From Sight and Sound (Spring 1975); I’ve mainly followed the editorial changes (mostly trims) used in the version that appears in my collection Essential Cinema….My apologies for the format problems with this piece, only some of which I’ve managed to resolve satisfactorily. — J.R.

[. . .] Unless it is claimed that a pianist’s hands move haphazardly up and down the keyboard — and no one would be willing to claim this seriously — it must be admitted that there exists a guiding thought, conscious or subconscious, behind the succession of organized sound patterns . . . Of course, it does happen, and not too infrequently, that an instrumentalist’s fingers ‘recite’ a lesson they have learned; but in such cases there is no reason to talk about creation.

— André Hodeir, Jazz: Its Evolution and Essence

I can never think and play at the same time. It’s emotionally impossible.

— Lennie Tristano, circa 1962

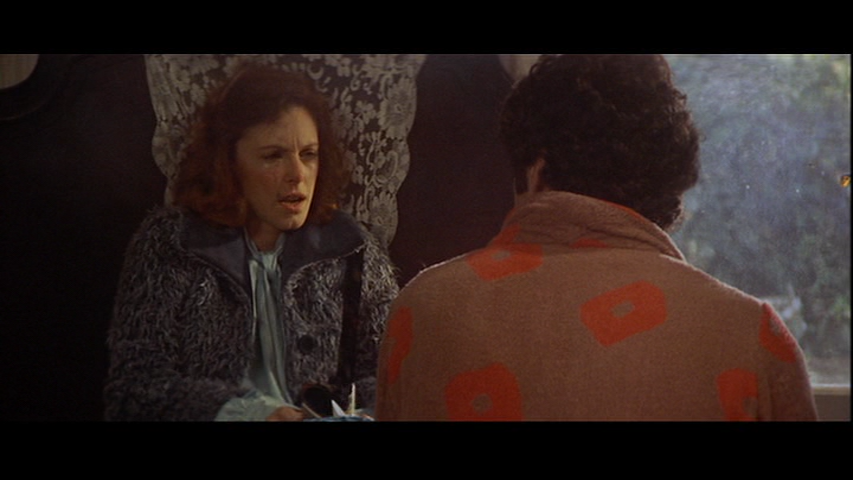

CHARLIE (Elliott Gould): This is the truth. You’re an animal lover, right?/ SUSAN (Gwen Welles): Yeah./CHARLIE: Okay, well: the great blue whale, right? You know about a great blue whale?/ SUSAN (semi-audible): . . . got that wrestling guy, hunh? /CHARLIE: No, it’s a big fish, a big fish, there’s only two or three left in the world. And the truth — the tongue: of the great blue whale: weighs more: than a full, grown, African elephant…/SUSAN: No, that’s not true./CHARLIE: You don’t believe it /SUSAN: You’re just making it up to make me feel better — /CHARLIE: Aw –/ SUSAN: –’cause you don’t like to see me cry./CHARLIE: You feel a little better?/SUSAN (sniffing): Yeah, I do.

— California Split

The first quote comes from a theorist, the second from a jazz pianist; together they only begin to describe the difficulties and ambiguities attending any effort to describe the aesthetic conditions of improvisation — for audience, improviser and theorist alike. Taking the third quote as a test case, it is hard to know where to begin. Is the dialogue written or improvised? Is the scene — Susan, a prostitute, arrives home in tears after falling for yet another of her clients; Charlie, her flat mate, goes to her room to cheer her up — an integral part of Joseph Walsh’s script, or something that Robert Altman and/or Gould and Welles partially or completely concocted on the set?

A skeptic could remark with some justice that it makes no difference: whatever the sources, combinations or relative degrees of calculation and spontaneity, the results on the screen are all that count. But the fact that these results give an unmistakable impression of improvisation — as evidenced by such factors as Gould’s loose, evolving syntax and Welles’ semi-audible, equally vague reference to ‘that wrestling guy’ – is a matter of some importance; without it, our responses to the scene would simply not be the same. If Gould’s rap and delivery were more polished, our attention would be focused on his whole statement as a single gesture: Charlie spouts nonsense to make Susan feel better. But in the scene as played, what we observe is the emphatic (if somewhat ham-fisted) exposition of Charlie’s nonsense and Susan’s reactions, motored on suspense and an element of risk.

