From the Chicago Reader (December 3, 2004). — J.R.

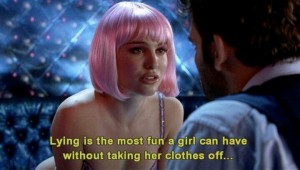

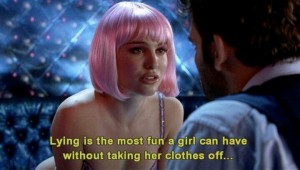

For all his formidable gifts as a performer, Mike Nichols is celebrated mainly as a film director who delivers the goods — which means something only if the goods are worth delivering. Here he’s applied himself to Patrick Marber’s play about two men (Jude Law and Clive Owen) and two women (Julia Roberts and Natalie Portman) seducing, betraying, and punishing one another in various combinations. (The women never get it on, but in the film’s funniest sequence Law flirts with Owen while posing as Roberts in a chat room.) As in Nichols’s previous chamber works of romantic and sexual flagellation (Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Carnal Knowledge), the actors are brilliant, the dialogue extremely clever, and the direction assured. But by the end I couldn’t have cared less about any of the characters (2004). R, 98 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

A program note for the 1997 San Francisco International Film Festival. — J.R.

In this intense drama of courage and humanity in the face of the brutality of slavery, a plantation slave named Nightjohn (Carl Lumblv) defies the law by teaching another slave, a l2-year-old girl named Sammy (Allison Jones), how to read and write. The only other slave on the plantation who even knows the alphabet had a thumb and forefinger chopped off as punishment. Working with a theme akin to that of Ray Bradbury’s novel (and François Truffaut’s film) Fahrenheit 451 — though it’s given a substantially different edge by being set in the past rather than the future — Nightjohn views illiteracy as a central adjunct of slavery. The film isn’t merely a history lesson about people who lived some 165 years ago but a story with immediate relevance. Part of what’s so wonderful about it is its use of fairy-tale feeling to focus on real-life issues, not to evade or obfuscate them. Nightjohn’s ambience is placed at the service of myth — myth that embodies a lucid understanding of both slavery and literacy. Sammy and Nightjohn may sometimes come across as superhuman, but the world they inhabit and seek to change is in no sense fanciful. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1991). Twilight Time’s Blu-Ray of this film has a lot of interesting material about the changes made by Truffaut to Bernard Herrmann’s score. — J.R.

Despite the dedication of this 1967 film to Hitchcock and the use of his most distinguished collaborator, composer Bernard Herrmann, Francois Truffaut’s first Cornell Woolrich adaptation — the second was Mississippi Mermaid — is most memorable for lyrical moods and poetic flights of fancy that don’t seem especially Hitchcockian. Jeanne Moreau stalks gracefully through the film, wooing and dispatching a series of men like an avenging angel whose motivating obsession is spelled out only gradually; among her prey are Claude Rich, Jean-Claude Brialy, Michel Bouquet, Michel Lonsdale, and Charles Denner. Basically an exercice de style, and a good one at that. In French with subtitles. 107 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

This review originally appeared in the March 28, 1997 issue of the Chicago Reader.-— J.R.

The Graduate **

Directed by Mike NicholsWritten by Buck Henry and Calder WillinghamWith Anne Bancroft, Dustin Hoffman, Katherine Ross,William Daniels, MurrayHamilton, Elizabeth Wilson,and Brian Avery.

If I feel myself as the producer of my life, then I am unhappy. So I would rather be a spectator of my life. I would rather change my life this way since I cannot change it in society. So at night I see films that are different from my experiences during the day. Thus there is a strict separation between experience and the cinema. That is the obstacle for our films. For we are people of the 60s, and we do not believe in the opposition between experience and fiction. –- Alexander Kluge, 1988

The Graduate opened in December 1967, the same month the first successful human heart transplant was performed. It was a few weeks after the premiere of Bonnie and Clyde and about three months before the launching of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Among the albums that came out the same year were the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the Rolling Stones’ Their Satanic Majesties Request, and the Mothers of Invention’s Absolutely Free. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1994). — J.R.

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger transfer the plot of Johann Strauss’s opera Die Fledermaus to postwar Vienna for a 1955 musical filmed in Technicolor and ‘Scope. Not one of their best movies (cf The Red Shoes and A Matter of Life and Death), but it’s certainly an engaging mannerist oddity that calls to mind such contemporary cross-references in delirium as Frank Tashlin and Vincente Minnelli, and the cast — Anton Walbrook, Michael Redgrave, Anthony Quayle, Mel Ferrer, Dennis Price, and Ludmilla Tcherina — is occasionally as enterprising as the candy-box decor. (JR)

Read more

Read more

This appeared in the June 18, 2004 issue of the Chicago Reader. —J.R.

