From the Chicago Reader (February 22, 2002). — J.R.

Monster’s Ball

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Marc Forster

Written by Milo Addica and Will Rokos

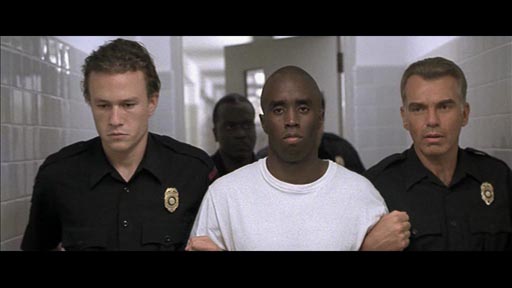

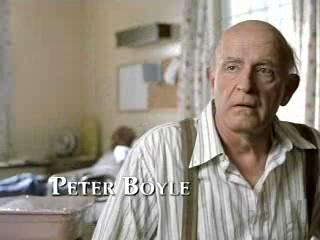

With Billy Bob Thornton, Halle Berry, Peter Boyle, Heath Ledger, Sean Combs, Mos Def, and Coronji Calhoun.

Monster’s Ball is a Hollywood art movie; even the fancy color graphics imposed on the seedy milieu behind the opening credits tell us that. For some viewers, including a few reviewers, the movie becomes bearable only after an hour of misery, when the lead characters, Hank Grotowski (Billy Bob Thornton) and Leticia Musgrove (Halle Berry), finally get around to having their big sex scene (which I have to admit is worth the price of admission). Maybe the sex is prompted by these characters’ mutual misery, but it also happens because this is a Hollywood movie and these are its stars. And because it’s also an art movie, all the misery preceding the scene makes it feel earned.

Hank is a white corrections officer at the state pen in Georgia who recently guided Leticia’s husband, who’s black, to the electric chair, though it takes him a long time — and her even longer — to figure out the connection. Both of them have been pretty distracted lately, having lost their only kids as well as their jobs. Hank’s son, Sonny (Heath Ledger) — also a corrections officer — shot himself after being slapped around and verbally abused by Hank for being a pussy and retching while accompanying Leticia’s husband to the death chamber (later, after discovering that Leticia is the widow of the man he helped fry, Hank too retches, one of many family patterns established in this movie). Sonny’s suicide prompts Hank to quit his job and buy a filling station, despite the disapproval of his father, Buck (Peter Boyle), a racist, embittered former corrections officer. Not long after Sonny is buried, Leticia’s son, Tyrell (Coronji Calhoun) — a butterball addicted to candy bars — is fatally injured by a hit-and-run driver we never see. Hank gets to know Leticia when he gives her and Tyrell a lift to the hospital — not exactly meeting cute, but again, this is a Hollywood movie and these are its stars.

Ultimately this picture is about guilt and absolution, and if it were simply a Hollywood movie without any art trimmings it might try to figure out some way to give us the absolution without any guilt. Someone once remarked that Hollywood gives us an uncrucified Christ, and Monster’s Ball comes pretty close to giving us a comparable sleight of hand, because most of the guilt it portrays turns out to be inherited.

The art movie trappings include misery without much dialogue, characters who are usually much less aware of what’s happening than we are, and frequent allusions to how perceptive we are. I certainly was moved by these trappings, particularly the resourceful acting of Berry and Thornton. (She deserves the Oscar she was nominated for, though I don’t feel the same way about screenwriters Milo Addica and Will Rokos, and I wish Calhoun had been nominated for best supporting actor.) Yet even before this movie was over, I was thinking less about life than about one of the best, if most infuriating, of Pauline Kael’s early essays, “Fantasies of the Art-House Audience.” That’s not because I wasn’t seduced by this movie’s outlandish absolution fantasy; it was because I wanted to understand why I was so easily seduced. What In the Bedroom did for some viewers, Monster’s Ball did for me — it told me exactly what I wanted to hear. That it became convincing despite being almost entirely and ridiculously contrived is a tribute not only to its cast, writers, and director, but also to our desperate need to believe in its thesis. I certainly wouldn’t want to say its appeal is limited to this aspect, but it’s yet another example of an American-movie specialty: it shows us how we can unthinkingly be a party to murder and then be redeemed, be loved, be forgiven. This may be the creepiest version yet of the American Dream — especially at a time when war, hot or cold, makes it so seductive — and it might help explain our weird taste in pop movies lately.

Kael’s 1961 essay suggested “that the educated audience often uses ‘art’ films in much the same self- indulgent way as the mass audience uses the Hollywood ‘product,’ finding wish-fulfillment in the form of cheap and easy congratulation on their sensitivities and their liberalism.” Her main example was Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima, mon amour — at the time a French-Japanese production mixing an interracial love story with reflections about the atomic bomb and France during the occupation could still command mainstream attention — though she also included a couple of Hollywood art movies, The Misfits and 12 Angry Men, in her abbreviated survey. Nowadays domestic art movies get more mainstream attention, and foreign art movies get considerably less, so it’s highly doubtful that a foreign masterpiece could become as fashionable as Hiroshima, mon amour was four decades ago.