One hesitates to make too much of a scene that is small and, for Altman, unexceptional; but the distinction is crucial. Well-composed, cleanly delivered dialogue would perhaps convey an implied moral judgment: Charlie cheers up Susan, therefore he’s ‘good’. Throwing this emphasis slightly off-center, Altman invites us to judge Charlie/Gould, aesthetically as well as morally, on a moment-to-moment basis. Like a matador coordinating his gestures to the unpredictable but inescapable movements of a bull, or a jazz improviser accommodating himself to fellow musicians and chord changes, Charlie/Gould is wriggling his way into the imponderables of a given emotional situation, and to respond directly to his behavior we have to wriggle accordingly; so, for that matter, does Susan/Wel1es.

The difference between conventional methods and Altman’s is one between directness and indirectness, actions and interactions — the actors’, the characters’, the director’s, the scriptwriter’s and our own. It is decidedly a group endeavor, and as such, one that lives and breathes in an intangible no-man’s-land between ‘thinking’ and ‘playing’ for the film-makers, ‘thinking’ and spontaneous ‘reacting’ for the audience: the relative strengths of both values are held in perpetual suspension, with new stimuli that can potentially shift the balance coming along at every juncture. From this point of view, anything can affect everything, and no two spectators are responding to precisely the same film –- the complete ‘text’ is common to all, but each reading of it varies according to attentiveness, temperament and perceptual capacity: an individual selection of what is interesting or relevant and what is not.

This is not an approach that Altman can be said to have pursued with any rigorous consistency, although it seems to figure at one level or another in all his films since Brewster McCloud. Minor details notwithstanding, it cannot be found to any appreciable degree in the box-office hit that made Altman’s name commercially negotiable and the subsequent works financially possible.

MASH is Mr. Roberts revised and updated, but not substantially improved. In striking contrast to the movies that follow, it leaves essentially nothing to chance, programming its effects with the ruthless efficiency that one would expect from a skilled TV veteran. Oriental gongs are intermittently rung on the soundtrack to tell the spectator when to laugh; black-comedy interludes of blood-spurting surgery are periodically introduced to maintain a ‘serious’ war-is-hell backdrop; and for all the apparent verisimilitude of the celebrated overlapping dialogue– controlled by an adept handling of timing and dynamics, where lack of inflection becomes a form of emphasis-no one in the bleachers is permitted to miss a single significant line. Too single-minded to include any serious risks in its strategies, it is unswervingly a thesis film which militates for the heady (if headless) consensus of a mob’s euphoria as part of its overall message: that fun-loving, honest, proficient surgeons are much healthier and a lot easier to take than bureaucratic, militaristic hypocrites and religious fanatics.

For roughly its first twenty minutes, MASH amply demonstrates this ‘audacious’ postulate; after that, it can only repeat its position ad infinitum over a series of tacked-on skits. When Hawkeye (Donald Sutherland) and Trapper John (Elliott Gould) leave for Japan, the structure is already buckling; by the time we reach the football match, the film has clearly been stretched to run on like a TV series (as, indeed it subsequently has), with the Korean War at this point safely out of sight and out of mind. The sensible way of dealing with death and madness, we are good-naturedly instructed, is to forget about them, while the only way to deal with solitude is to ‘join the crowd’ like Sally Kellerman’s ‘Major Hot Lips’ (after being subjected to a proper number of qualifying sexual humiliations), or else go mad like Major Burns (Robert Duvall) — who is sent packing early on, in a straitjacket, to make way for further horseplay.

After this sort of high-powered speciousness, Brewster McCloud (1970) registers as an honorable failure: a species of crazed doodling with all the awkward, endearing earmarks of a promising ‘first’ film, in which a director tries to do and say everything at once, trusting to find his coherence in the cutting room. Wildly overlapping allegory, satire, TV burlesque, social protest, demented bird lectures and conventionally dull songs by John Phillips, the film nurtures a dream of ‘escape by flight’ from convention that is as innocently vague as its hero’s, and as predictably doomed. But along the way are some glancing pleasures that suggest some of the achievements to come: the intercut and overlapping use of René Auberjonois’ bird lecture in relation to the already fragmented plot, at least until this relationship becomes overly rigid and predictable; the debut of Shelley Duvall, an Altman discovery, as a Texas-grown variant of Breathless‘ Patricia; the bold delivery of certain oddball gags — like the instant splattering of a newspaper headline (‘AGNEW: SOCIETY SHOULD DISCARD SOME U.S. PEOPLE’) by a bird dropping, or the appearance of a tough hard-leather delinquent sporting a Porky Pig T-shirt — along with some looser forms of humor, such as John Schuck’s likeable enactment of a conscientious, semi-retarded Houston cop.

