From Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 492). -– J.R.

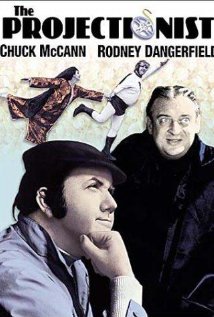

The Projectionist

U.S.A., 1970

Director: Harry Hurwitz

Chuck, a stocky film projectionist who works in midtown Manhattan, hears on a radio about an old man mugged on the Lower East Side, and imagines himself coming to the rescue as Captain Flash. The reverie is broken off by the arrival of his friend Harry, an usher, who hears him describe meeting a pretty girl on the way to work (provoking a romantic-movie pastiche); this is interrupted in turn by Renaldi, the tyrannical theatre manager, who orders Harry out of the booth. Chuck next fantasizes a preview,’The Terrible World of Tomorrow”, before getting off work. As Captain Flash, he loses a fight with the thugs, and the old man informs him that The Bat is after his death ray; they proceed to The Bat’s hideout, where Flash sees the same pretty girl he had described to Harry. In the cinema lobby, Chuck chats with the Czech candy man, who is eventually reprimanded by Renaldi for giving Chuck free lemon drops from the counter. Chuck imagines another preview (“The Wonderful World of Tomorrow”) and a Flash episode in which he visits ‘Rick’s Bar’ in Casablanca and tangles with a prehistoric beast in The Bat’s cave. Passing a movie premiere, he imagines arriving there as a celebrity. Meeting Harry at a pool hall, he resumes his account of spending the afternoon with the girl he met. Leaving the poolroom, he browses in a porn shop and has movie-inspired sexual fantasies, then returns to his flat and watches television until dawn, when he goes out again. As Flash, he is captured in the cave and brought before The Bat (played by Renaldi); the pretty girl saves him by beating up the thugs. Walking to work, he encounters an apocalyptic religious fanatic, sparking off another fantasy, “Man and His Universe”. Back in the projection booth, he tells Harry about a visit to the pretty girl’s flat and a bout of love-making. As Flash, he throws The Bat from a mountain top and celebrates with the girl in musical-comedy style inside the empty cinema.

THE END appears on the screen, and Chuck turns off the projector.

As can be deduced from the above synopsis, the putative plot of The Projectionist offers little more than a series of launching pads for the internal movie fantasies and other inserts, which appear to have received most of the director’s attention; some passable impersonations of movie stars by Chuck McCann and some slightly better comedy by Rodney Dangerfield involving Renaldi’s despotism are just about all that distinguish the rest from sheer padding. The interpolated comic sequences run the gamut from corrosive brilliance (a TV ad for torture instruments comprising “The Judeo-Christian Good-Guy Kit”, delivered with hallucinatory precision by Robert Staats) to the clumsiest kind of would-be slapstick in some of the Captain Flash sections. Most interesting, however, ate the various manipulations and juxtapositions of footage from other films, which interject the hero into the proceedings or otherwise subvert the original meanings in the material –- so that, for example, Ming the Merciless in Flash Gordon, Nazi soldiers from newsreels and galloping Klansmen in The Birth of a Nation all participate in a single malevolent climax; or Captain Flash at another point is seen phoning Humphrey Bogart for advice. The overall impression of such sequences is of a somewhat Jungian view of movie myths as they intersect and blend with one another to compose purely emotional archetypes. In striking contrast, however, to the love of popular cinema evidenced in directors like Resnais and Franju, Hurwitz can presumably only pay homage to his movie memories by subtly degrading them. The world of serials is not viewed seriously, as a child would see them, but rather with retrospective affection laced with a kind of irony bordering on contempt — a sense of shame about indulging in ‘foolishness’ that matches all too readily the masturbatory aspects of the hero’s character and the solipsistic conceits framing the entire film. One factor behind this apparent embarrassment may be the lack of any movie material reflecting a pronounced personal choice on the director’s part, so that the projectionist is made by implication into a stale cross-section composite rather than a singular individual. Hurwitz’s technical ingenuity and comedy are equally based on the assumption that movie myths are essentially interchangeable as well as universal; to see them as impersonally as that is to reduce hero and audience alike to a statistical cipher while virtually leveling all the filmic material to the same mechanistic consistency. Nevertheless, and despite one’s qualms about the philistinism that this approach reflects and elicits, a fair number of laughs and visual effects can be achieved within these cynical limitations, and it is to Hurwitz’s credit that he achieves them.