From the Chicago Reader (October 4, 1996); also reprinted in my collection Essential Cinema. — J.R.

Blush

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Li Shaohong

Written by Ni Zhen and Li

With Wang Ji, Wang Zhiwen, He Saifei, Zgang Liwei, Wang Rouli, Song Xiuling, Xing Yangchun, Zhou Jianying, and Cao Lei.

The use of multiple perspectives in Chinese painting was not for the purpose of making a hologram, nor was the use of parallel perspectives for the purpose of retaining the true dimensions of the objects represented. What was desired was rather a point of view which transcended that of the individual. The apparent horizon and vanishing point employed by Renaissance perspective made the image seem concrete, but demanded substantial identification with a particular viewer. Such images were perceived as both individual and momentary, seen by a particular person at a particular time. Chinese painting strove for a timeless, communal impression, which could be perceived by anyone, and yet was not a scene viewed by anyone in particular.

Chinese paintings did not portray reality; the world which the viewer entered was the realm of literature or philosophy, a realm which transcended nature. To enjoy a long tableau with small figures, one must shift one’s line of sight left and right, or up and down, a necessary condition for the appreciation of Chinese visual representation. Read more

This originally appeared in the May 23, 1997 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

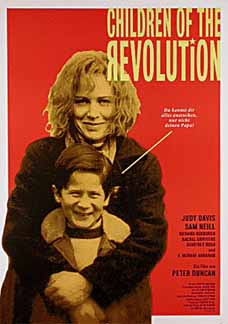

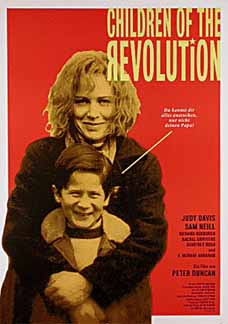

Children of the Revolution

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Peter Duncan

With Judy Davis, Sam Neill, F. Murray Abraham, Richard Roxburgh, Rachel Griffiths, Geoffrey Rush, Russell Kiefel, John Gaden, Ben McIvor, Marshall Napier, Ken Radley, Fiona Press, and Alex Menglet.

This cockeyed story is recounted by several narrators in pseudodocumentary style (a style distantly patterned on Warren Beatty’s in Reds): various old codgers in present-day Australia speak to the camera about the past, their accounts leading into several extended flashbacks. Judy Davis plays Joan Fraser, a red-diaper baby who learned about Karl Marx from her father when he took her fishing. In 1949 — during the darkest days of the cold war — she’s a young woman who still dreams of a workers’ revolution and still idolizes Joseph Stalin. When Prime Minister Robert Gordon Menzies decides that Australia should follow the U.S. into Korea and outlaw communism and sign various anticommunist treaties, Fraser goes ballistic: she gets herself and her boyfriend, Welch (Shine’s Geoffrey Rush), ejected from a movie theater by causing a commotion during a newsreel, decides it would be OK to go to prison (“What do you people want — a discreet revolution?”), Read more

From the Village Voice (October 10, 1974). — J.R.

Discriminations

A book by Dwight Macdonald

Grossman, $10

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Dwight Macdonald’s latest collection of articles is a sequel of sorts to his Politics Past — political-cultural and incidental literary criticism that composes a loose chronicle of the times, taking in a span of nearly five decades.

I blush a little to admit it today, but Dwight Macdonald was the first film critic I ever took seriously. He liked Citizen Kane, Breathless and Shadows and so did I, but I think the clincher was his prose — a rare kind of magazine writing, bursting with energy, that danced or sang or clowned regardless of what it was saying, with a fine ear for polemics and invective. This latter talent has gradually become known as his specialty. More humanistic and less of a school marm than John Simon and a lot more folksy and homespun than Gore Vidal, he shares with them the status of Master of the Chopping Block. (For the best whacks, see my favorite Macdonald collection, Against the American Grain [much of it recently reprinted, in 2011, as Masscult and Midcult: Essays Against the American Grain].) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 13, 1989). — J.R.

THE ACCIDENTAL TOURIST

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Lawrence Kasdan

Written by Frank Galati and Kasdan

With William Hurt, Kathleen Turner, Geena Davis, Amy Wright, David Ogden Stiers, Ed Begley Jr., and Bill Pullman.

Why is the inability to feel such a popular and respected subject in contemporary American movies? William Hurt makes his way through most of The Accidental Tourist, the new Lawrence Kasdan film based on Anne Tyler’s novel, like a human slug, devoid of energy, emotion, or much thought — a freeze-dried mass of nerveless inertia — and audiences appear to be cheering him on, as if there were something intrinsically noble about his condition.

A relatively serious, relatively realistic soap opera, The Accidental Tourist has scant stylistic or formal interest, so how one responds to it depends on how one responds to the story and characters. John Williams’s lush, romantic score asks us and evidently expects us to feel a great deal of tenderness toward its oatmeal hero, and I suspect that many members of the New York Film Critics’ Circle did, for they recently voted this movie the best of the year. But my main response was halfhearted respect (for the script and performances more than for the hit-or-miss direction) tinged with boredom, and a certain curiosity about what all the fuss was about. Read more

A book review published in the Village Voice (January 25, 1983). The version below restores some of the details deleted by an editor. — J.R.

JERRY LEWIS IN PERSON

By Jerry Lewis with Herb Gluck

Atheneum, $14.95

As a longtime Lewis fan who has lived in Paris, I have less curiosity about the French passion for him than most Americans. The unbridled sweep of the all-American ego at its most infantile and traumatized has always been an object of awe and fascination for the French; think of their celebrations of Poe and Faulkner, H.P. Lovecraft and Orson Welles. Call Jerry Lewis “America” (or vice versa) and you have a recognizable psychosexual object that signifies something more than slapstick and telethons. You also have an explanation for why some part of us despises the man — for rubbing our noses into potential traumas we claim to have outgrown, postulating his hysterical comedy as the literal cutting edge of our equilibrium.

One doesn’t ordinarily turn to an as-told-to show-biz memoir for extended self-analysis. But Jerry Lewis In Person exudes an uncomfortable candor that may actually endear Lewis to some of his detractors, while making admirers like me squirm a bit. The childhood sections which predictably dominate depict not only the lonely New Jersey misfit I expected, but also the street-smart chutzpah of a semi-abandoned tough guy who dreamt of murdering his grandfather, killed his cat in a rage when he was five, hated his show-biz parents for not even showing up to his bar mitzveh, and habitually socked anti-Semites and other wise guys (including his high school principal) in the mouth. Read more