It is only after the exorcism of Brewster, in McCabe and Mrs. Miller, that Altman arrives at a fluent and developed style which can support his semi-improvised approach. Henceforth, even his ‘mistakes’, like Images — an old Altman project predating MASH that was filmed after McCabe — will carry a technical proficiency and assurance that can support many calculated risks.

***

Writing, when properly managed (as you may be sure I think mine is) is but a different name tor conversation: as no one, who knows what he is about in good company, would venture to talk all; so no author, who understands the just boundaries of decorum and good breeding, would presume to think all: The truest respect which you can pay to the reader’s understanding, is to halve this matter amicably, and leave him something to imagine, in his turn, as well as yourself.

––– Tristram Shandy, Vol. 2, Chapter 11

According to me it’s a collaborative art. I set a boundary line and framework, but I don’t try to fill it all in. If I tried to put in the middle of it everything that was in my imagination, it would be simply that. It would be a very sterile work. So I try to fill it with things I’ve never seen before, things that come from other people.

— Altman in a recent interview

The ‘open spaces’ that Altman offers to his fellow craftsmen or creates for himself are obviously not identical to the ones that his films offer to audiences, but they are related none the less: the openness and variability of a film’s conception can help to encourage an open and variable response. Broadly speaking, shooting, editing and sound-mixing appear to be regarded by Altman as a process of elucidation, elaboration and discovery as much as one of execution. (‘The script will indicate character and situation,’ he has remarked, ‘what I do comes on top of that.’) Actors are occasionally employed without written parts, invited to ‘fall in with the material“ and create their own roles, or encouraged to alter or expand their scripted parts during rehearsals. Rather than scout every location in advance, Altman sometimes chooses to encounter them only when he arrives with his camera crew.

Equally significant are the ‘open spaces’ that Altman allows for during shooting and then fills at the editing or sound-mixing stage. The various announcements over the public address system in MASH, René Auberjonois’ bird lecture in Brewster and Leonard Cohen’s songs in McCabe were all arrived at and introduced long after shooting began; and one might deduce that the use of Susannah York’s children’s book (In Search of Unicorns) in Images, the title tune in The Long Goodbye, the radio shows in Thieves Like Us and Phyllis Shotwell’s songs in California Split were all partially determined after shooting was over. (Only partially, one assumes, because all four of these ‘independent’ elements figure briefly within the actions of their respective films.)

Most often, these interventions pass from the role of a foreground commentary (mainly explicit in Brewster and Thieves; more frequently loose, approximate and dreamy in McCabe, Images, The Long Goodbye and California Split) to that of a background murmur whenever the scene’s dialogue begins, generally regaining volume over subsequent lulls in the on-screen talk. Bridging scenes or taking up narrative slack while subtly shifting or dispersing an audience’s focus, this procedure distances us somewhat from the visuals and discourages sustained identification with the characters — the reverse of the way music is used in MASH.

But the same technique creates an impression of overloading in much of Thieves Like Us, where the use of Depression radio shows as historical artifacts and ironic commentaries on the characters tends to duplicate points that are already being established by other means (such as the three bank robbers’ mythical sense of their own exploits). Sometimes these editorial nudges are even extended beyond simple redundancy: in the central love scene between Bowie (Keith Carradine) and Keechie (Shelley Duvall), which the actors are clearly capable of sustaining by themselves, the unnaturalistic use of the same radio phrase three times — ‘Thus did Romeo and Juliet consummate their first interview by falling madly in love with each other’ — which is apparently intended to punctuate the successive bouts of lovemaking and convey a mood of time suspended, merely comes across as a self-conscious tic.

In California Split, on the other hand, the supplementary sound material has art inventive, dynamic function in relation to the action, serving more as a lively contrapuntal counterline than as a static one-to-one gloss. In the second scene at the local poker parlor, one of Shotwell’s songs begins loudly over a long shot of the card players’ becomes faint and is overtaken by these players’ dialogue in medium shot, and then resumes loudness over a close-up of Bill — delineating a dodgy kind of fan-dance in relation to a spectator’s diverse routes into the scene. And when Charlie and Bill arrive in Reno, Shotwell’s jazzy recitative-with-piano and Charlie’s independent free-form rap suddenly (and gratuitously) converge on the phrase ‘nobody there’ –- a striking demonstration of the blind vicissitudes of chance (such as the curious proliferation of elephants end Barbaras), which operate throughout the film on multiple levels. [2012 postscript: Lamentably, due to rights issues involving the songs, this moment has been deleted from the version of California Split released on DVD.]

