In his first three films Bela Tarr — conceivably the most important Eastern European filmmaker currently working — betrays an impatience with cinematic style, focusing almost exclusively on content, but that tendency was radically overturned with this 1984 feature, whose taste and intelligence are specifically (and exquisitely) cinematic and revealed Tarr as a master stylist. Set entirely in an apartment inhabited by an elderly woman, her son, his former teacher, the old woman’s nurse, and the nurse’s lover, the film consists mainly of intense two-part dialogues and encounters largely concerned with the old woman’s money. The remarkable use of color depends on a lighting scheme that divides most areas (and characters) into blue and orange, and the elaborately choreographed mise en scene is consistently inventive and unpredictable, making use of highly unorthodox angles and very slow camera movements. As in Damnation (1987), the mise en scene often seems to be composed in counterpoint to the action, but the drama itself (whose Strindbergian power and sexual conflicts are realized with an intensity and concentration that suggests John Cassavetes) carries plenty of charge on its own. 119 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the December 1, 1995 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

`

`

Would you buy a used car from Oliver Stone? Here’s another one (1995), guaranteed to last at least three weeks on the road, starring Anthony Hopkins as the man Stone and his fans have been calling a figure of Shakespearean proportions — which I suppose must make Stone a chip off the old bard. This runs 192 minutes and has very few jokes, but there are many references to Citizen Kane to put us in the right frame of mind. We’re asked to weep a tear or two for one of Stone’s first (as well as most recent) role models, not for any of his victims; even if he’s a flawed patriarch, he’s represented as being our very soul and tragic essence. Personally, I found even Clinton’s funeral oration more convincing. With James Woods, J.T. Walsh, Joan Allen (perhaps the only good excuse for seeing this film), Paul Sorvino, Madeleine Kahn, Bob Hoskins, E.G. Marshall, Mary Steenburgen, David Hyde Pierce, Ed Harris, and lots of kettledrums on the sound track to make us think about the destiny of nations. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 12, 1990). — J.R.

American TV watchers, eat your hearts out! These four selections from “Ten to Eleven” — a series of short, experimental “essay” films made for German television by the remarkable German filmmaker Alexander Kluge, to be shown here on video — are not always easy to follow in terms of tracing all their connections, but they’re the liveliest and most imaginative European TV shows I’ve seen since those of Ruiz and Godard. Densely constructed out of a very diverse selection of archival materials, which are manipulated (electronically and otherwise) in a number of unexpected ways, these historical meditations often suggest Max Ernst collages using the cultural flotsam of the last 100 years. Why Are You Crying, Antonio? relates fascism, opera, and domesticity; Articles of Advertising historicizes ads in a number of novel ways; Madame Butterfly Waits offers a compressed history of opera and its kitschy successors in pop culture; and the self-explanatory The Eiffel Tower, King Kong, and the White Woman makes use of comics, movies in the 1890s, a quote from Heidegger, and multiple images of the famous ape and tower. These are apparently fairly recent works. A Chicago premiere. (Randolph St. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 19, 2004). — J.R.

This experimental drama about the cruelty of a Rocky Mountain community toward a woman (Nicole Kidman) in flight from gangsters, shot with an all-star cast on a mainly bare soundstage, bored me for most of its 178 minutes and then infuriated me with its cheap cynicism once it belatedly became interesting — which may be a tribute to writer-director Lars von Trier’s gifts as a provocateur. The fact that he spends most of his time in Denmark as a porn producer seems relevant to his exploitation instincts, yet those who have called this blend of Brecht and Our Town anti-American may be overrating its ideological coherence. As in Breaking the Waves and Dancer in the Dark, the heroine suffers greatly, but whether she suffers at the hands of humanity or von Trier himself isn’t entirely clear. With Harriet Andersson, Lauren Bacall, James Caan, Patricia Clarkson, Ben Gazzara, Philip Baker Hall, Udo Kier, and Chloe Sevigny; John Hurt narrates. R. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 4, 2005). — J.R.

This big step forward by comic writer-director Noah Baumbach (Kicking and Screaming, Mr. Jealousy) is a tragicomic autobiographical account of the breakup of his parents’ marriage. The father (Jeff Daniels) and mother (Laura Linney) are both fiction writers living in Brooklyn, and their determination to remain liberated about sexual matters as they separate and divorce drives their two sons (Jesse Eisenberg and Owen Kline) nuts. The implied critique of progressive, bohemian parenting is devastating — wise and nuanced, with the painful hilarity of truth. With William Baldwin and Anna Paquin. R, 88 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the July 18, 1995 Chicago Reader. A perfect illustration of how cheerfully enslaved the New York Times was to Harvey Weinstein’s cultural power and hype. — J.R.

