From Oui (March 1975). I no longer recall whether or not the editors changed the wording of some of my questions; I suspect that in many cases they did. Because of the length of this interview, I’m posting it in two parts. -– J.R.

Excerpted from the Introduction [obviously not by me]:

“Jonathan Rosenbaum interviewed Morrissey in Paris, shortly after the director had completed his latest films [Flesh for Frankenstein and Blood for Dracula aka Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein and Andy Warhol’s Dracula (sic, sic), only the second of which I’ve ever seen, then or since. -– J.R.] He described being greeted at the door by Nico, of the original and most durable Factory regulars:

“Nico entertained me with comparisons of Paris and Los Angeles, while Morrissey served me orange soda from his refrigerator,” he said. “Morrissey enjoys talking –– the interview was nearly a monologue –- and he speaks in a slightly nasal tone, a cross between Brando and the Bronx.”

OUI: Let’s talk about political content. Your films are usually much more poignant and compassionate than you yourself are reputed to be. In some quarters of the film world, you have a political reputation that might be compared to Ronald Reagan’s. Read more

From Oui (March 1975). I no longer recall whether or not the editors changed the wording of some of my questions; I suspect that in many cases they did. Because of the length of this interview, I’m posting it in two parts. -– J.R.

Excerpted from the Introduction [obviously not by me]:

“Jonathan Rosenbaum interviewed Morrissey in Paris, shortly after the director had completed his latest films [Flesh for Frankenstein and Blood for Dracula aka Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein and Andy Warhol’s Dracula (sic, sic), only the second of which I’ve ever seen, then or since. -– J.R.] He described being greeted at the door by Nico, of the original and most durable Factory regulars:

“Nico entertained me with comparisons of Paris and Los Angeles, while Morrissey served me orange soda from his refrigerator,” he said. “Morrissey enjoys talking –- the interview was nearly a monologue –- and he speaks in a slightly nasal tone, a cross between Brando and the Bronx.”

OUI: There’s a noticeable difference between your early movies, such as Trash, and your latest ones, Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein and Andy Warhol’s Dracula. Is it true, as some critics contend, that you’ve gone from the underground to the surface? Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1977. — J.R.

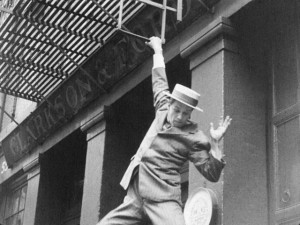

King Kong

U.S.A., 1976

Director: John Guillermin

The Petrox Oil Company sends an expedition by ship into Micronesia, hoping to find petroleum deposits on uncharted Skull Island. Group leader Fred Wilson and scientist Bagley believe that the vapor surrounding the island may come from oil, but Princeton University paleethnologist Jack Prescott — a stowaway — suggests animal respiration, and talks of ancient accounts of Kong, a prehistoric monster. Dwan, a prospective starlet and sole survivor of an explosion that destroyed a film producer’s boat en route to Hong Kong, is picked up before the ship reaches the island. Ashore, Wilson, Bagley, Jack and Dwan come upon an enormous wall and a native ritual in which a girl is about to be sacrificed. That night, as Dwan is about to keep a sexual rendezvous with Jack, she is kidnapped by natives and offered as an altar gift to Kong, a forty-foot ape who arrives and carries her away. While Jack penetrates the jungle with a rescue team, Wilson learns from Bagley that the island’s oil deposits won’t be usable for another 10,000 years, and begins to think of capturing Kong for use in Petrox publicity. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1977. — J.R.

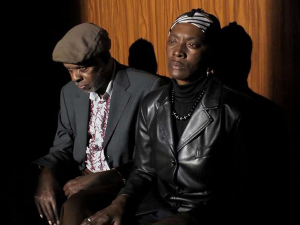

Cooley High

U.S.A.,1975

Director: Michael Schultz

Chicago, 1964. Cochise, Preach, Pooter and another friend, students at Edwin G. Cooley Vocational High School, sneak out of class one Friday and visit the Lincoln Park Zoo; afterwards they play basketball, and Preach, who has been dating Sandra, flirts with the aloof Brenda. At home, Preach finds a letter informing him that he has received a scholarship; that night, he attends a party with his friends and re-encounters Brenda, who warms to him when she discovers his interest in poetry. After the party is broken up by a fight provoked by Damon, Preach and Cochise join Stone and Robert to go joyriding in a stolen car; Preach takes the wheel and drives recklessly, eluding the police after an extended chase. On Saturday, Preach and his friends study briefly for a history exam before going to the movies, fleeing the cinema after Pooter unwittingly provokes a fight. On Sunday, Preach takes Brenda home and they make love; after he casually lets drop that he bet Cochise money that he could sleep with her, she runs away and the next day at school kisses him in front of Sandra. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1977 (Vol. 44, No. 517). This is a movie I clearly went overboard about, even though I still might be inclined to defend it today, and I suspect now that I simply missed the boat by ignoring the screenwriter, Joel Schumacher — who, on the evidence of the subsequent D.C. Cab, surely qualified more as the auteur here than Michael Schultz. — J.R.