In all Altman’s best films, the emotional center gravitates around a pronounced feeling of Absence — a sense of opportunities lost, connections missed, kindred spirits divided and scattered — and in many respects, the independent sound material serves to embody some form of this failed utopia: a ‘commentary’ of lyrical idealism abstractly bridging discontinuous characters.

***

The contrast with MASH is again striking; there, the solitary characters are the villains, and even Trapper John is made to appear suspicious and unwholesome until he pulls out his jar of olives and joins the snob elite. In Brewster, McCabe and The Long Goodbye, membership in a group is generally depicted as a sign of naiveté. The fantasies spun by minor characters about Brewster and McCabe — like the remarks of Philip Marlowe’s candle-dipping neighbors and Marty Augustine’s entourage of faithful hoods — usually come across as the utterances of gullible, fanciful children; in Images, the ‘healthy’, ‘public’ response of Hugh (René Auberjonois) to the solitary madness of Cathryn (Susannah York) is shown to be comparably myopic.

In Thieves Like Us and California Split, these relationships are less fixed and more complex: Bowie, Keechie, Chicamaw and T-Dub in the former and Charlie and Bill in the latter oscillate restlessly between different kinds of solitude and communal living, and strained or frustrated domesticity — broken homes and temporary arrangements — is a keynote in both films. But even here, the minor characters share a visible kinship with the assorted array of cranks who populate McCabe and The Long Goodbye, each riding on an autonomous wavelength that runs at an oblique angle to everyone else’s. Consider, for instance, Harvey in California Split, an old friend whom Bill looks up in a paint store:

HARVEY: Wait a minute! Don’t tell anybody you came, I’m getting a flash. You see, I have a good amount of ESP. I’m blessed with it — my wife kids me about it — but you should catch it when I get these flashes. Let me see how close I can get to what’s goin’ on here. I get — I get that you’re probably back with your old lady . . . an-n-n that you probably want to paint your garage door — perhaps even the whole front of your house — I’m gettin’ the colour . . it’s a greenish color. Right, how close did I get ?/BILL: I need a loan, Harvey./HARVEY: A loan?/BILL: Yeah.

And that’s all we ever see of Harvey. Like some of the Flemish peasants in Brueghel’s landscapes and certain topics and individual chapters in Tristram Shandy, he emerges briefly in apparent non-relation to his immediate surroundings, but retrospectively blends into an overall pattern of awkward everyday cussedness that comprises an appropriate setting for absurdist-humanist drama. A distant cousin of the eccentrics in Preston Sturges’ gallery of grandiloquent bit players, he is spiritually closer to Dee Mobley (Tom Skerritt) in Thieves Like Us, dislocating the screen door on his shack while counting the money in his hand and not quite aware of it, or Ken Samson’s gate attendant in The Long Goodbye impersonating Walter Brennan to a bewildered gangster.

The pathos of these characters – and countless other examples could be picked from Altman’s menagerie — is directly related to the way that they momentarily take the plot away from the films’ equally displaced heroes; their fumblings are only condensed versions of the clumsy, uncertain relationships of McCabe, Marlowe, the bank robbers of Thieves and the gamblers of California Split to their respective worlds. John McCabe (Warren Beatty) cracks a raw egg into a double-whisky and gulps it down to impress Constance Miller (Julie Christie), but all she cares to take note of is his ‘cheap jockey-club cologne’; more worldly-wise but similarly lost, she inhabits an opium pipe-dream that is equally inaccessible and unknown to McCabe. Legends and ‘professionals’ to the residents of First Presbyterian Church, they are helpless amateurs when faced with the potential challenges of each another, and in many respect the film they inhabit registers as a wistful ode to that lost potential.

Within this context, the banality of Leonard Cohen’s semi-abstract songs becomes workable through its teasing relationships and non-relationships with the action, postulating mythical archetypes that might alternately ‘fit’ or collide with the characters on the screen. Because these relationships are so fluctuating and ambiguous (e.g., is Constance a ‘travelling lady’?), we are forced to construct our own myths and anti-myths out of them, situating ourselves somewhere — Altman doesn’t specify a precise position — in relation to Cohen’s discourse, the story’s and the characters’.