Bitter Victory

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Nicholas Ray

Written by Rene Hardy, Ray, and Gavin Lambert

With Richard Burton, Curt Jurgens, Ruth Roman, Raymond Pellegrin, Anthony Bushell, Andrew Crawford, Nigel Green, and Christopher Lee.

Jane Brand: What can I say to him?

Captain James Leith: Tell him all the things that women have always said to the men before they go to the wars. Tell him he’s a hero. Tell him he’s a good man. Tell him you’ll be waiting for him when he comes back. Tell him he’ll be making history. —Bitter Victory

This week, as part of its series devoted to war films, the Gene Siskel Film Center is showing a restored version of Nicholas Ray’s little-known masterpiece Bitter Victory—a powerful, albeit flawed, black-and-white CinemaScope feature set mainly in Libya during World War II. This 1957 film offers a radical reflection on war, and its relevance to the current war in Iraq goes beyond the desert settings and references to antiquity.

Many films are regarded as antiwar, including ones that proceed from antithetical premises; in the 60s a popular revival house in Manhattan liked to run a double bill of Grand Illusion and Paths of Glory. Read more

From the January 1, 1995 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

In the first of his independent features as producer-director (1953) Otto Preminger adapts his most successful stage production, a light romantic comedy by F. Hugh Herbert that ran for over 900 performances. Released without production code approval and condemned by the Legion of Decency for its use of such taboo phrases as virgin, seduce, and pregnant, none of which bothered anyone in the stage run, it’s regarded today mainly as a curio. Yet for all the movie’s staginess and datedness, it’s a more personal and ambiguous work than it initially appears to be. Architect William Holden ogles and picks up professional virgin Maggie McNamara at the Empire State Building and brings her back to his apartment, where his next-door neighbors — his former girlfriend (Dawn Addams) and her playboy father (David Niven) — quickly involve this potential couple in various intrigues. A certain prurient (as well as analytical) curiosity in Preminger’s distanced and mobile camera style makes McNamara seem slightly corrupt and Holden and Niven slightly innocent, despite all appearances to the contrary, and the sour aftertaste to this frothy material is an important part of what keeps the picture interesting. Read more

From the October 1, 1996 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

I don’t know anything about the novel this Nicolas Roeg made-for-BBC film is drawn from — Stephen Dobyns’s The Two Deaths of Senora Puccini, adapted by Roeg’s longtime collaborator Allan Scott — but its mixture of metaphysical fireside tale and kinky guilt tripping reminds me of Graham Greene’s Doctor Fischer of Geneva. During a bloody 1989 student uprising in an unnamed country that seems to be somewhere in eastern Europe, a successful doctor (Michael Gambon) is holding his annual dinner for three of his former schoolmates and recounting in flashbacks the story of his sexual obsession with a schoolteacher (Sonia Braga) who despises him but now lives with him as his slave. As his three male guests relate their own sexual secrets and soldiers and police periodically break into the house, the pattern of an after-dinner parable laced with vague allegorical undertones gradually takes shape. The results are engaging (if unpleasant) as story-telling — and alternately striking and pretentious as only a Roeg film can be. With Patrick Malahide, Ion Caramitru, Nickolas Grace, and John Shrapnel. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 20, 1999). — J.R.

