From the Chicago Reader (October 6, 1989). — J.R.

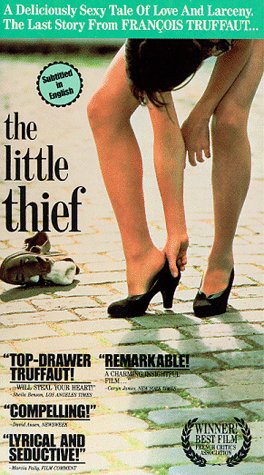

THE LITTLE THIEF ** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Claude Miller

Written by Annie Miller, Claude Miller, and Luc Beraud

With Charlotte Gainsbourg, Didier Bezace, Simon de la Brosse, Raoul Billerey, and Chantal Banlier.

The French cinema has perhaps never been more desperately in the doldrums than now, and this slump is best represented by the trips down memory lane that seem to be a major preoccupation in current French movies. Never entailing research or reevaluation, these simplified, nostalgic foreshortenings of the past often pare away much of what makes that past interesting.

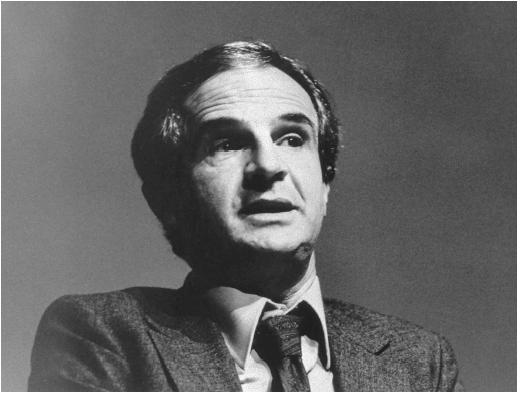

Claude Miller’s The Little Thief (La petite voleuse) is a case in point because it purports to be, at least in this country, the last work of the late Francois Truffaut. (I’m told that no such claims were made about the film when it opened in France, and can understand why; even French amnesia doesn’t ordinarily extend quite as far as our own.) The film was developed out of a long-nurtured Truffaut project that Truffaut considered filming at various points throughout his career; a 30- or 40-page treatment (accounts differ) he wrote with Claude de Givray served as Miller’s starting point, although by all accounts this story has been extensively reworked and embellished, and even given a new ending. Miller worked as production manager on at least eight Truffaut features, so if a posthumous realization of the project was worth carrying out at all, Miller was a logical choice to be in charge of it. The film certainly aims to be Truffaut-like in both style and content, and in superficial ways it succeeds. Unfortunately, the Truffaut it honors is basically the mythical Truffaut — the professional nice guy with a compassionate eye for rebellious youth, puppy love, and little kittens lapping up milk, not the more complex Truffaut who made The 400 Blows, Shoot the Piano Player, Jules and Jim, The Soft Skin, Fahrenheit 451, The Wild Child, or The Green Room.

Just as the popular image of Jean Renoir as the maker of humanist classics like Grand Illusion, A Day in the Country, and The River tends to obscure the darker and more experimental sides of his work, thereby assigning such brilliant works as La nuit du carrefour, Diary of a Chambermaid, and The Woman on the Beach to oblivion, it’s the peaches-and-cream side of Truffaut that has come to stand for the essence of his work — the cutesy light movies like Small Change — rather than the morbid dark side revealed by The Green Room (my favorite of his late works, and uncoincidentally his biggest commercial flop).

The Little Thief, set in 1950, focuses on Janine Castang (Charlotte Gainsbourg), a 16-year-old petty thief and shoplifter living with an aunt and uncle in a small French village in the Deux Sevres region. When she’s caught stealing clothes from a local shop and francs from a church’s collection plate, she’s sent away. She finds a job in another town working as a housemaid for a wealthy couple, and starts having an affair with a 43-year-old married man named Michel Davenne (Didier Bezace). Eventually she switches her affections to Raoul (Simon de la Brosse), a motorbike racer closer to her own age who’s also a thief. The two of them take off with funds stolen from her employers’ party guests.

After a brief idyll on the seashore, Janine is arrested when Raoul is away from their campsite. She is sent to reform school, but eventually escapes with a friend, the school photographer. Janine then announces that she’s pregnant by Raoul, and leaves for her home town to secure an abortion; her friend gives her a camera as a parting gift. She sees Raoul in a newsreel leaving on a ship to fight in Indochina. She leaves her camera as a deposit for the abortion, then changes her mind about the abortion, steals back the camera, and sets out on the road again. A final title tells us that the only thing Janine will steal in the future will be images.

