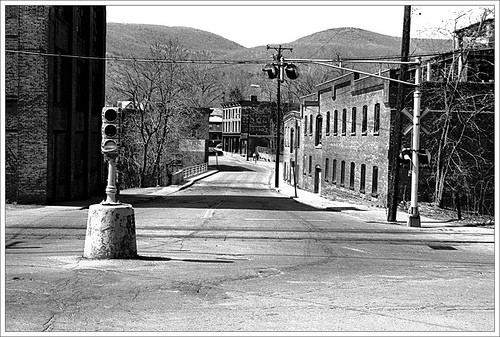

So when a Hollywood movie about failure comes along, it has the unexpected ring of authenticity: for all its sentimental safety nets, Nobody’s Fool looks and feels a good deal like much of U.S. life as it’s currently being lived: virtually everyone qualifies as an ornery fuck-up, complains incessantly about his or her lot, and sees no practical way out of life’s morass of everyday complications. Even more surprising, this beautifully acted slice of grubbiness isn’t viewed as any sort of fall from a former golden age or a temporary hitch in the long march toward utopia; pretty much everything one sees in the ramshackle small town of North Bath — in upstate New York, where the entire movie is set — registers as business as usual, with no end in sight.

Given the track records of writer-director Robert Benton — adapting here a lengthy novel by Richard Russo — and Paul Newman, I can’t say that this is what I was expecting. As clever as Benton’s collaborations with writer David Newman were in the 60s — in Esquire and as the coauthors of the Bonnie and Clyde and There Was a Crooked Man screenplays — his subsequent career has generally seemed both limited and limiting, whether he’s been turning out dehydrated pastiches of his favorite auteurist directors (Bad Company, The Late Show, and Still of the Night) or offering a macho-centric account of a broken marriage in the Oscar winner Kramer vs. Kramer. But I missed Places in the Heart, regarded by some as one of Benton’s best, and found myself warming unexpectedly to parts of Billy Bathgate (which he directed but didn’t write). The most damning thing I can say about most of his other pictures is that I can barely remember them, and don’t feel much like returning to them even now.

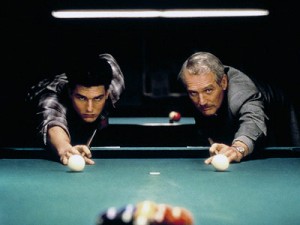

Paul Newman, on the other hand, has long been a favorite of mine, though my admiration took a beating when I saw him grandstanding so shamelessly for his Oscar in The Color of Money, proffering a kind of brassy actorly rhetoric that tended to overcome the movie, and that carried over somewhat into Blaze and The Hudsucker Proxy (though he gave a much quieter, better performance in Mr. & Mrs. Bridge). Having established himself as a liberal icon over 40 years of movie acting, he’s almost guaranteed a free ride in people’s affections, yet he’s rarely a lazy performer. So his hectoring of the audience in The Color of Money — some of which could also be seen in Buffalo Bill and the Indians ten years before — was like a cynical sales pitch, motivated by the feeling that he wasn’t getting enough official accolades. Now that he has them he seems willing to hold back, soliciting his audience’s collaboration instead of demanding its brute submission. And ironically the upshot of that restraint may be another Oscar, this one more deserved.

Not very much happens in Nobody’s Fool; petty events and, for the most part, petty emotions rule life in North Bath. When we hear that a banker in town (Josef Sommer) expects to make a killing in real estate by helping to set up something called the Ultimate Escape Theme Park (“opening 1995” declares a hopeful banner stretched across the sleepy, indifferent main street), we know right away that he’s a fool.

The banker’s mother, Miss Beryl (Jessica Tandy), is a widow who sometimes speaks aloud to her late husband. Once an eighth-grade teacher, she rents her upstairs rooms to a former pupil, Donald Sullivan — a 60-year-old free-lance construction worker (played by Newman, at 70, without a stretch), known as Sully. Alone among the North Bath residents, she doesn’t seem to qualify as a fool or a failure; this is one of Tandy’s last performances, and the film is much too respectful to grant her the sort of plebeian status just about everybody else has. But she seems a good deal more caring and sympathetic toward Sully than she does toward her banker son, an attitude replicated throughout the town, in which makeshift and surrogate families tend to be more reliable and enduring than marriages and blood ties.

