A book review published in the Village Voice (January 25, 1983). The version below restores some of the details deleted by an editor. — J.R.

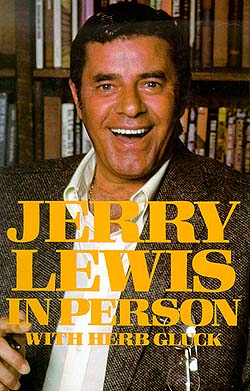

JERRY LEWIS IN PERSON

By Jerry Lewis with Herb Gluck

Atheneum, $14.95

As a longtime Lewis fan who has lived in Paris, I have less curiosity about the French passion for him than most Americans. The unbridled sweep of the all-American ego at its most infantile and traumatized has always been an object of awe and fascination for the French; think of their celebrations of Poe and Faulkner, H.P. Lovecraft and Orson Welles. Call Jerry Lewis “America” (or vice versa) and you have a recognizable psychosexual object that signifies something more than slapstick and telethons. You also have an explanation for why some part of us despises the man — for rubbing our noses into potential traumas we claim to have outgrown, postulating his hysterical comedy as the literal cutting edge of our equilibrium.

One doesn’t ordinarily turn to an as-told-to show-biz memoir for extended self-analysis. But Jerry Lewis In Person exudes an uncomfortable candor that may actually endear Lewis to some of his detractors, while making admirers like me squirm a bit. The childhood sections which predictably dominate depict not only the lonely New Jersey misfit I expected, but also the street-smart chutzpah of a semi-abandoned tough guy who dreamt of murdering his grandfather, killed his cat in a rage when he was five, hated his show-biz parents for not even showing up to his bar mitzveh, and habitually socked anti-Semites and other wise guys (including his high school principal) in the mouth.

No less hyperbolic in the rise to power of Joseph Levitch are the early food transgressions (like getting fired from a grocer’s for biting into a customer’s rolls), sexual frustrations, and sadistic practical jokes he plays on his agent while he’s already touring as a teenager. None of his compulsiveness seems to change after he marries a Catholic six years older (vocalist Patti Palmer) when he’s eighteen, meets Dean Martin soon afterwards, and quickly sails to the top of his profession — or after he splits with Dino a decade later and goes on to become his own director and producer. Eric Bentley argues that the prose of Chaplin’s autobiography can accommodate a Dickensian childhood, but buckles under the celebrity roll-call which follows fame and success. By contrast, Lewis’ exacerbated brashness stays the same throughout: “Many a night I’d get into my XKE Jaguar and speed down Sunset Boulevard, blasting the horn for no particular reason except to feel monumentally important.”

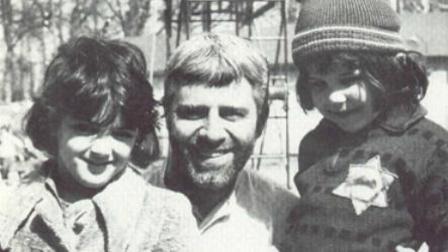

What are we to say about a man who respectfully quotes Edison, FDR, Ayn Rand and himself (“Fame is a big beautiful balloon surrounded by a lot of little boys with sharp pins”), integrates the Sand casino and dining room in the early 1950s, purchases Louis B. Mayer’s 17-bathroom estate, insults Louella Parsons at a surprise party, befriends John F. Kennedy in Chicago circa 1946 (when “we were both young and getting our acts together”), plays golf every single day “for four solid years,” refers to his wife and six sons as if they were afterthoughts, and loses 35 pounds in six weeks in order to play an elderly German clown in a concentration camp who leads Jewish kids into the ovens? (The Day the Clown Cried, still unfinished, promises to be Lewis’s Monsieur Verdoux; his obsession with Nazis throughout the book makes it seem inevitable.)

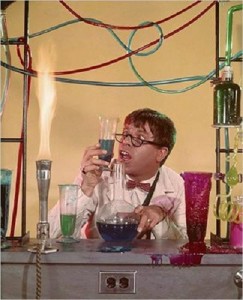

Towards the end, Lewis recounts his fascinating personal encounters with Chaplin and Stan Laurel, and brings us up to date with details about Hardly Working and the forthcoming King of Comedy and Slapstick. There’s an intriguing account of how he arrived at the Jekyll and Hyde parts of The Nutty Professor — the sweet Julius Kelp, whose prototype he met on a train, and the slick Buddy Love (which he denies is Dean Martin, and uneasily acknowledges is closer to himself) — but generally his comments about his films remain pithy and elliptical, seldom repeating material from his 1971 book The Total Film-maker. A megalomaniacal self-portrait of a workaholic, Jerry Lewis in Person is less about art or life than about the driven personality of a man who could tell 85 million viewers (on his 1976 telethon) that “God goofed”, and then stick to his guns even after his fans took offense.

–Jonathan Rosenbaum