From the Chicago Reader, June 20, 2003. The posthumous Schuller-conducted premiere of Epitaph, incidentally, alluded to below, is now available on DVD, and is warmly recommended. — J.R.

Charles Mingus: Triumph of the Underdog

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Don McGlynn.

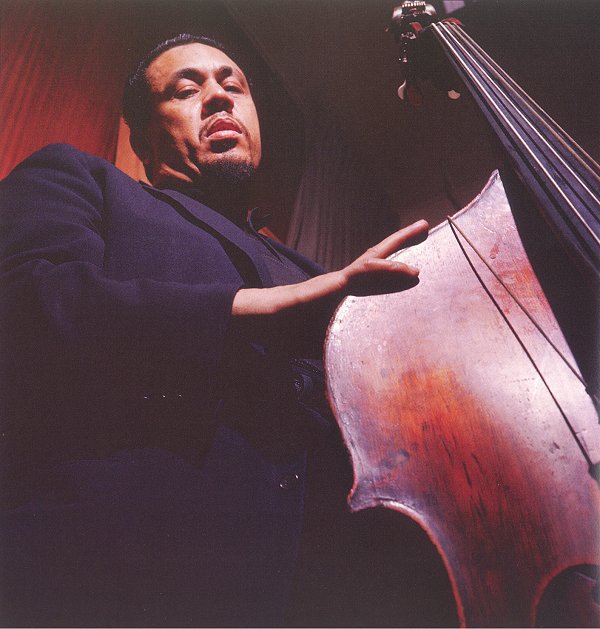

The sheer impossibility of encompassing jazz bassist, composer, and bandleader Charles Mingus (1922-’79) in a single film limits Don McGlynn’s ambitious 1997 documentary, Charles Mingus: Triumph of the Underdog, from the outset. Which doesn’t mean you shouldn’t see it — it’s playing at the Gene Siskel Film Center, and Mingus’s second wife, Celia Mingus Zaentz, will lead a discussion after the June 27 screening — but if you don’t already know something about the man’s music this may not be the ideal place to start. I’d recommend instead one of his best early albums — The Clown, Tijuana Moods, East Coasting, Mingus Dynasty, Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus (the best one with Eric Dolphy), or Mingus at Monterey.

No single book has succeeded in doing full justice to Mingus either. Maybe it’s because he had a genius for straddling musical categories such as traditional, modern, avant-garde, jazz, and classical (as Gunther Schuller points out in one of this film’s interviews, Mingus studied Arnold Schoenberg’s music in his teens, during the 30s, when few people here were familiar with it). Maybe it’s because he straddled existential categories such as art, politics, and life, and emotion and thought. In other words, his personality spills over the edges of the kinds of definitions most books and films rely on for portraiture. Even the ethnic mix of his background — black, Chinese, and Swedish — confounds the usual descriptive labels, much as his seamless fusions of gospel, Dixieland, swing, bebop, R & B, and classical confound the generic formulas.

The emotional and thematic continuities between some of Mingus’s earliest and last compositions are fully apparent in Triumph of the Underdog. In all his best pieces the sound of passionate and unbridled weeping, sobbing, and sometimes wailing that’s so apparent in the solo voices of musicians such as Bessie Smith or Charlie Parker is expanded into rich and complex ensembles without any emotional loss. And it’s apparent in even fleeting snatches of his music. Yet the task of capturing the dimensions of such a man in a single descriptive work remains formidable.

Let’s start with the books. Mingus’s eccentric autobiography, Beneath the Underdog (1971) — reportedly a pale shadow of the original manuscript — has lots of texture but comes across mainly as a collection of pungent fragments. Brian Priestley’s Mingus: A Critical Biography (1983) does much more with the music than the life. Janet Coleman and Al Young’s slim Mingus/Mingus: Two Memoirs (1989) contains the best prose but the fewest details. Gene Santoro’s wretched Myself When I Am Real: The Life and Music of Charles Mingus (2001) has the most details and the least sense of what to do with them; it often seems more concerned with precisely how much money the man made and spent than with the shape or feel of his music. Tonight at Noon: A Love Story (2002), by Sue Graham Mingus, his fourth and last wife, is invaluable for its glimpses of his last 15 years, especially his harrowing struggle with Lou Gehrig’s disease; understandably it has less to say about the 42 preceding years, apart from a wonderful catalog of the souvenirs collected in one of their flats.

The best brief description of Mingus may be the first paragraph of Coleman’s 67-page portion of Mingus/Mingus, if only because of the way it compresses Mingus’s range and mutability into what amounts to a miniature theme park or shopping mall: “I knew Charles Mingus almost twenty years, in various cities, at various weights, in canny and uncanny moments, and through various psychic and aesthetic incarnations. I bore witness to his Shotgun, Bicycle, Camera, Witchcraft, Cuban Cigar and Juice Bar periods, and was familiar with his Afro, Egyptian, English banker, Abercrombie and Fitch, Sanford and Son, and ski bunny costumes. I ate his chicken and dumplings, kidneys and brandy, popcorn and garlic, pigs, rabbits, godknows mice.” Even if I bump over the “godknows” in the final sentence, the abrupt swerves in logic and the spicing up of a stew that’s boiling over catch the quintessential Mingus.