Sully works, when he works, for Carl Roebuck (Bruce Willis), the philandering owner of Tip-Top Construction Company, who mainly regards him with derision. A semifunctional near-derelict named Rub Squeers (Pruitt Taylor Vince) sometimes serves as Sully’s assistant and sometimes asks him for handouts. Sully has a running feud with Carl about compensation he claims he’s owed for a knee injury, and one of the film’s first scenes shows Sully trying in vain to win a legal settlement against Carl with the aid of an ineffectual local lawyer, one-legged and Jewish, named Wirf (Gene Saks). As petty revenge against Carl, Sully repeatedly swipes his snowblower, and Carl repeatedly reclaims it. About the only edge Sully can claim over Carl is the flirtatious friendship he maintains with Toby (Melanie Griffith), Carl’s neglected wife, who’s getting fed up with her husband’s affairs with his secretaries. Toby and Sully even playfully fantasize about taking off for Hawaii together, a running theme.

Most of the movie’s limited plot charts what ensues when Sully accidentally crosses paths with his grown son, Peter (Dylan Walsh), who’s returned to town with his wife and two little boys to visit his mother for Thanksgiving. Sully left his wife when Peter was still an infant, so father and son barely know each other; but when Peter splits acrimoniously with his own wife, who takes one of the boys with her, Sully gradually befriends his other grandson and hires Peter to work with him.

Peter recently lost his job as an English professor and so is every bit as desperate for work as Sully and Rub; still, Peter’s working for his father causes some jealousy in Rub, who’s especially riled when Peter calls him Sancho. I take this as a reference to Sancho Panza, Peter’s way of comparing his wayward father to Don Quixote. The uninflected, artful way this reference is dropped in is typical of this picture, which handles exposition so casually that the fictional world created always seems a little broader than any given scene, inviting the audience’s collaboration.

For better and for worse, Nobody’s Fool is a boys’ movie, and a white boys’ movie at that: we see no nonwhite characters, and women are generally viewed as inscrutable or, at best, semicomprehensible. This is of course a commonplace in Hollywood movies, and presumably Russo’s novel has the same slant. (One of the incidental pleasures of Gillian Armstrong’s Little Women as a girls’ movie is that it marginalizes the male characters the same way most American genre films marginalize women. In 1976 the disco-musical Car Wash played a similar trick by using white characters as “colorful” comic relief.) It’s a limiting view, of course — Nobody’s Fool portrays both Sully’s former wife and Peter’s wife so elliptically that they’re like older and younger versions of the same bitchy cartoon. But at least Nobody’s Fool has a view, which is more than can be said for the committee-generated narratives of most other recent Hollywood releases.

In this film Benton has more fully absorbed his auteurist influences: the male camaraderie he evokes in Nobody’s Fool is unmistakably akin to what we find in Howard Hawks movies, yet it never smacks of self-conscious homage. (The only “homage” I spotted here is to Benton’s own Bonnie and Clyde, though I’m told the same verbal reference also figures in the novel.) Benton fully acknowledges his indebtedness to Hawks in an interesting interview he gave Chicago-based filmmaker and video artist Chris Keathley, published in the current Film Comment. Benton even notes that Only Angels Have Wings was his model for Nobody’s Fool — “although this is not about pilots,” he says, “and it’s anything but a tropical country. But it’s about this community of men. And the one woman, the strong woman.”

But who is this strong woman? Is Benton referring to Toby or to Miss Beryl? The fact that we can’t be sure — whereas we are sure in the Hawks movie that the “strong woman” is Jean Arthur, not Rita Hayworth — suggests that Benton tends to regard “the strong woman” as an abstract narrative function, not an actual character. He fails to match the Hawksian model because he doesn’t create a full-blown female character, even on the periphery. (Miss Beryl is like a presiding deity, and sexy Toby an earth mother.)

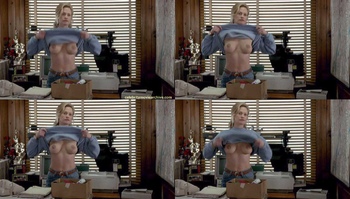

A couple of women I know have objected to the scene in which Toby, responding to Sully’s ragging about Carl’s secretary’s see-through blouse, briefly raises her sweater and flashes her breasts at him (and us). It’s just the sort of thing that happens in boys’ movies, but here the point is more the extended reaction shot of Sully: Newman performs a wonderfully underplayed comic cadenza of charmed befuddlement and momentary embarrassment — like a four-bar break in a jazz number by Lester Young, a laid-back dovetailing of angularities, soft textures inside hard edges. I suppose he could have performed the same cadenza without the tits shot, but the effect would have been rather coy. And the audience would have been less involved in Sully’s grateful yet bemused hemming and hawing — an audience admittedly presumed to be composed mostly of men.

