This was published at the end of my first year at the Reader, in their Christmas issue. –J.R.

BROADCAST NEWS *** (A must-see)

Directed and written by James L. Brooks

With Holly Hunter, Albert Brooks, William Hurt, Robert Prosky, Lois Chiles, Joan Cusack, and Jack Nicholson.

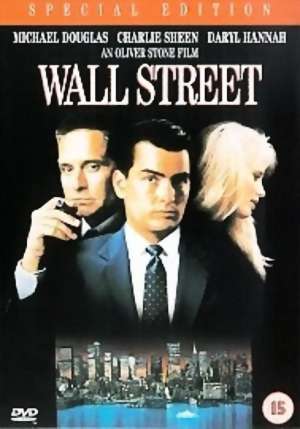

WALL STREET ** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Oliver Stone

Written by Stone and Stanley Weiser

With Charlie Sheen, Michael Douglas, Martin Sheen, Daryl Hannah, Terence Stamp, Hal Holbrook, and Sylvia Miles.

Both Broadcast News and Wall Street score as punchy, energetic movies that are designed to feel as contemporary as possible without taking place in the literal present, and both pivot around a moral reckoning that accompanies economic cutbacks -– as if to remind us that this country’s Reagan-inspired spending spree, which tripled our trillion-dollar national debt, seems to be drawing to a fearful close. Apart from offering behind-the-scenes glimpses of their all-encompassing, hothouse professional turfs, both movies are built around the mise en scene of a moral crisis that splits the major characters apart –- each one charting a mutual seduction that leads to recriminations and the characters isolated in opposing moral camps. Yet the undisputed effectiveness of these films as entertainment seems at least partially predicated on fudging or at least mystifying the moral issues that they are bold enough to raise.

Broadcast News gives us possibly the most amply fleshed-out characters and talented acting of any Hollywood movie this year: news producer Jane Craig (Holly Hunter), news reporter Aaron Altman (Albert Brooks), and news anchor Tom Grunick (William Hurt). Gracefully dovetailed into their personal interactions, and all but indistinguishable from them, is a fascinating look at some of the processes that shape the TV evening news; yet an encyclopedia could be written on all that the film leaves out, skirts over, or strategically obfuscates.

The moral crisis, which occurs just after several members of a Washington, D.C., bureau get sacked, involves the discovery that Tom has manufactured rather than merely “reported on” his own tears in one of his own stories, a feature concerning rape. In contrast to this example of questionable reporting is an earlier sequence of “good” reporting –- the highlight of the film –- when Aaron, Jane, and Tom collectively produce a news story about Libya. Aaron communicates by phone to Jane, who speaks into a concealed earpiece to Tom while he’s on the air. The complex means by which Aaron’s expertise gets translated into Jane’s editorial savvy, which is in turn translated into Tom’s charismatic delivery, is excitingly conveyed, and writer-director James L. Brooks is masterful at making it all immediately legible.

But the movie is so wired into these characters’ experiences of the two news stories that the question of their respective value to an audience is never even brought up, much less considered. More generally, the filmmaker is so fixated on what goes into news reportage that he actively shields us from thinking very much about what comes out of it. To give him credit, his focus is on characters more than ideas, or, rather, on ideas through characters –- as in Terms of Endearment, his only previous film, or The Mary Tyler Moore Show, which he helped to create. Far from being preachy like Oliver Stone, he leaves the moral issue of Tom’s tears (and deception in general) unusually open; in previous scenes, he shows Jane tactfully lying to Aaron (about Tom’s perception of Aaron’s weekend anchoring) and Tom tactfully lying to Jane (about his father’s reaction to one of her angry outbursts), so that an intricate sense of moral relativity is established.

At the same time, Brooks’s absorption in his characters makes his ideas and narrative structures fuzzy around the edges, even if they’re warm and firm at their centers. This may help to explain his dubious decision to preface Broadcast News with a cutesy prologue offering caricatures of all three characters as kids –- objectionable only because it shortchanges their complexity as adults –- and an even more problematic epilogue that shows them seven years after the main action. The latter, apart from creating some nonfunctional ambiguity about when the main action occurs (references to the contras and Arnold Schwarzenegger suggest the present, which improbably places the last scene in 1994!) is feeble conceptually as well as technically. The only significant new information -– that Tom has turned down a position as managing editor at the New York bureau that Jane may accept -– reiterates a point about Tom (his modesty about his own brains) that has already been well established; and there’s a jarringly mismatched close-up of Jane with an illogical lighting change that is a shock in relation to the technical polish of the rest of the film.

At his best, Brooks is so intimately engaged in his characters and their milieu that he gets us involved in their abbreviated sign language to one another. When Aaron arranges a meeting with Jane over the phone, he says, “OK — I’ll meet you at the place of the thing where they met that time.” Their intense siblinglike relationship, the most beautiful thing in the film, seems built on the kind of remembered understandings that precludes any need for specifics, and we come away from this movie with a similar feeling of complicity, vague yet subjectively tuned in to the hyperventilated world that they inhabit.

