From the April 8, 1994 issue of the Chicago Reader. When I reprinted this article in my 1997 collection Movies as Politics, I gave it a different title: “Polanski and the American Experiment”.

For me, The Ghost Writer is Polanski’s best film since Bitter Moon, and his most masterful, although his subsequent Venus in Fur and Based on a True Story, both more subdued and subtler, are more interesting, especially as thoughtful autocritiques. — J.R.

**** BITTER MOON

Directed by Roman Polanski

Written by Polanski, Gerard Brach, John Brownjohn, and Jeff Gross

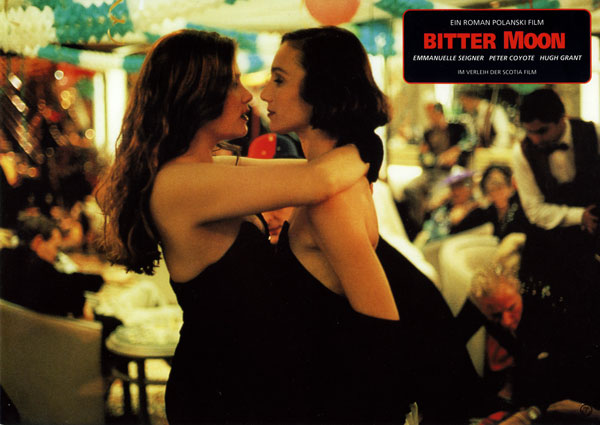

With Peter Coyote, Emmanuelle Seigner, Hugh Grant, Kristin Scott-Thomas, Victor Bannerjee, Sophie Patel, and Stockard Channing.

Fairly late in What? (1973), Roman Polanski’s least seen and least critically approved feature — an absurdist, misogynist, yet oddly affectionate ‘Scope comedy filmed in the seaside villa of its producer, Carlo Ponti — the bimbo American heroine (Sydne Rome), an Alice set loose in a decadent wonderland belonging to a dying millionaire named Noblart, wanders for the second time into a living room where she encounters a middle-aged Englishman. Once again this Noblart employee bemoans his arthritis, cracks his knuckles, then sits down at a piano to play the treble part of a Mozart sonata for four hands. Immediately recognizing the piece, she joins him, performing the bass part. After a rose petal drops from a bowl of flowers on the piano onto the keyboard, which also happened before, the wide-eyed heroine has an epiphany:

“It’s so strange — this keeps happening to me more and more often. You know that strange feeling that all this has happened before?”

“You mean deja vu?”

“No — not exactly.”

“Yes — that odd feeling that the moment we’re living now we’ve already lived before.”

“Sort of. But in this case it’s not just a feeling. This really has happened before.”

“Not in exactly the same way, though.”

“Yes, exactly: your knuckles — Mozart — the rose petal.”

“It wasn’t the same, I tell you. You can’t bathe twice in the same river because it’s never the same river — nor the same bather.”

Sometime between my first viewing of Polanski’s Bitter Moon, at the Toronto film festival last September, and my second, late last month, What? became available on letterboxed video at Facets Multimedia, and I had another look at it. (Before this, it had only been available in an atrociously recut and shortened version, marketed as a porn item called Diary of Forbidden Dreams.) Though the much less ambitious What? is lighter in tone and accomplishes a good deal less than Bitter Moon, it is still a crucial precedent, not only for its highly personal musings and self-reflections and its frank depiction of kinky sex, but also for the distinctive way it treats these matters formally, using an intricate rhyming structure in which everything of importance seems to happen twice — though “not exactly.” There are even textual connections between the movies: at the end of What? the heroine, departing on a truckful of pigs in a rainstorm, yells out to her lover (a pimp played by Marcello Mastroianni) that she may be headed next for Istanbul. That’s where two of the major characters in Bitter Moon, traveling on a luxury liner on the Black Sea, are headed; and Bitter Moon like What? ends with a rainstorm. (On the other hand, the thematic variations in What? are basically formal, whereas those in Bitter Moon are primarily emotional.)