U.S.A., 1976

Director: Michael Schultz

Los Angeles. Lonnie arrives to open the gates of the Dee-Luxe Car Wash. Other workers turn up, including fancy dresser T.C. (“Fly”), who has a crush on Mona, a waitress at the restaurant across the street; Scruggs, who has just spent the night with another woman and is afraid to call his wife Charlene; Lindy, a flamboyant homosexual; and Hippo, Justin, Chuko and Goody. After Duane, an angry militant worker, arrives later, the white owner Mr. B drives up with his hippy son Irwin. A hooker escapes from a cab without paying her fare and hides in the ladies’ room. Irwin is ridiculed for hIs Maoist pretensions when he insists on joining the workers, and Calvin, a kid on a skateboard, turns up to pester everyone. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 20, 1995). — J.R.

NOBODY’S FOOL

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Robert Benton

With Paul Newman, Jessica Tandy,

Bruce Willis, Melanie Griffith,

Dylan Walsh, Pruitt Taylor Vince,

Gene Saks, Josef Sommer,

and Philip Seymour Hoffman.

Since most Hollywood movies of the 90s offer unabashed fantasies, the hero’s success has become something of a given. Regardless of the odds against him (seldom her), one feels sure that he’ll emerge unscathed — triumphant over his enemies, often rolling in wealth, and with the lady of his choice at his side. Of course people often go to movies in order to bask in a universe of wish fulfillment, and most of our contemporary films are roughly akin to the fantasies of opulence and goodwill offered to Depression audiences 60-odd years ago (though it’s hard to think of many recent parallels, apart from a few TV docudramas, to Warner Brothers’ gritty, socially conscious melodramas of that period).

So when a Hollywood movie about failure comes along, it has the unexpected ring of authenticity: for all its sentimental safety nets, Nobody’s Fool looks and feels a good deal like much of U.S. life as it’s currently being lived: virtually everyone qualifies as an ornery fuck-up, complains incessantly about his or her lot, and sees no practical way out of life’s morass of everyday complications. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1977. — J.R.

U.S.A., 1968

Director: (not credited)

Dist–TCB. p.c–Drew Associates. For the Bell System. p–Robert Drew, Mike Jackson. assoc. p–Harry Moses. p. co-ordinator–Jean Swain. sc–(not credited). ph–Abbot Mills, Juliana Wang, Ralph Weisinger. asst. ph–Bill Hanson. In color. ed–Naomi Mankbwitz. m.d–Donald Voorhees. songs–fragments of “When the Saints Go Marching fn”, “Hello Dolly”, “Rose”, “The Kinda Love Song” by George Weiss, performed by Louis Armstrong; “Con Alma”, “Swing Low, Sweet Cadillac” performed by Dizzy Gillespie; “I’m in a Dancing Mood” performed by Dave Brubeck; “Light in the Wilderness” by Dave Brubeck; “Forest Flower”, performed by Charles Lloyd. sd–Dave Blumgart, Stan Agol. narrator–Don Morrow. with–Louis Armstrotrg, Dave Brubeck, Paul Desmond, Joe Morello, Eugene Wright, Iola Brubeck, Matthew Brubeck, Michael Brubeck, Catherine Brubeck, Christopher Brubeck, David Brubeck, Darius Brubeck, Charles Lloyd, Keith Jarrett, Dizzy Gillespie, James Moody, George Weiss. 1,921 ft. 53 mins. (16 mm.).

Interviews with Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Dave Brubeck and Charles Lloyd, interspersed with snatches of their music in rehearsal or performance.

An appalling example of how appreciation of jazz can be summarily crushed in the process of supposedly trying to promote the music, this American TV documentary follows the fatal course of rarely letting the music speak for itself for more than a few bars at a time, while encouraging each of the four musicians to pontificate at length about his life and art. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 4, 1996); also reprinted in my collection Essential Cinema. — J.R.