*****

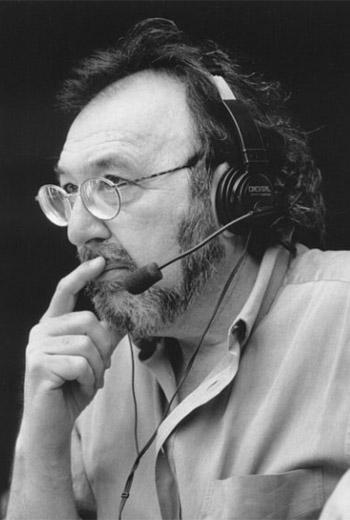

Oliver Stone’s vagueness is at once more sentimental and more cynical, suggesting that the myth of lost innocence that permeates his movies like some omnipresent air freshener ultimately has a lot to answer for. His heroes are usually sadder and wiser at the end of their adventures without having learned anything very concrete, because their education is fundamentally metaphysical; at best, they’ve learned that the world is a more evil place than they originally thought, but how and why this is so seems to matter much less.

The reasons for this are more commercial than philosophical: the trick is to keep us innocent as spectators and, at the same time, make us feel that we’ve somehow gone through a “learning” experience. In Midnight Express, which Stone scripted, this meant being appalled at what an American caught with pot has to go through in a Turkish prison, and indifferent to what a Turk has to go through in the same place. In Salvador, this meant perceiving the political complexities of El Salvador from the vantage point of slob/gonzo journalism and James Woods’s vast collection of Hawaiian shirts -– a sort of enlightened worldview that could be adequately summarized as The Blues Brothers Go to Central America. Even in Platoon, Stone’s best film, the hard bedrock of his combat experience in Vietnam gets needlessly bent out of shape by metaphysical nonsense about a saintly sergeant and an evil one fighting for possession of the hero’s soul, complete with Monarch Notes nudges about which one is supposed to be Captain Ahab.

Wall Street brings back the same hero (Charlie Sheen) and the same Faustian struggle between good father (blue-collar Martin Sheen) and bad father (red-suspender Michael Douglas, a corporate raider), replanted in the bull market of 1985-86. Offering good, trashy fun for most of its running time, the movie also takes us into some of the processes of stockbroking and investment, and confronts an audience with the glib crassness and self-interest of Reaganomics, but only after celebrating them at giddy length. Even the satirical edge is partially blunted by a puritanical response to guilt that makes the denouement -– after the wit and energy associated with evil grind to a halt -– register with all the moral impact of a wet sock.

Michael Douglas makes a suave villain as the unscrupulous Gordon Gekko, Charlie Sheen is wimpy as the innocent stockbroker hero Bud, who gets taken under Gekko’s wing, and Martin Sheen is glumly sincere as Bud’s father Carl, an honest airline worker given a heart attack by one of Gekko’s nefarious deals. Kenneth Lipper has written an appropriately cheesy novelization of Wall Street, with dollar signs used instead of asterisks for section dividers, and it is possible to regard portions of the plot as comic-book Balzac, with Gekko as Vautrin, Bud as Rastignac, and Carl as poor old Pere Goriot. But it is impossible to regard the story seriously in a novelistic sense. This is a movie about male egos rather than characters, and apart from Sylvia Miles’s cameo as a realtor, women function in this world as either poker chips or furniture: Daryl Hannah as a cross between an interior decorator and interior decoration, vanishing from the plot when the going gets tough; an unrecognizably wigged Sean Young as Gekko’s parodically proplike and vapid wife; and Millie Perkins as Carl’s wife and Bud’s mother, her presence so fleeting that she registers mainly as absence.

The moral issues in Wall Street are so clear-cut that nobody needs a scorecard; in Broadcast News, they’re so diffuse that the characters have a much better grasp on them than the audience. Thirty years ago, these moral dilemmas were couched somewhat differently in “serious” contemporary movies like On the Waterfront and A Face in the Crowd, yet the ghosts of those two Budd Schulberg and Elia Kazan collaborations hover over Broadcast News and Wall Street like half-remembered dreams. There’s an eerie matchup between Brooks’s film and the trio in A Face in the Crowd: charismatic, deceitful performer who shoots to the top of the ratings (Andy Griffith); neurotic, ambitious, and idealistic career woman who hankers after the star in spite of her moral qualms (Patricia Neal); and castrated intellectual (Walter Matthau) who sees through the star and hankers after the woman. On the Waterfront had Brando torn between two fathers, a good priest and a bad teamster boss, until he ratted on the latter and took the consequences, just like Bud, after the boss’s ruthlessness finally felled a close family member.

The snap and crackle of insiders’ dialogue that punctuates Brooks’s and Stone’s movies can also be found in Schulberg’s scripts, and the macho solipsism of Wall Street is similarly a Schulberg trait. (From the latter’s 1972 book The Four Seasons of Success: “I have always found writers even more sensitive than women to the milestones of age.”) There are even certain traces of Sammy Glick, the hero of Schulberg’s novel What Makes Sammy Run? , in Brooks’s Tom Grunick and Stone’s Gordon Gekko. What makes these new morality plays different is that their moral positions are partially confused and compromised by what makes them most appealing as movies: the vibrant people in Broadcast News, the glitz and energy in Wall Street.

Published on 25 Dec 1987 in Chicago Reader