There’s an uncommon number of period films

among the end-of-the-year releases and screeners,

a clear indication that we don’t want to spend more

time than we have to in the present moment. Who

could want to? But the problem with most period

films in this country that are insufficiently inflected

with the usual genre reflexes (the beloved ahistorical

escape hatches of noirs, Westerns, and even musicals)

is that most of us know too little about the past

to make it believable enough to feel inhabitable.

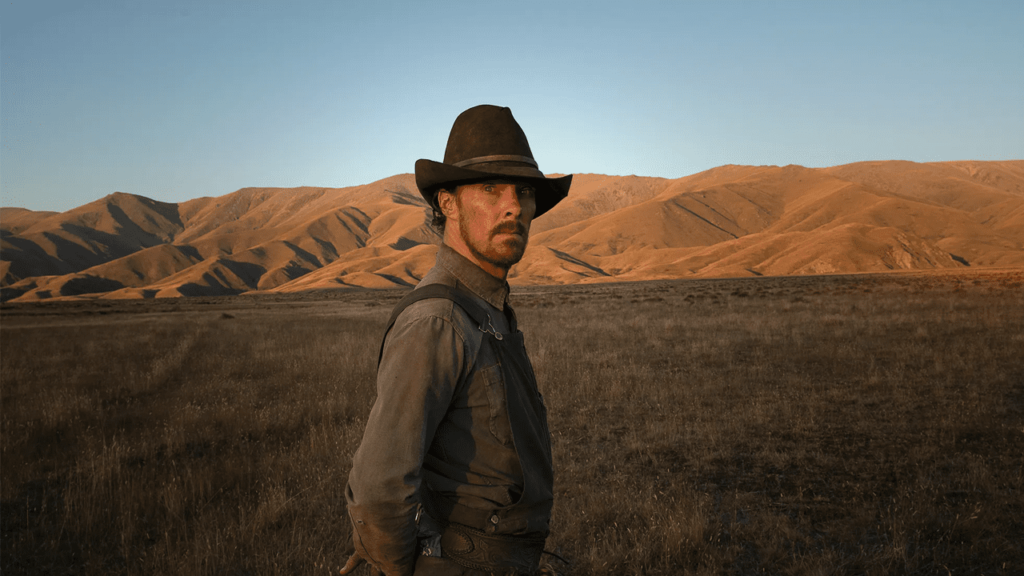

A good case in point is Jane Campion’s sluggish The

Power of the Dog, which tries to critique the Western

genre’s gender stereotypes but winds up stranded in the

present almost by default, in its dialogue as well as its

overall ambience. One simply can’t imagine the

offscreen space of a Montana in the 1920s (e.g., the

nearest town) because the imaginative investments are

too meagre, relating more to the visible landscapes than

to the societies and cultures that the characters

supposedly inhabit.

A far more persuasive view of the U.S. in the 1920s is

found in Rebecca Hall’s densely packed and even

claustrophobic Passing, which is visually and

psychologically far more invested in interiors than in

exteriors, and where the novel being adapted is

contemporaneous with the action being shown. It’s a

complexity that invites us to get lost in its many curves

and hollows, ably assisted by the lead performances.

The James Bond movies have never really been set in

any recognizable present. Their temporal province has

always been a heady mix of colonial nostalgia situated

in a post-colonial future littered with SF gadgets, and

the series’ final chapter, No Time to Die, offers no

exception to their other-worldly out-of-time qualities.

The main achievement here appears to be creating a

politically correct Bond universe without looking

stupid or otherwise abject as the result of doing so.