Blush

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Li Shaohong

Written by Ni Zhen and Li

With Wang Ji, Wang Zhiwen, He Saifei, Zgang Liwei, Wang Rouli, Song Xiuling, Xing Yangchun, Zhou Jianying, and Cao Lei.

The use of multiple perspectives in Chinese painting was not for the purpose of making a hologram, nor was the use of parallel perspectives for the purpose of retaining the true dimensions of the objects represented. What was desired was rather a point of view which transcended that of the individual. The apparent horizon and vanishing point employed by Renaissance perspective made the image seem concrete, but demanded substantial identification with a particular viewer. Such images were perceived as both individual and momentary, seen by a particular person at a particular time. Chinese painting strove for a timeless, communal impression, which could be perceived by anyone, and yet was not a scene viewed by anyone in particular.

Chinese paintings did not portray reality; the world which the viewer entered was the realm of literature or philosophy, a realm which transcended nature. To enjoy a long tableau with small figures, one must shift one’s line of sight left and right, or up and down, a necessary condition for the appreciation of Chinese visual representation. Read more

Published by Chicago’s a cappella press in 2000. The jacket reproduced below, which I prefer, belongs to the English edition published by Wallflower Press in 2002; the full title is Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See. — J.R.

To refer to a producer’s oeuvre is, at least to me, as ignorant as to refer to the oeuvre of a stockbroker.

— David Mamet

There are a lot of complaints these days about the declining quality of movie fare, and the worsening taste of the public is typically asked to shoulder a good part of the blame.

Other causes are cited as well. The collapse of the old studio system meant the loss of studio heads who lent their distinctive stamp to each of their pictures — often vulgar and overblown, to be sure, but also personal and engaged — to be replaced largely by cost accountants and corporate executives with little flair, imagination, or passion. The exponential growth of video has made home viewing more popular than theatrical moviegoing and has therefore helped to diminish everyone’s sense of what a movie is, so that the size and definition of the image, a clear sense of its borders, the quality and direction of light, and the notions of film as community event, theatrical experience, or “something special,” have all suffered terrible losses. Read more

This review in the January 31, 1997 issue of the Chicago Reader provoked a fire-storm of angry letters. I was attending the Rotterdam International Film Festival while many of these were arriving, and I can recall having to write a reply to some of them from there. The main point of disputation was whether or not Lucas had in fact appended the subtitle “Episode IV: A New Hope” to Star Wars when it first premiered in 1977; I knew he hadn’t, because I vividly remember attending a first-day showing in Los Angeles (and subsequently writing about it for Sight and Sound in an essay, “The Solitary Pleasures of Star Wars,'” that was reprinted in my 1997 collection Movies as Politics). But quite a few of my indignant readers were convinced that George Lucas in his wisdom had already foreseen that the film would be so successful that it would launch three prequels and were eager to set me straight. The Reader’s facts checkers eventually confirmed my claim by phoning Fox, and I was left musing about the chilling ease with which the Star Wars industry had seemingly managed to rewrite its own history, at least in the minds of many viewers who, having bonded with their parents and/or siblings over the blissful spectacle of mass annihilation at a later date, either weren’t there to see the premiere in 1977 or else were somehow persuaded afterwards to re-imagine what they saw. Read more

From Oui (October 1974). — J.R.

Lancelot du Lac. Robert Bresson has wanted to make this film for 20 years, and now we know that the wait was worth it. The unique vision of the director of A Man Escaped, Balthazar, and Four Nights of a Dreamer has been slow in reaching American audiences, but his treatment of the legend of Sir Lancelot may be the widest door yet into the hermetic beauty of his special world. As usual, Bresson’s actors are all non-professionals: Lancelot is Luc Simon, an abstract painter; Queen Guinevere is Laura Duke Condominas, daughter of sculptress Niki de St. Phalle; Gawain is l9-year-old Humbert Balsan, a former economics student. At the center of the story is Lancelot’s adulterous affair with Guinevere, set in the twilight years of King Arthur’s rule. Around the edges are scenes of violent action — nightmare battles of clanking arrnor in a dark forest, a climactic jousting tournament. Bresson makes us watch the tournament as though it were visible only out of the corner of one eye — an elliptical rush of horses’ feet and lances striking shields. The crowd is heard much more than seen. In his striking medieval tapestry, love in a hayloft and death in the afternoon become interlocking parts of the same spiritual drama. Read more

From Oui (December 1974). – J.R.