In a recent issue of Sight and Sound, Truffaut critic Don Allen reports that the camera in the plot is Miller’s own addition. Allen also quotes the French version’s closing title, “Medical tests revealed that her baby would probably be extremely restless,” which bears no resemblance to the closing title in the U.S. version. This suggests that Miller initially brightened Truffaut’s ending for French audiences, and then brightened it still further for American audiences, no doubt assuming (correctly) that this was the kind of Truffaut that was wanted over here. (I don’t know whether Raoul’s magical appearance in the newsreel was Truffaut’s idea or Miller’s, but the rather ludicrous execution of it — Raoul actually waves at the camera to make sure that we recognize him — comes across as Truffaut at his worst.)

Miller makes a number of references, both overt and covert, to Truffaut throughout the film. Early on, when Janine sneaks into a bathroom to put on some stolen stockings, there’s a rapid montage of neon signs punctuating her romantic dreams that one can easily imagine being used in an early Truffaut feature. As Allen points out, the surname of Janine’s 43-year-old lover is Davenne, the name of the lead character (played by Truffaut himself) in The Green Room; and when this lover gets Janine to enroll in a secretarial school, there’s a montage sequence crosscutting between a typing course and the couple embracing that recalls a comparable sequence in Truffaut’s episode for Love at Twenty, the feature film composed of sketches by different directors. The overall treatment of Janine as a delinquent contains many references to The 400 Blows, Truffaut’s first feature, and indeed Truffaut originally thought of using Janine’s story in that film in counterpoint to that of the hero Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Leaud).

The mercurial Charlotte Gainsbourg, who plays Janine, accounts for most of the film’s appeal. (She is the daughter of performers Jane Birkin and Serge Gainsbourg, and she shares certain qualities with them: her mother’s charming overbite and her father’s brooding insolence.) The comic moment when she responds to a modest gift from Michel Davenne by kissing him passionately, before they are lovers, is another characteristic moment of echt Truffaut. The very French handling of such matters as Janine putting an end to her virginity and checking into a hotel with a lover nearly three times her age is refreshingly direct and unembarrassed, particularly compared to American treatments of similar subjects.

The guiltless enjoyment of sensuality is a bonus in most French movies, and The Little Thief is no exception. But there’s still something depressingly thin about this picaresque chronicle, and something even more depressing about the readiness of critics and audiences to take it as an adequate representation of Truffaut’s work. The sentimental notion that most people have of Truffaut has already led to a one-dimensional view of who he was and what he did when he was still alive. (An equally distorting mythification process has long been going on with Steven Spielberg, and it’s surely no coincidence that in Close Encounters of the Third Kind Spielberg cast Truffaut as one of his symbolic stand-ins.) People are too eager to overlook, for example, that Truffaut began his career as a film critic who was so intemperate and vitriolic on an ad hominem level that he was the first (and for all I know the last) member of his profession ever to have been banned from the Cannes film festival; he was so caustic that he wasn’t above attacking his colleagues in print for their looks. And people tend to forget that a major part of Truffaut’s polemical stance in his most historically important critical essay, “A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema,” was promilitary and against profanity and atheism, and that he got his first films financed — a ploy also used by his fellow critic Claude Chabrol — by marrying the daughter of a producer.

There were (and are) two Truffauts, not one, and this dichotomy generally extends to his films as well. Like John Ford, he tended to alternate his calculated crowd-pleasers with his more personal and troubling works: after Small Change (1976), he indulged his darker side with painful candor in The Man Who Loved Women (1977) and The Green Room (1978), then went on to make the more crassly commercial Love on the Run (1979) and The Last Metro (1980). Sometimes, like Ford, he even tried to combine the two sides of his personality with equal measure in the same picture — exploring the darkest perversities of l’amour fou in The Story of Adele H. (1975), for example, while using a pretty ingenue (Isabelle Adjani in her first starring role) in the lead, and taking care to cut away from a scene whenever the film’s obsessional aspects started to become really interesting. A much more successful example of this mixture can be found in perhaps his best film, Jules and Jim — an ode to youth, friendship, and freedom that literally ends in a crematorium.

The problem with The Little Thief as a tribute to Truffaut, then, is that it gives us only one half of the dialectic — the half that made money, won prizes, and elicited misty appreciation of his love for the human race — and denies the other half, the one that made him, at his best, a good deal more complicated. Perhaps if The Little Thief goes on to make a bundle, Claude Miller will consider making a feature to celebrate Truffaut’s other half; but I wouldn’t count on it.