What might legitimately be regarded as a style whose accents and cadences — expressed through zooms, pans and qualities of light and focus, along with shifting stresses on the soundtrack — convey a dreamy vagueness, is equally a broad invitation to find one’s way in it, to merge with a narrative rather than simply be carried along by it. Thus we are free to notice or not notice Constance’s heart-shaped. money-box (and draw or not draw ‘significant’ conclusions); and when we hear intermittent strains of ‘Beautiful Dreamer’, they are not accompanying her opium sessions but figuring in less obvious places: screeched out on a fiddle in Sheehan’s Saloon while McCabe watches her bolt down a tableful of food, and sung by her newly arrived prostitutes as they splash about in the misty bathhouse.

MCCABE (muttering to himself): . . . I tell ya, sometime — sometimes when I take a look at ya I jus, I jus keep lookin’ and-a lookin’ . . . Long to feel yuh little body up against me so bad I think I’m gonna bust . . .I keep tryin’ to tell ya, in a lotta different ways — just one time you could be sweet without no money around . . . I think I could — well I tell ya somethin’, I got poetry in me. I do. I got poetry in me! . . .but — I ain’t gonna put it down on paper, I ain’t no educated man, I got sense enough not to try. . . .

— McCabe and Mrs. Miller

MARTY AUGUSTINE (Mark Rydell) (to Marlowe): You remember the night that Jo Ann became ill and we hadda take her to the hospital. Well, as you can see, she’s had extensive treatment — the finest surgeons, had nurses around the clock, best attention — because, as you know, she’s very near and dear to me. And the prognosis is excellent. Excellent. She’s gonna be fine. Now I left the hospital that night, and I was — I was really upset I was — what was I ?/JO ANN (Jo Ann Brody): Haunted./MARTY: What, what?/JO ANN (louder, more distinctly): Haunted./MARTY: That’s it. Haunted! I was haunted — absolutely haunted by the idea that somehow I’d been unfair to her.

–— The Long Goodbye

As can be partially discerned from the above, inarticulateness and clarity can often register as moral positions in Altman’s films– at least until California Split, where the whole question of a moral context becomes largely suspended. In the absurdist terrain traversed by McCabe and Marlowe, a hired gun (Hugh Millais) describing how to make profits out of dead Chinamen can be a lot more articulate than the leading citizen of First Presbyterian Church, talking to himself; and a psychotic gangster (Augustine) can enunciate sentences a lot more distinctly and lucidly than Roger Wade (Sterling Hayden), a published novelist — even if the former is describing his guilt feelings after gratuitously smashing a Coke bottle across his girlfriend’s face, and the latter is merely trying to communicate affection to his wife through a series of helpless stammers.

Altman’s apparent preference here for his tongue-tied characters over their smooth-talking counterparts (the pompous lawyer in McCabe, the sinister Dr. Verringer in Goodbye) seems to rest on the notion that emotions speak louder than words. And the most serious reproaches that have been leveled against the director — whether for ‘laziness’, lack of intellectual rigor or incoherent rambling — can mainly be traced back to this bias. But on Altman’s behalf, it is worth noting that rigor and clean articulation is not really what he is after: the vagaries of behavior, the indulging of certain moods and the staging of chance encounters, can be enormously expressive even without the dividends of what critics like to call ‘an organic whole’. It is rather like censuring a jazz musician because his improvisations lack the polished form and execution of a classical musician performing a written piece. While it is certainly true that the former is less likely to achieve a finished form, there is a different kind of excitement in the way that he tries to achieve it — a way of regarding ‘form’ as a verb rather than a noun, a process father than a postulate. And the base lines established by Altman for isolating and relating different kinds and degrees of coherence are anything but loose.

In Michael Tarantino’s article “Movement as Metaphor” [which originally appeared in the same issue of Sight and Sound], a persuasive case is made through concrete evidence that the nearly constant movement of the camera in The Long Goodbye affects both our relationship to the film and Marlowe’s relationship to the world around him. In what I hope might serve as complementary evidence of that film’s formal interest (which surpasses, I believe, that of Altman’s other works to date), I would like to show how roughly comparable parameters are at work on the soundtrack, above and beyond the overlapping dialogue — particularly in the extraordinary use of the title tune, a facet of the film that many commentators have taken to be nothing more than a trivial joke.