Le Trio lnfernal. It’s the Christmas season and Michel Piccoli shoots

a man in the eye — straight through a newspaper he’s reading — while

downstairs, Romy Schneider is finishing off Andrea Ferreol with

similar dispatch. The bodies are stripped clean and plunked into

adjacent bathtubs, which Piccoli promptly fills with sulfuric acid.

Mascha Gomska, Schneider’s sister — who completes the infernal

trio of murderers who slaughter people for their life insurance –

barfs on the living-room carpet, while offscreen, excited by all

these gay and yummy events, Schneider is giving Piccoli an

impromptu blowjob in the bathroom. Later on, after the bodies have

decomposed, Piccoli dons a gas mask, ladles the slop into pails,

then empties the heady stew outdoors while one of the girls is

shown eating spaghetti. Excessive? This Grand Guignol comedy is

nothing but, as it chronicles the exploits of three glamorous

monsters butchering their way to wealth, with lots of kinky sex

on the way. Francis Girod, a producer-turned-director, exhibits an

unusual amount of expertise in his first film. But most of the show

belongs to Piccoli, who dances through all of the Thirties décor

performing a veritable concerto of comic invention. And for

sound-effects freaks, the bathtub glop is recorded so lovingly as it

gurgles into a pit that you can almost taste it. Read more

From the January 2015 issue of Sight and Sound. — J.R.

Horse Money

Director(s): Pedro Costa

Adieu au langage

Director(s): Jean-Luc Godard

Locke

Director(s): Steven Knight

The Owners

Director(s): Adilkhan Yerzhanov

Citizenfour

Director(s): Laura Poitras

TV vote

Borgen

Director(s): several

***

Remarks:

Sadly, I’ve had to omit two exceptional Iranian films (Reza Mirkarimi’s Today, Sepideh Farsi’s Red Rose), two exceptional performances by Juliette Binoche (Fred Schepisi & Gerald Di Pego’s Words and Pictures, Olivier Assayas’s Clouds of Sils Maria), Alain Resnais’ final feature (Life of Riley), and the belated appearance of Orson Welles’ unfinished and ancient but still-sprightly Too Much Johnson. But my top five continue to provoke and expand. Horse Money and The Owners need to travel more, and Locke, which feels like a classic heroic Western, deserves to be recognized as more than just a stunt or tour de force. Adieu au language re-invents 3-D and cinema, and Horse Money, like The Owners, Citizenfour, and Today (not to mention Borgen, in its own fashion). re-invents both the world and its moral prerogatives.

Read more

Read more

I’ve taken this text and these photographs from The Point‘s web site, correcting the grammar of their transcript in a couple of places to clarify my meanings. — J.R.

The following is an edited transcript of remarks delivered by Jonathan Rosenbaum at High Concept Laboratories in Chicago on June 5, 2014. Mr. Rosenbaum and the other two panelists were asked to respond to The Point’s issue 8 editorial on the new humanities.

I’m the odd person out in this gathering because I’m not an academic, although I teach periodically in various, most often relatively unacademic, situations. And plus, I could be described as a failed academic. Before I came to Chicago I was teaching for four years at the University of California, Santa Barbara, but prior to that I actually began my failed academic career in the U.S. where Robert Pippin had his background, at UC San Diego. And in between I was an adjunct at NYU and at the School of Visual Arts, etc.

My academic background, actually, was in English. I was an English major as an undergraduate and in graduate school I did everything but a dissertation in English and American literature. But then I went to Europe and ended up being a journalist.

Read more

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

I’ve been getting increasingly suspicious of ten-best lists–maybe because the studios have been treating them as increasingly important. I’ve always regarded such list making as a critical activity, a form of stocktaking that benefits critics and audiences alike. But it’s becoming obvious that studios value the lists only as a part of their ad campaigns, and they seem to arrange their multiple end-of-the-year screenings and mail out their numerous “screener” videos for the press accordingly. Why else are so many reviewers implausibly claiming that most of the best movies of 2000 came out during the last two weeks of the year or haven’t even surfaced yet? Are they suffering from amnesia? Or are they simply going for the bait?

The studios define the year according to when movies open in New York and Los Angeles, where they’re often first screened in November and December so that they qualify for that year’s Oscars. As a consequence, critics in what the studios see as the hinterlands, including Chicago, are being encouraged to put movies on their ten-best lists that their readers can’t see for some time.

If studios cared about the services performed by criticism–which range from providing background information and an overall context for new releases to launching discussions about their subjects and explaining why these movies matter–they’d try to let critics see films shortly before they have to review them. Read more