Moreover, What? received the same sort of apoplectic critical rejection in some quarters as Bitter Moon has, no doubt for related reasons. Back in 1973, the International Herald-Tribune reviewer was so beside himself that he got the title wrong and reviewed What? as Why?, and in the New Republic last month Stanley Kauffmann, reviewing three recent Hugh Grant films, referred to Bitter Moon as “swill,” ranking it far below Three Weddings and a Funeral and Sirens.

Different strokes for different folks: for all the qualities of these light comedies as entertainment, neither of them qualifies as a complex work of art. Personally I find Bitter Moon riveting and energizing as few other recent movies have been, but I can guarantee that you won’t emerge from it with any songs in your heart or any cares and worries lifted; in fact, it’s blacker and in some ways bleaker than any Polanski movie to date. It’s also probably his best movie since Chinatown (1974), made only four years before he fled the United States.

Although Polanski regular Gerard Brach worked with him on the scripts of both What? and Bitter Moon, the latter film has two other writing credits as well, and is based on a French novel of the same title by Pascal Bruckner, which I haven’t read. Perhaps just as pertinent is what happened to Polanski between the two films. After pleading guilty to having sex with a 13-year-old girl and submitting to six weeks of “psychiatric evaluation” in a California state prison — and fearing an extended sentence, since the press was having a field day with his case — he escaped to Europe, where he’s lived ever since. None of his three subsequent movies — Tess (1979), Pirates (1986), and Frantic (1988) — has had a fraction of the success of his two Hollywood hits, Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and Chinatown. In the late 80s he married Emmanuelle Seigner, a French actress roughly half his age, the leading lady in both Frantic and Bitter Moon; about a year ago they had their first child, a daughter. (His former wife, Sharon Tate, was pregnant when slain in the brutal 1969 Charles Manson murders.)

In short, you might say Polanski has certain things to feel hopeful as well as bitter about: he may have a reputation as a pervert and be unable to return to the United States, but he has also remarried and recently become a father. All these things are clearly inscribed in Bitter Moon, a film that seems virtually driven by a desire to settle Polanski’s various accounts — entailing an autocritique that’s as ruthless and scathing as any committed to film, a portrait of Polanski’s own macho perversity calculated to produce shudders.

The brilliantly designed and controlled structure of Bitter Moon is above all novelistic, with particular reference to the 19th-century novel (recall that Tess is an adaptation of Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles). This tale-within-a-tale is set on board a ship, which suggests Joseph Conrad, and told to a rather square and inhibited English Eurobond salesman named Nigel Dobson (Hugh Grant), who suggests Lockwood in Wuthering Heights. This framing device is central to the film’s meaning; formally, we get a taste of it even before the story begins, behind the opening credits: the camera moves back slowly from a view of the passing sea until a porthole gradually enters the frame and encloses the picture; then the camera moves forward again, past the porthole, and finally pans left to a young English couple standing on deck, Nigel and his wife Fiona (Kristin Scott-Thomas).

Celebrating their seventh anniversary, Nigel and Fiona are headed for Istanbul, and plan to fly to Bombay from there; clearly the idea behind the trip is to rejuvenate their marriage, although an Indian acquaintance on board (Victor Bannerjee), a widower traveling with his little girl, gently mocks Nigel’s notion of India as a place to find “inner serenity.” Later he remarks, “Children are a better form of marital therapy than any trip to India.” (The way third-world exoticism is enlisted to spice up sex, marital and otherwise, is a subtle but telling theme throughout the movie.)

When Fiona excuses herself to go to the ladies’ room, the camera remains on deck with Nigel — establishing at the outset that his is the controlling viewpoint in the framing story. Fiona fails to return, so Nigel goes looking for her and discovers that she’s helping a young French woman named Mimi (Seigner) who’s apparently fainted. That night, after Fiona retires early to their cabin, Nigel finds Mimi in more glamorous attire in the bar, dancing alone to “Fever.” After she briefly flirts with him, then sarcastically rebuffs him as she leaves, pronouncing him dull, he encounters her husband, a wild-eyed American named Oscar (Peter Coyote), seated in a wheelchair on deck. Immediately picking up on Nigel’s attraction to Mimi, Oscar says, “Beware of her — she’s a walking mantrap,” then adds, indicating the wheelchair, “Look what she did to me.” Getting Nigel to help him back to his cabin, which he explains is separate from Mimi’s, Oscar invites him in, baiting him with his curiosity about Mimi; handing him a drink, he proceeds to tell the first of what will be four lengthy chapters in the movie’s tale-within-a-tale — the whole story of his relationship with Mimi in Paris.