‘The Long Goodbye’ is a 32-bar standard by John T. Williams and Johnny Mercer that is performed throughout the film in countless versions, none of which is ever heard in its entirety; out of the dozen or so times that parts of it are sung on the soundtrack — mainly by Marlowe, Marty Augustine and Jack Riley (a pianist in a bar) on-screen or by Jack Sheldon and Clydie King off-screen — most of the lyrics can be pieced together, and some of them are worth quoting:

There’s a long goodbye, and it happens every day —

Where some passerby invites your eye

To come her way —

Even as she smiles a quick hello, you’ve let her go,

You’ve let the moment fly —

Too late, you turn your head . . .

[. . .] There’s a long goodbye: can you recognize the theme?

On some other street, two people meet as in a dream —

[. . .] It’s too late to try, when a missed hello

Becomes a long goodbye.

(Copyright by U.A. Music Ltd.)

In simplest thematic terms, this is a commentary on the broken encounters that punctuate the film (and it should be noted that the personal pronouns become masculine whenever Clydie King sings the lyrics, thereby expanding their inclusiveness), beginning with Marlowe and his cat and continuing through virtually every subsequent relationship charted in the plot. As with Cohen’s songs in McCabe, the relevance to the action is fluctuating but dynamic in relation to our responses, and the same words can suggest different things at different times. In more directly operative terms, the song functions as follows:

1. As a piano improvisation (by the Dave Grusin Trio) in the opening scene, before the actual theme is stated; as Marlowe is woken by his cat and tries to persuade the latter to eat something, he can be heard humming, singing (‘Can you recognize the theme?’) and whistling various fragments, completely out of synch with the piano and in a different key.

2. Sung by Jack Sheldon as the credits come on, while Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton) drives away from the Malibu Colony (and is momentarily entertained by the gate attendant’s Barbara Stanwyck imitation), in a medium-tempo, somewhat Sinatra-like version.

3. Sung by Clydie King (beginning a fresh chorus) in a slower, more moody and lyrical version as Marlowe pulls up at a supermarket to buy cat food, her chorus continued by

4. A soupy muzak version of soaring violins, parodying conventional Hollywood mood music, as Marlowe enters the supermarket (where he’s told that he has left the car headlights on), which is continued by

5. Sheldon’s version, while Terry drives towards Marlowe’s house, proceeding through the next-to-last bar of a chorus, which is completed (and a new chorus begun) by

6. The muzak version in the supermarket (Marlowe to clerk: ‘You don’t happen to have a cat by any chance –‘ Clerk: ‘Whadda I need a cat for? I got a girl’), continued by

7. Sheldon’s version over Terry driving, which is in turn continued by

8. Grusin’s piano improvisation as Marlowe returns home, again humming and singing parts of the tune-out of synch, in a different key — along with phrases of his own (‘I love the cat’).

Subsequent uses include (among many others) a statement of the theme by guitar and castanets over Marlowe and Terry’s drive to Mexico; the first four notes sounded whenever Eileen and Roger Wade’s gate bell is rung; a version by Morgan Ames’ Aluminum Band continuing Clydie King’s rendition during the first scene with Marty Augustine, when the music first comes over a car radio, then is made to sound as though it is coming from the house of Marlowe’s hippy neighbors; back in Mexico, as a funeral dirge played by the Tapoztlan Municipal Band while Marlowe speaks to the local coroner; a loud, chaotic and sloppy jazz version played and sung by guests at the Wades’ party in Malibu (a scene of social chaos gravitating around Roger Wade, who is emotionally going to pieces); and sung with a slight Jewish lilt by Marty Augustine in his office as he waits for Marlowe to arrive.

The continuities and discontinuities that are established or implied in Nos. 1-8 –- between Marlowe and Terry, home and supermarket, one car’s trajectory and another, or one ad lib version over another-are not merely reflections but active instruments of the divisions being set up between these discrete entities, at the same time that a common tune is binding them all together. And the spectator’s relationship to the action is being further played with by the multiple shifts in the music’s volume throughout most of the above examples, as melody and/or words fade in and out of the soundtrack in relation to the dialogue, passing from ‘foreground’ to ‘background’ in a manner somewhat analogous to the camera movements in so far as they repeatedly redefine our focus on and distance from the events taking place — thus continually altering and varying our grasp of them. We are required, in other words, to improvise our own ‘Long Goodbye’, both figuratively and literally, in order to establish our proximity to all the others.