I yield to no one as a fan of Resnais’ early pictures, Hiroshima, mon amour included. But I can’t deny that there are debatable reasons for liking any picture, and Kael as amateur sociologist — the best kind, in my book — was adept at unpacking some of the less attractive reasons for liking that movie, such as various kinds of liberal masochism. However, though her essay is still regarded as a classic today, people have unfortunately forgotten Raymond Durgnat’s cogent point-by-point refutation of her essay, which he views as a puritanical rant. In “How Not to Enjoy the Movies,” contained in his 1967 book Films and Feelings. He writes, “Yes, of course educated people enjoy their films in just the same way as the mass audience, as well as in their own way, and so they should, for the latter without the former is just a collection of intellectual formulae. Those who strain to purify themselves into moral computers inevitably conclude by missing all the intellectual points of Hiroshima, mon amour.”

I noticed only a few intellectual points in Monster’s Ball. First, Hank is addicted to eating chocolate ice cream with a plastic spoon, which he commonly orders with black coffee in the cafe where Leticia works, and the way that this craving “rhymes” with Tyrell’s craving for candy bars — or with Leticia’s taste for tiny bottles of Jack Daniel’s — is difficult to miss, especially given that director Marc Forster keeps rubbing our noses in the connections. Second, when Leticia goes to a pawnshop to hock her wedding ring, long after her husband has been electrocuted, Forster puts the pawnbroker’s hands as he appraises the ring directly over a display case of handguns: presumably handguns and all they suggest are as commonplace in this milieu as wedding rings. I suppose one might add to this list that Hank’s rage at Sonny’s show of sensitivity before Leticia’s husband is executed is clearly meant to point to his own failing efforts to stifle such feelings in himself.

I don’t mean to ridicule these points, which are both apt and effective. I’m similarly impressed by many of the jump cuts in the climactic sex scene, which tend to split the complex emotional development of both Hank and Leticia into discrete phases rather than following it step-by-step (though the jump cuts that seem to involve rustling movements inside a cage are simply confusing, whether they’re intended as metaphors or not). But these cuts have to be understood within the wider context established by the film: any social observations become irrelevant because they have no bearing on the actions of the characters, who are motivated entirely by family lineage and personal quirks. Indeed, for all its evidently sincere antiracist sentiments, the movie seems to fall back on the 19th-century assumptions of Emile Zola and Frank Norris when it comes to accounting for why certain people turn out the way they do; good and bad “seeds” and family conditioning seem to explain virtually everything. Hank’s racism and lack of sensitivity clearly derives from Buck, and the sensitivity of Sonny — the sketchiest and least convincing of all the main characters — apparently traces back to his late mother, who also committed suicide.

Here are two pertinent statements attributed to director Marc Forster in the press book: “I approached the material — which was heavy on incidents but not on dialogue — by focusing on how characters reacted to what was going on around them. This means that I encouraged the actors to present their characters in all their desperate humanity, which I hoped would make labels like ‘sympathetic’ or ‘unsympathetic’ seem entirely beside the point.” Six pages later he says, “I always saw Buck as someone who had been living in a cave. That’s the only world he knows. It’s a horrible moment, like in a horror movie, when you realize that a character you think you know is truly evil and much worse than you might have thought.” So his bottom-line assessment of people’s “true” nature wins the day. This simplistic view calls to mind the attitudes of George W. Bush, who was famous as governor of Texas for refusing to alter the sentences of death-row prisoners.

Of course Buck has been living inside a cave — a cave that this movie has constructed piece by piece. It’s a cave that pointedly excludes as many traces of society as possible, ascribing racism strictly to individuals and their own twisted orneriness — the same orneriness, we’re expected to conclude, that led Hank’s mother and later Sonny to commit suicide — and assigning responsibility for capital punishment and even the desire for it mainly to the people being executed. We’re never told what Leticia’s husband’s crime was, but no matter. He accepts the judgment that he’s worthless and deserves to be exterminated, silencing any of our objections before we can raise them. And though this movie shows us in graphic, horrifying detail the process of electrocuting a prisoner — which is entirely to its credit — we’re discouraged from speculating even a little about what led to the sentence.

The absence of society in Monster’s Ball isn’t just an abstract principle but a concrete fact in these people’s lives. (Salon‘s Stephanie Zacharek has rightly noted how “severely underpopulated” the “numerous restaurant and prison scenes in the picture” are, “even for rural Georgia”; no wonder we don’t see the hit-and-run driver who mows down Tyrell.) Of course it might seem churlish to blame Forster or the screenwriters for this, given the presumed absence of society and community apparent when people walk down busy city streets chattering into their mobile phones. But it isn’t being churlish when Monster’s Ball is being applauded for its social sensitivity even though it reinforces most of the currently fashionable asocial attitudes.

The movie becomes an insidious cop-out when it offers the promise of this interracial couple happily running a filling station in the Georgia sticks, all racism held in check simply because Hank’s father is ensconced in a nursing home. We’re even supposed to believe that once his racist father is out of the picture, Hank’s racism and his thoughtless lack of concern for black people in general — epitomized by his refusing to honor the condemned man’s request to tell his wife and son that he tried to call them again but couldn’t, and by his callous treatment of two kids on his property — can effortlessly disappear. At the end he can say “I think we’re gonna be all right” to Leticia, because without society to contend with, racism turns out to be as transient as the common cold — the reverse of the pessimism underlying Samuel Fuller’s White Dog. So the hyperbolic misery that opens Monster’s Ball — an awkward title alluding to a condemned prisoner’s last night — proves to be mainly a false alarm, the storm preceding a rainbow. All’s right in the world, because whatever troubles might be found in individual lives, society can’t threaten us, and individual love can set everything right again.