From noted still photographer-turned-director Larry Clark and young screenwriter Harmony Korine, both making their screen debuts, a slightly better than average youth exploitation film (and grim cautionary fable about both AIDS and macho teenage cruelty) that hysterical American puritanism contrived to convert into big news. (The New York Times‘ Janet Maslin called this a wake-up call to the world — meaning, I suppose, that rice paddy workers everywhere, or at least those with phones, should shell out for tickets and stop evading the problems of white Manhattan teenagers.) But if the news is so big, why does it sound like such tired and familiar stuff? And reviewers such as Manohla Dargis who claimed that this depressing movie takes no moral position about what it’s depicting must have been experiencing some form of self-induced shock, because taking moral positions is just about all it does. The photography is striking and the acting and dialogue seem reasonably authentic, if one factors in all the sensationalism, but let’s get real — this was at best the 15th most interesting movie I saw at the 1995 Cannes festival. Read more

Program notes for this double feature at Manhattan’s Public Theater, March 8-13, 1983. A few of the arguments here, such as the comparison of Driver with Straub, strike me now as forced, but when I recall that students in the Downtown Whitney program during the same period compared You Are Not I abusively to The Twilight Zone (and were equally reluctant to regard John Ford as a serious artist when Straub praised him), I think my polemics were warranted….A happy postscript: both films are now available in excellent digital restorations (see below). -– J.R.

Slow yet relentless in their narrative progressions, deliberately nonspecific in their period settings, and equally unimaginable in anything but black and white, YOU ARE NOT I (1981) and THE HONEYMOON KILLERS (1969) are both startling and achieved first films about the triumphs of inexorable wills — each made with a kind of rigor and passion that seem oblivious to the whims of fashion. Small wonder that François Truffaut should be enthusiastic about the earlier film, with its accelerating montage of breathless love letters, its flighty camera movements and implacable bursts of Mahler; or that Jean-Marie Straub should be enthusiastic about the later one (“I liked your film ten times better than Roger Corman’s Edgar Allen Poe movies”), with its integral use of dialectics in conception and treatment alike. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 1, 1988). — J.R.

Clare Peploe’s accomplished and intelligent first feature is a sunny tale of expatriates set on the Greek island of Rhodes, with a cast of characters and a set of crisscrossing destinies that occasionally suggest Graham Greene in one of his happier moods. The people include a talented professional photographer (Jacqueline Bisset) faced with the possibility of having to sell her house, her teenage daughter (Ruby Baker) and ex-husband (James Fox), an art historian who is her oldest friend (Sebastian Shaw), a tradition-minded Greek peasant (Irene Papas) and her rebellious son (Paris Tselios), and an English couple on holiday (Kenneth Branagh and Lesley Manville). Many of these characters are not who they initially seem to be, and there are various forms of comedy in how they relate (or fail to relate) to one another. For spectators who recall Mazursky’s Tempest, this is a much better and smarter handling of many of the same elements, done this time for grown-ups — pleasurable and diverting throughout. (JR)

Read more

Read more

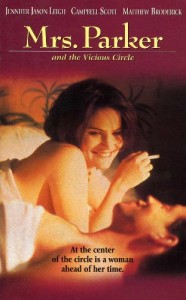

From the December 1, 1994 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Alan Rudolph’s 1994 feature about writer Dorothy Parker and the famous Algonquin wits she hung out with in the 20s certainly has its pleasures, but someone should tell Rudolph that, for all his skill and charm, period movies aren’t really his forte. As a clever postmodernist neoromantic, he’s much better at drawing on the moods of classic Hollywood to reimagine the present than at reinterpreting the past (as he also did in The Moderns, to similar effect). Jennifer Jason Leigh makes an impressive effort to copy Parker’s speech patterns, but her mannerist performance matches the claustrophobic ambience of the direction and script (by Rudolph and Randy Sue Coburn) by conjuring up a profile rather than a life or milieu. At its best this movie manages to be very touching, especially in its handling of Parker’s passionate platonic friendship with Robert Benchley (Campbell Scott); at its worst it shies away so steadily from her leftist politics that you will miss them entirely if you leave before the closing credits. With Matthew Broderick, Andrew McCarthy, Wallace Shawn, Jennifer Beals, Sam Robards, Lili Taylor, and Nick Cassavetes. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 28, 1997). — J.R.