The shifting volumes of other sound elements — the miaow of Marlowe’s cat, the voices of his spaced-out neighbors – are simultaneously altering our impressions of spatial depth and physical separations in these scenes, as is the sound editing of Marlowe’s police interrogation, which cuts back and forth between the tinny reverberations in the room he is being ‘secretly’ observed from to the more full- bodied sound in the room that he occupies.

But the spatial and spiritual distances suggested in the above are modest indeed compared to those which accumulate in the movie’s later scenes, beginning with the Wades’ disastrous party. In the scenes that follow — Roger’s suicide, Marty Augustine’s threat to castrate Marlowe, Marlowe’s frantic pursuit of a glassy-eyed Eileen Wade until he is run over, his regaining consciousness in the hospital — the sharp divisions between characters reach an intensity that suggests a rapid escalation of neurosis to schizophrenia, a state of total dissociation. This is expressed not only through a shallow sense of space in certain shots (Marlowe and Eileen rushing into the waves after Roger, Marlowe’s subsequent chase after Eileen), where characters appear to be traversing enormous distances without advancing anywhere, but even further in the loud, bouncy, cheerful and utterly autonomous jazz piano version of the theme which accompanies Marlowe’s frenzied pursuit of Eileen. When he is hit by another car, the sound suddenly dovetails into a few raucous bars near the conclusion of Sheldon’s vocal version, with a trumpet blaring over the voice; this in turn is quickly overtaken by a cacophony of overlapping sirens that fade into a dead silence broken only by maniacal, distant screams from other rooms in the hospital where Marlowe wakes up.

For all its jokey overtones, the scene which ensues is decidedly the most nightmarish in the entire film. On the bed opposite Marlowe’s lies a figure wrapped mummy-like, from head to toe, in bandages. After coming to his senses, Marlowe cracks to his room mate, ‘You’re gonna be okay — I seen all your pictures too’ and starts to leave the room, until the figure grunts at him incoherently but insistently, beckoning him over. ‘Hey listen, you tell that guy that it don’t hurt to die’ Marlowe remarks to the virtual corpse that might as well be him — indeed, is him if we consider how Marlowe stalks senselessly through the remainder of the film. ‘Hey, that’s the smallest one I’ve seen,’ he goes on, picking up the mummy’s miniature harmonica. ‘No, listen, I can’t,’ he explains, ‘I gotta tin ear.’ He blows a plaintive whine on the harmonica, adds, ‘I’ll practice — see you later,’ and beats his retreat from the room and his dormant doppelgänger, evading a nurse with the declaration, ‘I’m not Mr. Marlowe, this is Mr. Marlowe here’ with another distant scream of pain from another room heard over his parting words.

In this crucial scene, we have Altman’s ‘universe’, themes and formal procedures reduced to their barest expressions. And if the harmonica and Marlowe’s cryptic adoption of it — he is blowing on it again in the movie’s closing shot — immediately recalls the harmonica wails of Jean-Pierre Léaud in Jacques Rivette’s Out 1 and Out 1: Spectre for its reduction of communication itself and the production of ‘meaning’ to stark essentials, the relationship may not be entirely fortuitous. Rivette has recently expressed an interest in Altman’s work which began with The Long Goodbye; and the behavioral comparisons of Juliet Berto and Dominique Labourier (or Bulle Ogier and Marie-France Pisier) in Rivette’s Céline et Julie vont en bateau are not wholly irrelevant to those of Elliott Gould and George Segal (or Ann Prentiss and Gwen Welles) in California Split, however much more simplified and ‘protected’ the Altman-conducted improvisations may be.

Central to the concept of modernism in all the arts is the idea of collaboration — the notion that artist and audience conspire to create the work in its living form, that the experience of making it is in some way coterminous (if far from identical) to the experience of hearing, seeing or reading it. Even at his most venturesome and ‘experimental’, Altman cannot be described as a director who pursues this notion unequivocally and consistently, in the sense that Tati does in Playtime (through visual options) and Rivette does in Spectre (through interpretative options) ; considering the fairly constant way he has remained active in the commercial cinema since MASH in 1970 — and all the conditions that this fact implies — he cannot really be considered in the same league at all. But virtually alone among his peers, he has opened up the American illusionist cinema to a few of the possibilities inherent in this sort of game — played for limited stakes in controlled situations, but played none the less.