From Film Comment. — J.R.

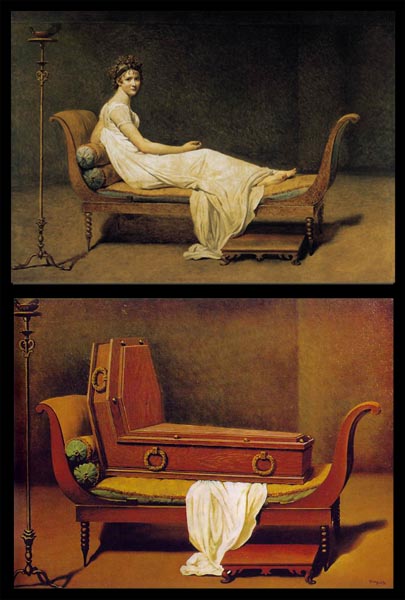

JULIEN: Have you ever thought that the true reverse angle, as one says in cinematography, of [Magritte’s] Madame Récamier, is the public much more than the painter at work?

— From the script of L’AUTOMNE

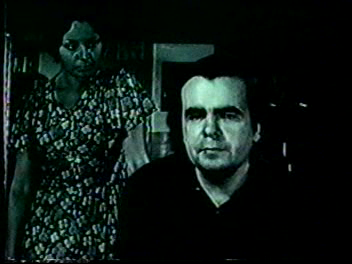

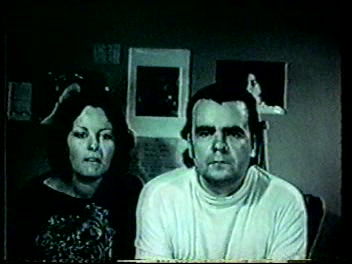

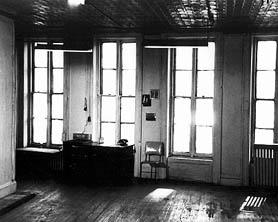

All but the last eight minutes or so of Marcel Hanoun’s L’AUTOMNE (AUTUMN) is filmed from a single fixed camera angle, which corresponds to the viewing screen in an editing studio. From this vantage point, we can see a few things posted on the opposite wall, such as photographs of actresses from other Hanoun films, a strip of film, and an Anthology Film Archives schedule. We can also see Julien (Michel Lonsdale), the filmmaker, and Anne (Tamia), his assistant, working at the editing table on the unseen film-in-progress, which is equated in a rather disquieting way to us, the spectators. Julien or Anne may depart from the frame for minutes at a time, when they turn off the lights in the studio to work on the film, we cannot see them, but the film remains.

The film is rich in paradoxical equations and relationships. In a text serving as an introduction to the published script (available from Ça, Editions Albatros, 14 rue de l’Amorique, Paris 15, for 6 francs; a 64-page book about Hanoun’s films for 4 francs has recently been put out by the same publisher), Hanoun notes that the film can be summed up in the following formula: SCREEN = CAMERA = AUTEUR = SPECTATOR = FILM. The single factor inextricably binding us to Julien and Anne is the film we cannot see; at the same time, of course, they cannot see us. We can hear parts of the soundtrack from time to time, but because of our vantage point, this inevitably accompanies our images of Julien Anne, not those of the film they are editing.

Then, roughly eight minutes before the end of L’AUTOMNE, we see and hear Julien speaking to his producer on the phone and telling him that only eight minutes of the film remain to be edited. And shortly thereafter, we see these eight minutes: an inventory of autumn foliage filmed in color from the window of a moving car accompanied by Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde. (We have already heard some of this music, and Julien’s description of the sequence, somewhat earlier in the film.) For its almost ceremonial fluidity and purity, this lyrical cadenza recalls LE CHRIST DANS LE CITÉ and LA MUERTE DEL TORO (both 1964) , two beautiful shorts by Hanoun that were shown with L’AUTOMNE during its brief Paris run….At the end of this sequence, the camera zooms backwards from the screen at the editing table, gradually revealing the studio in reverse angle for the first time, with the last image of Julien’s film framed directly in the center. This time the “missing element” in the equation is Julien and Anne, who have left the studio: assuming their previous position, we stand back from our/their creation, and our perception of it is no longer unmediated.

I’m not at all sure about the interrelationships between L’AUTOMNE and Hanoun’s three other features named after the seasons , but I wonder if the notion of a Greek tetralogy might be relevant: if L’ÉTÉ (1968), L’HIVER (1969) and LE PRINTEMPS (1970) can be seen as tragedies -– I haven’t seen the first, so I’m speculating -– L’AUTOMNE (1971-72) might be regarded as a satyric drama. The ironic and self-reflexive stance of the latter film also suggests an encounter between Hanoun’s own specific style and intelligence with some of the preoccupations of the North American “structural” film –- an encounter anticipated, incidentally, in the program of Anthology Film Archives. Quite apart from the rigorous delimitation of space, what is the final reverse-zoom if not an abbreviated version of Michael Snow’s WAVELENGTH run backwards?