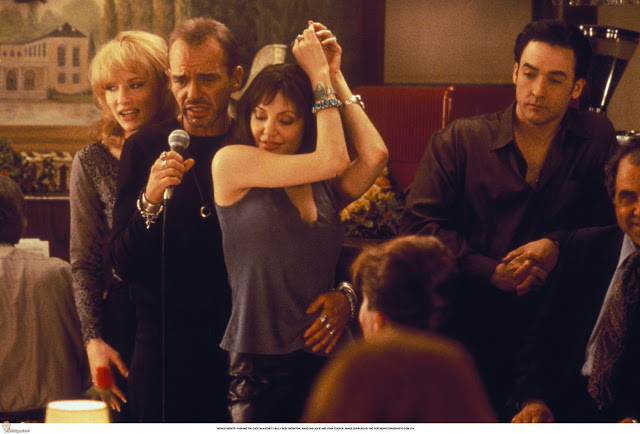

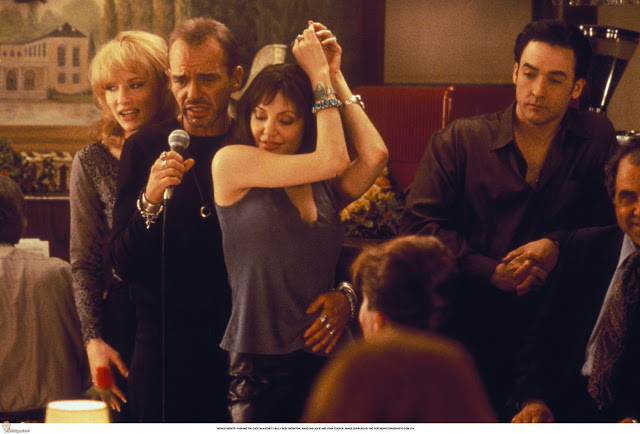

Though this comedy-drama about a macho feud between two New York air-traffic controllers (John Cusack and Billy Bob Thornton) is never entirely believable, it’s consistently lively, offbeat, and unpredictable, suggesting at times the improbable fusion of Howard Hawks and Sigmund Freud. Inspired by an article by Darcy Frey in the New York Times Magazine, the screenplay by brothers Glen and Les Charles (creators of the TV show Cheers) piles hyperbole on top of frenzy in spelling out the heroes’ frenetic lifestyle. In particular, it focuses on the putative wife swapping (involving Cate Blanchett and Angelina Jolie) that emerges from the rivalry. Cusack may be called upon to hog too much of the limelight, if only because the story is mainly told from his point of view, but director Mike Newell’s flair for mixing and matching his entire cast seldom falters. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1994). — J.R.

A first feature by American independent writer-director David O. Russell, this traps its hero, a premed college freshman, in his family’s suburban home for the summer. Forced to give up an internship to take care of mother (laid up with a broken leg) while his philandering father, a traveling video salesman, is out on the road, the not very likable hero finds himself in one tragicomic mishap after another involving his father’s convoluted instructions, care of the family dog, making out with a high school senior, and a growing sexual involvement with his desperate mother. Despite a certain originality, the movie isn’t really a success, not only because the plot bites off more than it can chew (the film doesn’t conclude; it simply stops), but also because, like its hero, it has some trouble distinguishing between petty irritations and cataclysmic traumas. But at least the performances are fresh and fairly nuanced. With Jeremy Davies, Elizabeth Newitt, Benjamin Hendrikson, Alberta Watson, Carla Gallo, and Richard Husson (1994). (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the August 15, 2003 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

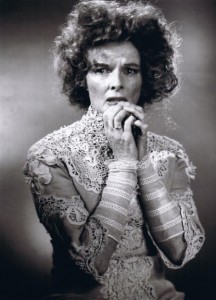

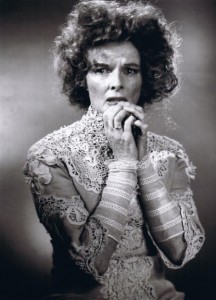

Eugene O’Neill’s greatest play — written in 1940, but published only posthumously, in 1956 — is a frankly autobiographical look at his own doomed family, set in 1912, when he was in his early 20s. Sidney Lumet rightly retained the entire text for this 1962 black-and-white feature, which runs for 174 minutes. It’s as close to a definitive version as we’re likely to get, and it includes what is probably Katharine Hepburn’s greatest noncomic performance. The other three actors — Ralph Richardson as the father, Jason Robards Jr. as the older son, and Dean Stockwell as the younger son (O’Neill’s self-portrait) — keep pace with her every step of the way. (JR)

Read more

Read more

Written for the catalogue of Il Cinema Ritrovato, June 24 through July 4, 2015. — J.R.

THE MAN FROM LARAMIE

USA, 1955

T. it.: L’ Uomo di Laramie. Sog.; Thomas T. Flynn. Scen.: Philip Yordan, Frank Burt. F. (CinemaScope): Charles Lang. M.: William Lyon. Mus.: George Duning, Lester Lee. Int.: James Stewart (Will Lockhart), Arthur Kennedy (Vic Hansbro), Donald Crisp (Alec Waggoman), Cathy O’Donnell (Barbara Waggoman), Alex Nicol (Dave Waggoman), Aline MacMahon (Kate Canady)., Wallace Ford. Prod.: William Goetz Productions.