Adapting a beautiful novel by Russell Banks, Atom Egoyan (Exotica) may finally have bitten off a little more than he can chew, but the power and reach of this undertaking are still formidable. At the tragic center of the story are the deaths of many children in a small town when a school bus spins out of control and sinks into a frozen lake (depicted in an extraordinary single shot that calls to mind a Brueghel landscape) and what this threatens to do to the community, especially after a big-city lawyer (a miscast, albeit effective, Ian Holm) turns up and tries to initiate litigation. Egoyan restructures Banks’s novel (which is narrated by several characters in turn and proceeds chronologically) into the kind of mosaic narrative used in his recent features and in most of Kurt Vonnegut Jr.’s novels (in which several different time frames and narrative lines are intercut and proceed simultaneously). He also adds some material about the Pied Piper, capturing the essence of some parts of the book but simplifying most of the characters and making the mountainous setting more mythical. Virtually all of Egoyan’s features revolve around emotional traumas, but this one seems less obsessive — for good and ill. Read more

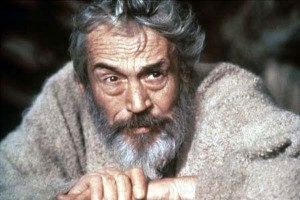

From the December 1, 1992 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

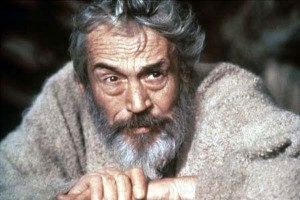

Not nearly as bad as it could have been. John Huston finally wound up as the director of this Dino De Laurentiis blunderbuss (1966), and the overall ambience is much closer to Huston’s high-toned literary adaptations than to Cecil B. De Mille’s biblical epics. Despite the title, the story only makes it through the first 22 chapters of Genesis. The script is credited only to Christopher Fry, but Orson Welles wrote most of the Abraham and Jacob episodes, removing his name from the credits after his ending to the Abraham episode was altered. Probably the best performance is given by Huston himself as Noah, in what is probably also the best segment; other actors include Michael Parks, Ulla Bergryd, Richard Harris, Stephen Boyd, George C. Scott, Ava Gardner, Peter O’Toole, and Franco Nero. 174 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1990). — J.R.

Though crippled by studio recutting that tried to adjust this neurotic 1962 melodrama for the family market, Vincente Minnelli’s adaptation of Irwin Shaw’s novel is one of his last great pictures, reversing the Henry James model of innocent Americans encountering corruption abroad — it’s the Americans who are decadent here. Intelligently scripted by Charles Schnee, the film reunites the director, writer, producer (John Houseman), star (Kirk Douglas), and composer (David Raksin) of The Bad and the Beautiful, describing the attempted comeback of an alcoholic ex-star (Douglas), asked to help a director friend (Edward G. Robinson) with a new picture in Rome, who encounters both his destructive ex-wife (Cyd Charisse) and a redemptive young Italian woman (Daliah Lavi) in the process. George Hamilton plays a spoiled young actor who falls under Douglas’s tutelage, and Claire Trevor plays Robinson’s wife. The costumes, decor, and ‘Scope compositions show Minnelli at his most expressive, and the gaudy intensity — as well as the inside detail about the movie business — makes this compulsively watchable. 107 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

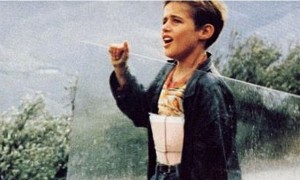

From the Chicago Reader (September 1, 2000). — J. R.

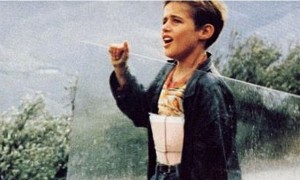

Abbas Kiarostami wrote the story for this charming Iranian suspense picture (1999), reportedly for director Jafar Panahi (The White Balloon), though it was eventually realized quite competently by Mohammad Ali Talebi. A variation on The Wages of Fear, it follows a schoolboy assigned the task of carrying a plate-glass window several miles through a windstorm to his schoolroom to replace one that’s broken. The landscape is beautiful, and the tale itself is pretty mesmerizing. 88 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more