***

Otto Preminger’s SUCH GOOD FRIENDS finally arrived in Paris around the same time as the September-October Film Comment, where Elliott sirkin writes the film off as a “grisly bust’ and gross betrayal of Lois Gould’s novel. Not having read the novel, I can hardly quarrel with Sirkin’s strictures about the adaptation; he went to see a film of the book while I went to a Preminger film, which led us to widely different conclusions. For my part, I can only continue to speculate about what’s happened to Preminger’s work since he took acid a few years back (see Gerald Pratley’s silly paperback on Preminger, pages 162-163), in preparation for SKIDOO.

I don’t happen to consider SKIDOO or TELL ME THAT YOU LOVE ME, JUNIE MOON successful works by any stretch of the imagination, but they’re endlessly fascinating aberrations: particularly the first, which enlists a legion of Fifties TV corpses into an amalgamation of every conceivable Hollywood genre to illustrate a contemporary fable about hippies taking over the world, which is ruled by God (a Mafia chieftain improbably played by Groucho Marx). In a film with tonal clashes and mixtures that often gel about as well as gin and molasses with a dash of ketchup, it seems entirely appropriate that the principal musical number, rendered as an acid version of two prison guards (one of them Fred Clark, in his last movie role) be a Garbage Can Ballet. A comedy without laughs, just as the next film is a tragedy without tears -– too many tragically old faces in the first, too many comically young faces in the second -– but in both cases, it is the overtones that make them so unusual and interesting. Indeed, if these films made more cohesive sense, I suspect that they’d be lesser works.

It’s questionable whether Preminger has ever been guilty of “good taste” in the Lubitsch tradition (THAT LADY IN ERMINE, which he took over from Lubitsch, is tackiness incarnate), but the difference between his pre- and post-SKIDOO work is that in the former, his uneven taste was still held back by a certain amount of decorum. The undeniable aggression of Preminger’s last three films is largely a matter of the freedom gained by junking this decorum. Garishness becomes no longer an attempt at stylishness but a bitter fact of life, like a great deal of modern architecture.

If SUCH GOOD FRIENDS succeeds in turning this anguish into a workable style, this may be because it combines the genres of failed comedy and failed tragedy top create a comic tragedy that “works” -– a film that makes us want to laugh, weep, or scream, often at the same time, but never lets us settle comfortably into any reaction for long, forcing a virtual suspension of response that makes each scene an open and ambiguous narrative statement. A film whose harshest revelations are couched in and between strained attempts at New York repartee (e.g., the lunch scene between Ken Howard and Dyan Cannon) and the most vulgar burlesque imaginable (James Coco frantically removing his girdle while Cannon prepares to give him a blowjob, in a scene ending, the dialogue tells us, with him ejaculating on her nose —- “a particularly revolting sex scene,” Sirkin observes) is a closer and more just portrayal of the milieu it depicts than many spectators can apparently stand, because all of its most interesting details are disturbing, “unnecessary” overtones: the self-righteous delivery of a line by a black nurse turns a valid point into a gratuitous occasion for smugness; a wonderful short Jewish doctor delivers each gruesome medical verdict like a Reform rabbi counseling his congregation; tragedy improbably enters the scene with Coco cited above because all of its low-comedy maneuvers are shown growing directly out of shame and despair.

The shrill ungainliness and excruciation of such scenes is like a truth serum administered to Elaine May’s bantering script, making the film into an extraordinarily schizoid experience. The last scene, where Cannon disappears with her two sons in to Central Park, can be interpreted as the character’s triumphant “survival” if we listen to the song on the soundtrack, her ignoble defeat if we look at Cannon’s face. Putting these contradictory elements together, Preminger creates a cynical form of neo-realism that refuses to harmonize all his disparate ingredients into a comfortable conclusion. The blind listener will say “comedy,” the deaf viewer will say “tragedy,” but the spectator condemned to see and hear will have to settle, like Preminger, for something else.

***

SUCH GOOD FRIENDS seems to offend a lot of people because it “goes too far”; Jacques Demy’s new film, L’ÉVÉNEMENT LE PLUS IMPORTANT DEPUIS L’HOMME A MARCHÉ SUR LA LUNE(THE MOST IMPORTANT EVENT SINCE MAN WALKED ON THE MOON), rather offends me because it doesn’t go nearly far enough. As A MAN AND A WOMAN, BED AND BOARD, and LE SEX SHOP have all amply demonstrated, one culture’s middle-class pap can easily be transformed into another culture’s chic, as long as the language remains different (one reverse example: Aubier-Flammarion’s bilingual editions include Love Story along with Beckett, Blake, Goethe, Hawthorne, Poe and Shakespeare), and I wouldn’t be surprised if the same thing happened to this film, which also takes us on a short little ride away from convention that goes no further than the corner bistro before returning safely to hearth and home.

