In a double whammy, Twilight Time has recently brought out splendid new Blu-Rays of two exceptional widescreen colonialist epics, Cy Endfield’s Zulu (1964, set in 1879) and Basil Dearden’s Khartoum (1966, set in 1883-1885). Both come equipped with extensive and informed audio commentaries by screenwriter Lem Dobbs and film historian Nick Redman, who are joined on Khartoum by film historian Julie Kirgo, a writer who also contributes essays on all of the Twilight Time releases, including these two. The first of these movies now strikes me as one of the very greatest of all war films (a genre that I’m not generally partial to), even when it presents combat as potentially noble, succeeding equally in intimate details and in spectacular overviews, whereas the second is at most an intriguing star vehicle for Charlton Heston (as British officer Charles Gordon) and Laurence Olivier (as Sudanese Arab leader Muhammad Ahmad, who dubbed himself the Mahdi), both playing egomaniacal religious fanatics whose two scenes together are the best in the film (although Ralph Richardson as Prime Minister Gladstone also gets in a few choice bits). The audio commentary in this case is notable for how critical and even disdainful it often is — something that I suspect Criterion would never tolerate on any of its own releases.

The audio commentary on Zulu offers a special and highly informative personal slant from Dobbs and Redman, both of whom grew up in England and have cherished their early memories of Zulu as a rousing boys’ adventure story; they also have a great deal to say about the actors, the stuntmen, and the John Barry score. Their overall experience of the film is quite different from mine, but I also suspect that theirs is far more typical. I was very late in catching up with Zulu because when I saw the trailer in New York during the mid-60s, during the height of the civil rights movement, I wrongly concluded it must be racist and stayed away. (The U.S. release was commercially unsuccessful, unlike its reception practically everywhere else, but I can’t tell from this distance of half a century how much of this might have been due to misleading advertising or the stateside social climate at the time.)

One aspect of the audio commentary that I would quarrel with is the role played by Cy Endfield, who initiated the project, coproduced it with Stanley Baker (one of its stars), coscripted it with John Prebble, and directed it. Given the unevenness of Endfield’s filmography as a whole (split between Hollywood in the 40s and early 50s and England after he became blacklisted, and where he initially had to work under pseudonyms and/or with fronts even there due to the Blacklist) and the relative inaccessibility of many of the titles, puzzled reactions to his career such as those of Dobbs and Redman are entirely understandable — including their conclusion, which I don’t share, that he wasn’t so much an artist as a craftsman (a judgment they also make about Dearden in their Khartoum commentary), possibly because they associate Endfield’s gifts as a superb action director more with entertainment than with art. They also speculate somewhat tentatively on the issue of whether or not Endfield’s Communist background informs the film. More generally, they keep using terms like “magic” and “alchemy” to account for why the various elements of Zulu come together as successfully as they do while resisting the possibility that an auteur or guiding force might have been involved.

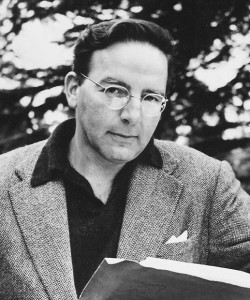

Because I had the rare privilege of spending a little over a day visiting Endfield and his gracious wife Maureen in rural England in mid-February 1993, I can add a few details pertaining to Zulu that might be helpful. I can’t claim that I got to know him well, and I subsequently discovered that he was less than candid about his Communist background (he claimed to me that he’d never joined the Party, which I later discovered to be false — a deception probably motivated by his late and unsuccessful attempt to relaunch a career in Hollywood by naming names, which I subsequently learned about from Paul Jarrico). But I can also testify that he was highly self-critical about most of his own films, and that Zulu was something he was justifiably very proud of. He cited in particular having spent four years shopping around his script until he finally found all the right conditions for making the film exactly the way he wanted to, and he was equally pleased about having learned how to compose his shots in 70-millimeter VistaVision. (To my mind, there is no way to describe his mise en scène and découpage here, including the beautifully composed pans and dollies, without reference to his artistry; and his handling of landscape is worthy of Anthony Mann’s.)

More generally, I would link the artistry of Zulu to its philosophical vision and not to politics (which is the terrain of Khartoum, as wittily established in Robert Ardrey’s somewhat stagey script) — a vision that encompasses a certain social philosophy, especially when it comes to class, but not a political view of its events. The Endfield films that have political slants are his American ones — especially The Argyle Secrets, The Underworld Story, and Try and Get Me aka The Sound of Fury — whereas his best British films all qualify in one way or another as social allegories.

The most obscure and least successful part of Zulu — the character of a hypocritical and hysterical local minister (played by Jack Hawkins) who has a sexually repressed daughter (Ulla Jacobsson) — may have been hampered by the fact that Endfield had wanted Robert Ryan for this part. For Endfield, the character as he conceived it represented the worst side of colonialism, and he does function dramatically as a villain (contrary to the claims of Dobbs and Redman, who argue that the film has no villain), yet the fact that his behavior implies some psychological backstory that is never articulated — in contrast to all the other characters, who don’t have any such requirements — is largely what makes him stick out like a sore thumb. [2/6/14]