From the Chicago Reader (September 14, 2001). — J.R.

The Vertical Ray of the Sun ***

Directed and written by Tran Anh Hung

With Tran Nu Yen-khe, Nguyen Nhu Quynh, Le Khanh, Ngo Quang Hai, Tran Manh Cuong, and Chu Ngoc Hung.

Last spring I was in Austin, Texas, on a film-festival panel about film festivals with the editor of a film magazine who’s also the author of a book on film festivals. “I don’t like foreign films or academic films,” he told me, a declaration that stumped me at first because it raised two vexing questions: (1) Why link “foreign films” and “academic films” as if the two had something intrinsic in common? (2) Had he seen at least one film from every foreign country in the world that produced movies and made his judgment on that basis?

After pondering other things he said, I came up with what I believe were the correct answers to both questions. (1) Foreign films and academic films were linked for him because both obliged him to think. (2) Of course not; what he meant by “foreign” was simply “not American.” Put these premises together and it’s clear he was saying he didn’t like movies that made him think, which is what non-American movies did — apparently even Bavarian porn, Italian splatter fests, and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. And in case you’re wondering how he could have written something called The Ultimate Film Festival Survival Guide, it caters to the American filmmaker, not the international filmgoer.

To be honest, I like plenty of movies that don’t make me think, but I like to get my mindless kicks from a variety of places — some from this country and some from elsewhere. The juiciest movie experience I’ve had in some time came from an arty Vietnamese item that’s a little bit like an opium dream, though a lot more sensual — The Vertical Ray of the Sun, as it’s called in this country. (In England it’s called At the Height of Summer, and in France it’s called À la verticale de l’été, which is somewhere in between the English titles.) I couldn’t follow much of the plot, and when I checked reviews by some of my colleagues I discovered that many of them had had the same trouble — though they seemed to derive as much pleasure from the film as I did. It would appear, in other words, none of us did much thinking, and we had a ball.

In 1994 I reviewed Tran Anh Hung’s first feature, The Scent of Green Papaya, and two years later I wrote about his second, Cyclo. I was persuaded that what enchanted me about his movies had something to do with thought, but at best I was only about a third right.

Tran was born in Vietnam in 1962 and moved with his family to Paris in 1975 — which I guess makes him doubly foreign (or is it foreign twice removed?). In any case, The Scent of Green Papaya, which he said was inspired by his mother, was set in separate households in Saigon in 1951 and 1961 but filmed in its entirety in a French studio. Cyclo, inspired by his father, was set as well as filmed in the present in the same city. I thought that both films redefined “inside” and “outside” — architecturally, socially, and psychologically.

If I wanted to be consistent, I could say that The Vertical Ray of the Sun does that too. Maybe it does and maybe it doesn’t, but it sure wasn’t what I was thinking about while I was watching it. It would be far simpler just to call Tran a mannerist and visual stylist like Josef von Sternberg and leave it at that.

The story has something to do with three sisters and a younger brother living in close proximity to one another in Hanoi; the brother and his slightly older sister share the same small apartment and at times the same bed. (They’re not quite — at least not yet — an incestuous couple, but the sister seems intrigued and amused by the idea.) It takes place over a month, beginning with the anniversary of their mother’s death and ending with the anniversary of their father’s death — which I suppose would make this something of a companion piece to Tran’s first and second features if I wanted to think about that. But I didn’t and don’t.

The movie opens with the brother, a movie actor, waking up one morning and rousing his sister (a waitress at the cafe across the street that one of their sisters runs), who’s sleeping on the other side of a curtain; they both do exercises to American pop songs, something that happens more than once during the movie. (Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground are particular favorites). This is fun to watch, but what’s most enjoyable isn’t the actors or the music — it’s the colors in the flat. Sections of the walls are painted yellow, green, a brownish mixture of the two, and blue, and there are all sorts of murals (including a humorous one of a gorilla in a shower), posters, and bric-a-brac — a Sternbergian sense of clutter, which is claustrophobic yet enchanted. (The cinematographer is Mark Lee Ping-bin, who shot Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love, and if you liked the colors in that film, you ain’t seen nothin’ yet.) Another pleasurable and Sternbergian pictorial effect, which occurs much later in the film and is more obviously fetishistic, involves a woman character’s gauzy black underwear draped over the front of a TV screen that shows only static. It’s meaningless, mindless, and so voluptuous that Tran couldn’t keep his eyes off it. Neither could I.

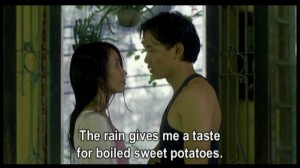

One reason Sternberg — another giver of mindless visual pleasure, including playful tricks with space — keeps coming to mind is that Tran has his own version of Marlene Dietrich: his wife and leading lady, Tran Nu Yen-khe, a lanky and mannered glamourpuss who plays prominent roles in all three of his features. A colleague of mine who’s a specialist in Asian cinema dislikes Tran’s movies in part because she dislikes his wife. This is probably as much a matter of taste as it is a matter of thought, but I think it has to be acknowledged that, like Dietrich, Tran Nu Yen-khe isn’t merely an actress — she’s part of her director’s decor and formal system. (The character she plays in this movie is called Lien, which happens to be the French word for link.)

Other significant characters in this movie include the two artists — a photographer and a novelist — the older sisters are married to, the son of one of these couples (called Little Mouse), the lover of the sister who’s married to the photographer, a friend of the brother, and a fisherman. There are other characters as well — not counting the dead parents — and I couldn’t begin to keep up with them all. But I didn’t care very much, except that I knew I was supposed to review this picture and I didn’t want to feel I’d been derelict in my duties. Then I decided that my main duty was to give up on the story — or at most visit it from time to time — and wallow in the mindless visuals, which were what I cared most about anyway. So to come back to my former copanelist, he can have his Kevin Smith fart jokes — or whatever it is that guarantees his unbridled fun at the movies. I’ve got my Tran Anh Hung highs, and there’s nothing remotely academic about them.