But this is a movie defined by limitations, and it’s to Benton’s credit that he usually seems to recognize that fact. For all the movie’s sensitive use of locations, the world we see is as tightly circumscribed as in a play; when Toby and Sully speak of “Hawaii,” it’s an abstract, offstage Hawaii, rather like “Moscow” in The Three Sisters (though Nobody’s Fool evokes Chekhov’s short stories more than his dramas). All the action takes place between Thanksgiving and the Christmas holidays, and the omnipresent snow and resulting sense of confinement and coziness are as much constants as any of the characters. Similarly, most of what we wind up knowing about Sully’s past is centered around the shabby ruins of the house where he grew up — a haunting, desiccated cadaver of a building and the film’s most inspired setting, occasioning what may well be its most emotionally complex scene.

What holds this movie together besides male camaraderie is a pronounced sense of class camaraderie. In one scene that strikes a rare false note, Sully humiliates the banker in a local diner, to the audible amusement and appreciation of the other customers. But this isn’t the kind of class solidarity one expects to find in a small-town diner, even this one; it’s strictly a Hollywood conceit. If someone like Newman weren’t playing Sully, I doubt Benton would have even tried to get away with it.

Indeed, one reason Nobody’s Fool can confidently explore the poetry of failure without ever ceasing to be a feel-good Hollywood movie is the presence of movie stars: Newman, Willis, Griffith, Tandy. They function as virtual guarantees that no matter how low these characters’ fortunes may sink, it’s all a game of “let’s pretend” anyway. Movie stars help us suspend our disbelief, reconciling contradictions in a way mere mortals can’t: after the merest coaxing from Benton’s fluid script, we believe that the shiftless Newman, the sadistic Willis, the underappreciated Griffith, and the fragile Tandy wind up embodying the opposites of these traits. This doesn’t usually suggest so much a moral development (though there are traces of this in Sully) as a skillful Hollywood con job whereby covert traits become overt and vice versa. If stars are negotiable coin, each one must have a flip side. Similarly, once the relative reality of these characters has been established, the movie can get away with a slew of wish fulfillments, many of them during a surrealistic, hilarious poker game late in the film in which Carl and his latest bimbo gamble away their clothes, Wirf loses his wooden leg, Sully makes a pile, and the local police chief has fallen fast asleep.

What this scene and this movie are saying is that we all need our enemies, that in small towns friends and enemies are often indistinguishable, that sheer cussedness is both lovable and debilitating, that misery loves company and that failure therefore imparts a sense of belonging, even a sense of purpose. The scene in which Sully and Toby briefly muse on what might have been between them is as romantic and escapist as any Depression-era movie; one can almost feel them turning into jewel thief Gaston Monescu (Herbert Marshall) and perfume heiress Mariette Colet (Kay Francis), exchanging regrets in the penultimate scene of Ernst Lubitsch’s Trouble in Paradise: “But it could have been glorious.” “Lovely.” “Divine.” So it makes sense that this movie about terminal nonachievers ends in a kind of euphoria, Sully wearing a shit-eating grin of contentment on his sleeping face.

I suppose it can be called a lie, but set alongside the other Hollywood fantasies of the moment, it’s also a form of truth. The others — responding in ostrich fashion to the inescapable reality that this country is becoming a second-rate world power with a third-rate quality of daily life — exist in a mode of perpetual, willful denial. At least this movie encourages us to treasure what we have, however shopworn. Its promotion of togetherness through mutual recognition reminds me of something film critic Kent Jones wrote a few years back about the changing face of our culture and of movies, as home viewing replaces communal theatrical viewing: “For the last several years the triumph of product over process has been the sole meeting place for Americans from every layer of the socioeconomic strata.” Such technologies as video and laser discs “have changed relationships between art perceiver and art object. A sense of mastery is offered; rather than going out and finding, looking, perceiving the world, one makes a world of one’s own. The artwork is less a meeting ground, more a collector’s item.” What I like about Nobody’s Fool — strictly an old-fashioned virtue, best experienced in movie houses — is that it’s less a collector’s item, more a meeting ground.