“Anthony Mann brought a touch of Oedipus Rex to almost everything he did—he was fascinated by families exploding from the inside—but in this 1955 western it’s more than a touch: he’s clearly aiming for classical resonance. Yet the film is never pretentious, perhaps because Mann is able to create characters complex enough to support the grand emotions, and because the landscape—animistic, enveloping—becomes mythic in his wide-screen framing. It’s one of Mann’s cleanest, clearest films, constructing an elaborate but ultimately lucid network of character relationships, all of them perverse. With James Stewart, Arthur Kennedy, and Donald Crisp. 104 min.” (Dave Kehr in the Chicago Reader)

This is the eight and last of Anthony Mann’s features starring James Stewart, made over a mere six years (1950-1955)—a fascinating body of work that, like Alfred Hitchcock’s uses of Stewart over roughly the same period (in Rope, Rear Window, and Vertigo) as well Cecil B. Read more

The following was commissioned by and written for Asia’s 100 Films, a volume edited for the 20th Busan International Film Festival (1-10 October 2015). — J.R.

A Brighter Summer Day was inspired by a true incident, a touchstone from Yang’s youth: the killing of a 14-year-old girl by a male high school student in Taipei on June 15, 1961. Yang frames the film with recitations over the radio of the names of students graduating from the same school in 1960 and ’61. The title comes from the lyrics of the Elvis Presley song “Are You Lonesome Tonight?”, phonetically transcribed by the hero’s sister so that a younger friend, Cat, can learn to sing them.

This song is only one of many cherished artifacts belonging to the film’s characters that come from somewhere else. A samurai sword found by the hero, Si’r, in his family’s Japanese house becomes the murder weapon, and a tape recorder left by the American army in the 50s records Cat’s version of the Elvis song. An old radio that for most of the picture doesn’t work eventually broadcasts the list of graduating students. And a flashlight Si’r steals in the first extended scene from a film studio next to the school, where he periodically hides in the rafters to watch movies being shot, makes a fascinating progress through the film. Read more

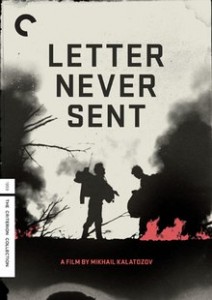

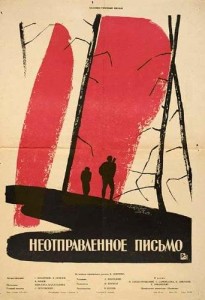

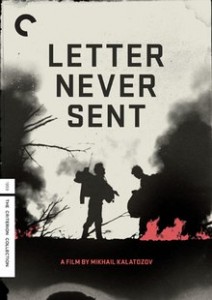

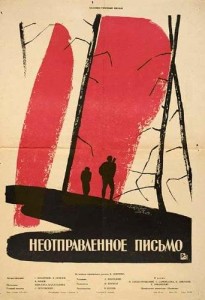

From the Chicago Reader (August 1, 2001). — J.R.

Two years after his internationally famous The Cranes Are Flying and five years before his internationally scorned I Am Cuba, Mikhail Kalatozov directed this strange 1959 adventure story about four geologists (three men and one woman) hunting for diamonds in Siberia. The title letter is being written by the narrator to his wife in Moscow, and while the explorers eventually find their treasure, they have to endure forest fires and snowstorms as they struggle back toward civilization. Though shot on location and reportedly based on a true story, the film is distanced considerably from realism, at least in any conventional sense, by its exciting and volatile camera style and its metaphysical atmosphere (sparked in particular by one line of dialogue, Nature is taking revenge); they’re less delirious than in I Am Cuba but sufficiently ravishing to have brought charges of formalism against the filmmakers. Pictorially, the double exposures and silhouette effects recall some of the glories of silent cinema. in Russian with subtitles. 98 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

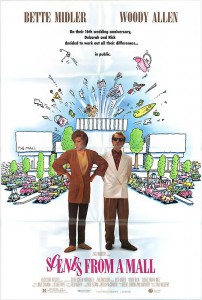

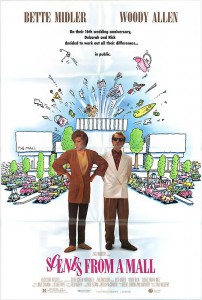

From the Chicago Reader (February 1, 1991). — J.R.

A middle-aged couple (Woody Allen and Bette Midler) in southern California celebrating their 15th anniversary go to a shopping mall, and they proceed to decompose and recompose their relationship on the basis of various revelations. Although this only runs for about 90 minutes, it’s the emptiest and most long-winded movie Paul Mazursky (working here with his frequent cowriter Roger L. Simon) has ever made, a disappointingly steep descent after his Enemies, a Love Story. The characters never come to life, and restricting almost all of the action to a gigantic mall only makes the narrowness and boredom of the movie more obvious. Mazursky has returned with a vengeance to his special universe where the upper middle class is the only thing that exists, and this time he has absolutely nothing to say about it. (JR)

Read more

Read more