Oscar, an unpublished novelist living in Paris on a trust fund, expresses himself throughout in an ornate prose that is one of the movie’s most useful and ambiguous narrative devices. It’s often so purple as to seem bad writing, hence easy to dismiss (and tempting to hoot at); but it also fully expresses the reckless, romantic intensity of a bored sensualist who’s willing to delve into passions that Nigel — the squirming, voyeuristic surrogate for our own puritanical inhibitions — can scarcely even think about. This uncertainty about Oscar’s prose style extends to the story he’s telling: is it simple pornography or a cautionary moral tale, a turn-on or a turnoff — or something between the two? Nigel himself isn’t sure, and Oscar needles him about this in the same way that Polanski needles us, gleefully and sadistically poking holes in his/our hypocrisies. Compounding the uncertainties are Oscar’s problematic reliability as a narrator (which Mimi calls into question) and the fact that we can’t always be sure if the flashbacks we’re watching are exclusively Oscar’s account of events or Nigel’s imagining of them.

Each time we return to the events on board, in between Oscar’s chapters, the situation between Nigel and Fiona shifts correspondingly, as Nigel becomes more and more attracted to Mimi. So it’s clear early on that Oscar’s tale isn’t an idle amusement: it’s a narrative with immense consequences, and part of the film’s immense power as story telling is to convey this sense of urgency. You might say that like musicians Oscar and Polanski are playing on our uneasy curiosity, and the piece they’re playing is a four-part symphony in sonata form, complete with theme and variations. (Readers who don’t want any plot points given away are urged to check out here.)

The first movement details the birth of passion and the first flush of love between Oscar and Mimi — an erotic romance involving a chance meeting on a bus, Oscar’s efforts to find Mimi again, a second meeting, and a first date at a plush Thai restaurant, culminating in lovemaking at dawn in front of his fireplace. (If the heroine’s sexual escapades in What? recall the old Playboy comic strip “Little Annie Fannie,” this scene is virtually the Playboy philosophy made flesh, conspicuous consumption and all: as important as the fireplace is a carefully prepared but ignored breakfast tray.) Mimi promptly moves in, and what follows are a few sexual games; the first real hint of the darkness to come occurs only near the end of this movement, when Mimi begs Oscar to let her shave him with his straight razor and accidentally nicks him (a moment that recalls a scene between Lionel Stander and Françoise Dorleac in Polanski’s 1966 black comedy Cul-De-Sac.)

The second movement begins when Oscar describes a kinky turn in his relationship with Mimi: on a skiing vacation, she began urinating on the TV set in their hotel room, and he suddenly felt moved to lie under her and drink her urine. His description — we don’t see this scene — is a fair sample of not only his overripe prose but of the third-world trappings that seem increasingly necessary to their affair, already signaled by the Thai restaurant and Mimi’s candlelit performance of “exotic” dancing in the first movement. “I experienced the orgasm of a lifetime,” Oscar says to Nigel. “It was like a white-hot blade piercing me through and through. This was my Nile, my Ganges, my Jordan, my fountain of youth, my second baptism.” “Look,” Nigel says, “I think I’m probably as broad-minded as the next man, but obviously there are limits.” “Stop twittering, Nigel. I’m sharing a revelation with you, dammit. I’m trying to expand your sexual horizons.” This leads into a proper flashback of other kinky sexual games (Oscar’s straight razor is employed in one as a melodramatic prop) and the couple’s first crisis, when each provokes sexual jealousy in the other at a bar, followed by more sexual games, which now yield diminishing returns. (Though furnished with a recording of barnyard noises and a pig mask, Oscar comically deflates one fantasy by talking, implying that sexual fantasies can be undone by words. Yet it’s Oscar’s words that intensify Nigel’s attraction to Mimi; and between the third and fourth movements Mimi notes to Nigel of Oscar, “I leave the words to him. It’s all he has left.”)

