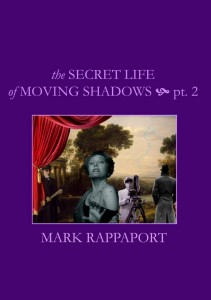

The following is Mark Rappaport’s Introduction to his new collection, The Secret Life of Moving Shadows, available now from Amazon as an e-book (in two parts, available here and here — a necessary division made in order to keep the book’s illustrations the proper size), reprinted here at my suggestion and with Mark’s permission.

I was delighted to learn, shortly after posting this for the first time, that the Criterion Blu-Ray of All That Heaven Allows includes Mark’s 1992 feature Rock Hudson’s Home Movies as one of the extras. More recently (in 2021), I learned to my delight that Fox Lorber has picked up a sizable portion of Mark’s oeuvre, for live screenings as well as digital releases. — J.R.

This is a collection of essays I wrote over the last several years. If there is no unifying theme to them or a through-line, let me just say that they were all written because I wanted to write them and I felt I had something to say about each of the films or subjects or ideas that I hadn’t seen adequately dealt with elsewhere. In almost every case, the idea came to me in a flash—either inspired by something I read or while watching a movie. If there is anything that unifies them, it is my particular taste in movies and my particular and maybe even peculiar take on them.

Writing about movies is very tricky. You’re trying to describe things that can’t be described. It’s like writing about painting or sculpture or music or dance or architecture. The vocabulary at hand for dealing with an ineffable and invisible ghost that refuses to be captured or surrender itself to your words is sorely lacking—no matter how persuasive you are. You are trying to reduce images to sentences, sweeping camera moves to paragraphs, soaring emotional crescendos to punctuation. Something is always missing and you’re never quite getting to the heart of the matter. The essence of the film is elsewhere. You’re trying to pick up sand with a fork, you’re trying to extract the soul from the body with a pair of tongs and tweezers. You’re lunging to embrace shadows that vanish just when you think you are about to touch them.

Fifteen years ago or so, I had an idea. I asked a friend of mine who was a technogeek and could answer any questions about computer-related imagery if there was any way I could grab images from laser discs and put them on my computer. She said she had no idea. The best she could come up with was freezing a frame that I wanted while it was playing on the TV, taking a picture of that frame, cropping the TV out of the frame, etc. Too complicated for what I wanted to do. But things changed very rapidly. Technology caught up with my needs and desires. Now there are software programs that enable you/me to grab frames from DVDs and import them into text files. Even though I had been hoping that someday something of that sort might exist, that doesn’t exactly make me a visionary. Visionaries are made of sterner and more technically acute stuff. Any more than I was a visionary in the late sixties when I recorded, on cheap tape recorders, parts of sound tracks (from TV, again) of scenes from my favorite movies — to listen to over and over. Once again, I was anticipating something that I didn’t know was in the wind and could only, at best, hope for. I can’t claim to have invented VHSs or DVDs but I sensed the need for, well, let us say, something that someone with the technical know-how would turn into a major electronic appliance that many of us would subsequently benefit from and enjoy. I was just an unfulfilled consumer waiting, waiting, waiting for an invention that would answer unasked, not-quite articulated, but nevertheless fervent prayers.

I do know one thing, however — the invention of VHSs and especially DVDs has been a great boon to people who write about films. It used to be that you were at the mercy of your own faulty memory. Is this the way the frame looked? Or did it look like that? What was the exact dialogue that that character said? Did this action come before or after the climactic scene? Did the music start before the dialogue or after it or during it? Does she enter from the left side of the frame or the right side—I can’t actually remember. And another thing — when reading about films, you were always at the mercy of the writer’s inaccurate descriptions of what he or she thought he saw. Or the way she left out things when she described them. Or got the order wrong. But even worse that, when the reader read the imperfect descriptions and wasn’t as familiar with the film as the writer was, the reader would try — in vain — to summon up the images in his head that the writer tried — in vain — to describe. All to very little avail. There were too many variables for this strategy to work. If you weren’t as familiar with the movie as the writer was, you may have been getting the point, but just barely.

Modern technologies have changed all that. Or have offered the possibilities of changing all that. Now you can use stills from the very films you’re talking about so that no one is in doubt as to what it is that you mean. If you analyze a scene, you can convincingly offer examples of your claims. The illustrated text can function as a much more potent argument than lofty, semi-accurate descriptions, which are, at best, highly subjective and can usually be proven to be very flawed as well. In fact, the new technologies have permitted and encouraged a new kind of writing in which the written word is the handmaiden of the images they attempt to clarify. This is not nothing.

For me, this has provided a great deal of freedom. One can talk about films in a very concrete way and give concrete examples. One can discuss films in their own terms. In fact, several of the pieces in this collection exist only because this technology exists. Articles like “Lola Montès: A Life Behind the Footlights,” “Fritz Lang’s The Woman in the Window,” “Hitchcock Goes to the Movies,” “Tati, Bresson, and the Gag” and especially “The Secret Life of Objects” were written only because it was possible to illustrate them with frames from the films they refer to. Without these images, the articles would be meaningless. Not only could they not exist, they couldn’t even have been imagined. So, whatever grievances one has about the proliferation of electronic technologies and how they have debased our lives — and they are legion—I for one am grateful, as a movie-lover, a filmmaker and a writer about film, how these particular technologies have made writing about film more possible and, dare I use the word, more visible.

More to be thankful for, regarding hitherto unimagined technologies. The fact that delivery systems have also changed makes a huge difference in the way pieces can be written What book publisher, even today, would dream of publishing a specialized book with so many pictures, even though printing techniques are now also more flexible, and cheaper and easier to print than they used to be? Internet publishing and now e-books have added something new to the mix. You’re seeing the images, not in poor quality reproductions, on less than ideal paper but in the same quality that they were plucked out of the films in which they were once (and still are) nestled.

There are drawbacks, yes. One still can’t, to my knowledge, format e-books so that one can look at two images side by side. Very important for comparing and contrasting, looking at two frames together. Unfortunately, one has to stack the images vertically. This is a wrinkle that will be ironed out someday — probably sooner rather than later. And someday soon, if it’s not happening already, one will be able to insert into e-books very precise clips that one has chosen from films to enable the reader/watcher to participate more fully in the discussion. When the reader/viewer can actually see what the writer/viewer is talking about, we will all be talking the same language. We will be sharing the same experience. So, I thank the technodieties who have made this new kind of writing possible as well as those, probably in an adjacent neighborhood on Mount Parnassus, who’ve made them accessible. Let’s hope that snipping out clips from films will soon be available to e-book users and the film writers who want to present them, as if they were evidence in a courtroom, will be available to all of us, sooner rather than later. This is not necessarily, to counter any unraised objections, a lazy way to write about films. In fact, I’m more and more convinced that this is the only way.

In any case, it’s a little like when you were a kid, reading those magazines and newspapers that prided themselves on providing easily understandable pictures rather than cluttering their pages with unwieldy texts. Who would not agree, especially people who love movies, that, given a choice, it’s more fun to look at the pictures?

March 2014