The “teaser” this time is the notion of a man (Marcello Mastroianni) becoming pregnant; the safety valve on the premise is that it turns out to be a false pregnancy, both literally and figuratively, so that we’re given a run for our money that can’t even properly be called a dry run. To make sure that we’re sufficiently distracted, Michel Legrand — who manufactures some of the best trash in the business –- provides the theme music, Catherine Deneuve plays the wife, and we get some of Demy’s customary coloring-book décor: long after I forget everything else about this film, I suspect I’ll still remember Claude Melki’s multicolored sci-fi flipper shirt. Mastroianni’s distended belly looks quite convincing, which made me wonder briefly if he might have prepared for the part by eating all of the Fauchon food supplied for LA GRANDE BOUFFE; that it proves to contain nothing but a scheme for getting us inside the theater probably won’t matter much to spectators looking for light, graceful, stylish, soporific entertainment.

***

A last-minute flash: Less than 24 hours after writing the above, I was able to attend a private screening of Fake, a remarkable new film by Orson Welles. I’m afraid at least one or two more viewings of the film will be necessary before I can determine whether it’s merely the least boring film I’ve seen in months or a great deal more than that. For the moment, steeped in the decidedly un-objective afterglow of sheer admiration, I can only stammer out a few points:

[2] A few rumblings have already been heard to the effect that Fake is “not really a Welles film”; don’t believe a word of it. It is true that he uses a lot of material shot by François Reichenbach, from a film aboutde Hory that was made before Clifford Irving’s own hoax was uncovered.(Other footage used includes excerpts from a sci-fi film — Earth vs. Flying Saucers, if I’m not mistaken.) But it would be inadequate to suggest that all he does with this footage is re-edit it. More precisely, he sets up a complex dialogue with and between various fragments of it, interlaces this with sounds and images of his own, and comes up with something entirely different….Another unwarranted dismissal would be to assume that it’s “just a documentary.” On its most serious level, it is an essay on cinematic illusionism expressed simultaneously by exploding illusions and reveling in them, mixing “fact” and “fiction” so subtly in some cases that it confounds our ordinary definitions of both terms, and creating as many Chinese-puzzle-paradoxes as a tale by Borges.

[3] The film begins, appropriately enough, with Welles performing magic to a group of children. With various forms of wizardry, he goes on to manufacture conversations with other people (de Hory, Irving) that never existed, counterfeit part of his own War of the Worlds broadcast, remake the newsreel opening of Citizen Kane, zip us around the Western Hemisphere — from his editing studio to Ibiza to Hollywood to Las Vegas and back again, with many side trips — without letting us pause for breath, make his leading actress (Oja Kodar) disappear, and levitate someone who may or may not be her grandfather (who also promptly disappears), The exhilaration of Fake derives not so much from the more overt tricks that Welles pulls — some of these we see through (and the biggest, alas, is given away by John Russell Taylor in the Autumn [1973] Sight and Sound) — but the pleasure that Welles communicates in performing them. Artifice and playfulness are the most prominent characteristics of his magic, and he makes them into primal emotions.

[4] I suppose what I like most about Fake is how deeply it digs into Welles’ sources, all the way back to the radio shows of the Thirties and the headlong exposition and comic-strip velocity in his early features; the crazy-quilt cutting patterns, and the comedy too — I don’t think he’s made me laugh so much since his films in the Forties. The more somber aspects of his later work, from Touch of Evil to An Immortal Story, are mainly reflected in a few terse aphorisms and anecdotes. Shakespeare aside, it is the most verbal film he has made since he left Hollywood, and its sustaining thread is his symphonic voice…. The most moving moments all come from recreations of Welles’ past: recounting his experiences as a bohemian painter in Ireland at 16; reflecting on the consequences of The War of the Worlds with devastating irony (”I didn’t go to jail — I went to Hollywood”); picking up the lift in Arkadin’s accent when he imitates a Hungarian; and in a particularly ghostly moment, turning luminous long shots of Chartres into another version of Kane’s mansion….Whether or not Welles has actually reinvented his toy train in a Paris editing studio and various other locations, he conveys so much joy in the very act of movie-making that he momentarily persuades us of the fact.

[5] “Cinema is the most beautiful fraud in the world,” Godard says in Le grand escroc. Welles doesn’t include this in his collection of epigrams, but he brought the statement back to memory and then made me wonder whether Godard might have lifted it from somewhere else. Why not?

Department of Mystification: Two days after completing and sending off the above, Les Films du Prisme sends me a fiche technique of the new Welles film. According to them, the title is Question Mark, Welles and Reichenbach share the director’s credit, and the script is by Oja Palinkas (Kodar), the leading actress. Elmyr de Hory and Clifford Irving (but not Welles) are listed as the leading actors. On the credits of the film that I saw, the word Fake appears, followed by a question mark, and afterwards the title, “a film by Orson Welles.” For the time being, I am content to call it The New Orson Welles Film, co-directed by Irving and de Hory, written by Jorge Luis Borges, and produced by Howard Hughes…. As Welles remarks about Chartres, the most important thing is that it exists.