In the third movement — ironically narrated while Oscar lies on his bed and Nigel sits in Oscar’s wheelchair — things get decidedly uglier. Oscar describes the decline of his sexual interest in Mimi, followed by fights, recriminations, and Mimi leaving him, then coming back and begging him to let her stay on any terms. The infidelity, mental cruelty, and other, escalating forms of humiliation her return unleashes in Oscar are truly harrowing, and the thematic variations that dominate this movement are largely deeroticized, ghoulish replays of previous events. At a breakfast in the first movement, Mimi splashes milk on her breasts for Oscar to lap up; the scene’s comic orgasmic climax is toast springing out of a toaster. At a breakfast in this section, Oscar is disgusted when Mimi drinks milk directly from the bottle, and the “comic” orgasmic climax of another scene comes when Oscar, being serviced by a prostitute, winds up choking her poodle. Finally, after Mimi becomes pregnant and Oscar forces her to abort the child, he proposes a vacation for the two of them in Martinique, then sadistically leaves her alone on the plane just before it takes off. (At this point we discover the source of the film’s title: “I could picture her looking out the window at that beautiful moon — the same one I could see, but it didn’t look the same to her. . . . To her it must have been poison. To me, sweet as a peach.”)

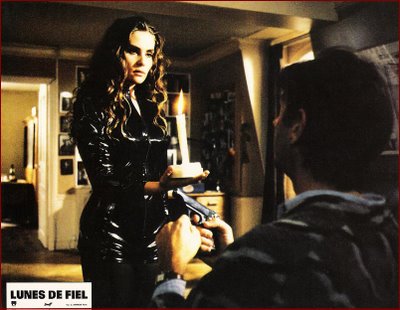

The final movement, which I won’t detail, occurs years later, when Mimi returns to Paris and takes her revenge on Oscar: paralyzed from the waist down, he comes fully under her sadistic control.

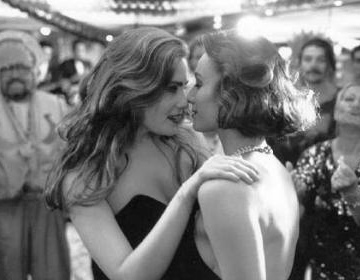

Where do we, as spectators, stand in relation to all this? I can’t vouch for the responses of women — this is essentially a tale told by one man to another, albeit one where the two women register much more sympathetically than the two men. But my guess is that male and female viewers alike stand in many places in succession, most of them pretty unsettling. And of course the shipboard machinations that surround these four movements, holding them in place and sometimes altering their meanings, offer another tense form of narrative striptease, mocking Nigel’s responses and our own while contributing a mordant counterpoint to the serial flashbacks. (At the climactic New Year’s Eve party on the ship, the increasingly cadaverous Oscar sports a fez — a final third-world reference in this account of the Ugly American abroad, exercising his much-vaunted freedom.)

As sexual games turn into games played for keeps and the abuser becomes the abused, every repeated event seems the infernal rhyme of its predecessor: Mimi kicking over Oscar in his chair as part of a playful sexual charade becomes Mimi viciously kicking Oscar in his wheelchair across the same room. Each lover winding up in a hospital bed becomes the occasion for the hatching of further macabre cruelties. Whether we take Bitter Moon as camp comedy or serious horror story, as pornography or cautionary moral tale, we’re implicitly rejecting half the experience the movie offers to go looking for solace in the other half, which we aren’t likely to find. What we have to settle for, finally, is Polanski’s dry, highly personal, and scary commentary on the perils of the American experiment itself, the so-called freedom of the individual played out in psychosexual terms and staged with French and English participants — a French-English coproduction whose ideal spectators are troubled Americans, and uneasy, childless lovers.