Most jazz lives are so compartmentalized by club dates and recording sessions that the wider world is often held at bay. But Mingus insisted on bringing that world into his music every way he could — with his lyrics and agitprop recitatives, his song titles (“All the Things You Could Be by Now if Sigmund Freud’s Wife Was Your Mother,” “Meditations on Integration,” “Remember Rockefeller at Attica,” “Oh Lord, Don’t Let Them Drop That Atom Bomb on Me,” “Fables of Faubus”), his foghorns and whistles, his solos, and his “dialogues” with other musicians that approximate speech. One of my favorite comic outbursts, heard in Triumph of the Underdog, is a chant from Mingus that goes, “Who said Mama’s little baby loves shortenin’ bread? / That’s some lie some American white man said. / Mama’s little baby don’t like no shortenin’ bread, / Mama’s little baby likes truffles…caviar…African gold mines…African diamond mines.”

It’s hard to think of another major jazz figure who crossed over more into the other arts. Duke Ellington, Mingus’s principal influence, had plenty of his own encounters with film, theater, and dance, but I can’t imagine him writing poetry or taking photographs with the same abandon as Mingus. And even though in the early 40s Ellington mapped out a film project with Orson Welles as director and narrator, Mingus gave hints about what such a collaboration might have entailed when he said of Welles, “I dug his voice. It reminded me of Coleman Hawkins. You could hear it a mile away.”

It’s both an advantage and a disadvantage that Triumph of the Underdog tries to deal with the richness and multiplicity of Mingus by cramming in as much material as possible. The film starts off with a distracting flurry of sound bites and later even includes several portions of an earlier documentary, Thomas Reichman’s hour-long Mingus (1968) — a piece of cinéma vérité about Mingus getting evicted from his loft that also gives us long stretches of uninterrupted music.

By contrast, McGlynn’s 78-minute documentary rushes from one brilliant or telling fragment to another, yielding a meal that’s almost all hors d’oeuvres, with little of Mingus’s feeling for and mastery of larger forms. I had to wait nearly an hour to hear my favorite Mingus tune, “Peggy’s Blue Skylight,” played all the way through (in a rare up-tempo version, including its exquisite B theme). Mingus offers it only in successive bits intercut with the artist speaking to the camera in his loft or getting evicted. A better documentary might show us how the song’s opening phrase derives from bars 13 through 15 of Mingus’s lovely “Reincarnation of a Lovebird,” a demonstration of how key musical themes in his work can go through as many guises and settings as key characters in the novels of Balzac or Faulkner.

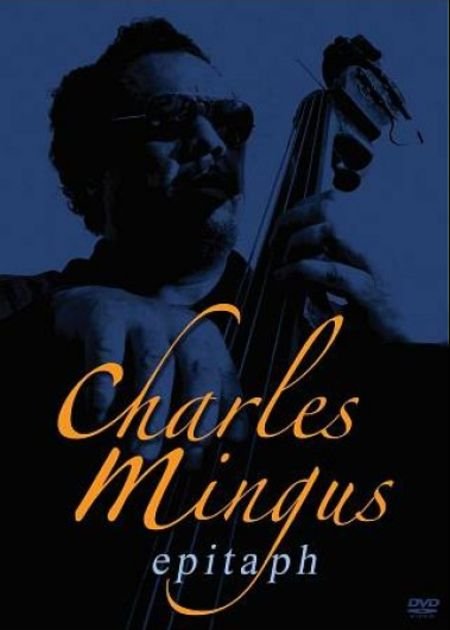

The superiority of Reichman’s documentary to McGlynn’s can be explained in part by their different agendas. Mingus is a rough-hewn but homogeneous portrait filmed on the run. Triumph of the Underdog, coproduced by Sue Mingus and McGlynn, boldly attempts a multifaceted summation, which is much harder to bring off. Even the title, with its reference to Beneath the Underdog, shows the strain of the effort. The triumph of course is posthumous and belongs strictly to Mingus’s supporters and audience. Inadequate preparation made his only attempt to perform his magnum opus — a work over two hours long that he eventually called Epitaph — at a 1962 Town Hall concert a nearly complete shambles; Sue Mingus calls it “the great disaster of his life.” So its successful performance (conducted by Gunther Schuller) at Lincoln Center in 1989 qualifies as a kind of ahistorical, postmodernist rewrite. Needless to say, our lives often consist of such wishful revisions (consider the recent invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, which both failed in their principal stated objectives — to capture Osama bin Laden and to eliminate Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction — and yet are celebrated in this country, though hardly anywhere else, as successes). But it’s decidedly un-Mingus-like to invite us to taste the victory without tasting equally the defeat.

Still, Triumph of the Underdog is sufficiently generous that it gives us some priceless moments, as when two of Mingus’s former wives, Celia and Sue — who inspired two of his loveliest tunes, “Celia” and “Sue’s Changes” — gleefully swap personal anecdotes. We also get vivid accounts of how Mingus managed to get fired from Duke Ellington’s band and how Charlie Parker managed to hire him by persuading him to quit his job at the post office. Regrettably, we don’t get any clips from John Cassavetes’s Shadows (1959), which fully matches the emotional tenor of its Mingus score. But the accumulation of other bits and pieces does convey what former Mingus sideman John Handy aptly calls his gusto. For the spread and reach of that gusto, search out the albums.