From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1988). — J.R.

On the evidence of Elia Kazan’s recent autobiography, it is this low-budget, independent feature of 1972, shot in super-16-millimeter, that comprises his true last (or at least last personal) film, rather than The Last Tycoon, which he embarked on mainly for the money four years later. Scripted by Kazan’s son Chris and shot in and around their Connecticut homes, the film offers some disturbing yet relevant echoes of themes in other Kazan pictures: the pacifist who finds himself driven to violence and the hatred-provoked hero who squeals on his buddies (reflecting Kazan’s naming of names to the HUAC in the early 50s). Two Vietnam vets released from Leavenworth after serving time for the rape and murder of a Vietnamese woman go to visit the former buddy who turned them in, who is now living with his girlfriend and their young son in the home of her father, a macho, alcoholic novelist. There’s a lot of prolonged waiting around while the two convicts circle their prey and prepare their revenge. While Kazan makes the most of the ambiguous personalities involved — he is especially good with his James Dean-ish discovery Steve Railsback, as well as with an early James Woods performance — the abrasive sexism of the overall conception, which recalls Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs in spots, makes this the most unpleasant of all his films. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1988). — J.R.

This 1983 Steve Martin vehicle may be a little slapdash here and there as filmmaking, but it probably has more laughs than any other Martin comedy (with the possible exception of The Jerk). Martin plays a brain surgeon who contrives to resurrect his bitchy, beautiful late wife (Kathleen Turner) with the transplanted brain of a gentler soul. Far from avoiding the tackier implications of this concept, the film revels in them like a puppy in clover; Martin’s delivery of the line, “Into the mud, scum queen!” is alone nearly worth the price of admission. With David Warner; directed by Carl Reiner. (JR)

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1988). — J.R.

Oddly enough, Jean Renoir’s 1946 Hollywood version of Octave Mirbeau’s novel was a lot crueler and more “Buñuel-esque” than this, Buñuel’s own remarkable and neglected 1964 French version. It was the first of his many fruitful collaborations with screenwriter Jean-Claude Carriere and producer Serge Silberman, and, if I’m not mistaken, his only encounter with ‘Scope (in black and white). Formally and thematically, this is one of Buñuel’s subtlest and most intriguing late works; the novel’s action is updated to the 30s and includes a commentary on the French fascism of the period. Jeanne Moreau plays the heroine, and others in the cast include Michel Piccoli, Georges Geret, and Francoise Lugagne. The absence of a musical score makes Buñuel’s use of sound especially beguiling. In French with subtitles. 101 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 1, 1988). — J.R.

The tenth and latest feature of European avant-garde filmmakers Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet — filmed in Sicily and using as its text the first of three versions of Friedrich Holderlin’s unfinished 1798 verse tragedy — is one of their most beautiful works; but like all the best avant-garde work, watching and listening to it requires some adjustments in our usual activity as spectators — adjustments that involve new areas of play as well as work. This is a film in which sound matters at least as much as image, and where the lovely natural settings (filmed in 35-millimeter by Renato Berta) are as important as the actors and the text. The sound of Holderlin’s highly metered German blank verse is the most sensually rich use of that language that I have ever heard, and even if, like me, you don’t understand the language, the selective subtitles should be regarded as footnotes to glance at rather than as a substitute for the main text. Unlike the texts in Straub and Huillet’s early work, the text here is dramatically and expressively acted, and the compelling cast includes Andreas von Rauch as Empedocles (a Greek philosopher expelled from his community for blasphemy, and bent on suicide), Howard Vernon (who acted in Fritz Lang’s The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 1, 1990). — J.R.

Alfred Uhry adapts his own play about the relationship between a crotchety, elderly Jewish woman living in Atlanta (Jessica Tandy) and the slightly younger black man (Morgan Freeman) hired by her businessman son (Dan Aykroyd) to drive her around (1990, 99 min.). Uhry’s play, which won a Pulitzer Prize, is a sentimental actors’ vehicle so fundamentally theatrical in conception that nothing can really make it into a film; aided by a lachrymose Hans Zimmer score, it fairly drips with the kind of nostalgic liberal platitudes that make its upscale target audience applaud at the end — they’re actually applauding themselves. Fortunately, the three actors manage to get a lot of mileage out of the material: although one never quite believes that Tandy’s character is Jewish, she is remarkable in every other respect, and Freeman and Aykroyd are wonderful throughout. The movie also has something legitimate and instructive to say about the subtlety and intricacy of everyday race relations in the South during the period covered (roughly 1948 to ’73). The self-conscious period decor by Bruno Rubeo is never quite convincing — Atlanta is never made to seem like a large city — and the mise en scene of director Bruce Beresford basically consists of letting the actors do their utmost. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 1, 1988.) — J.R.

A William Wellman curiosity done for Warners in 1931, this gritty thriller, a favorite of film critic Manny Farber, is of principal interest today for its juicy early performances by Barbara Stanwyck, Joan Blondell, and Clark Gable. Hard as nails, with lots of spunk. 72 min. (JR)

Read more

From the October 1, 1989 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

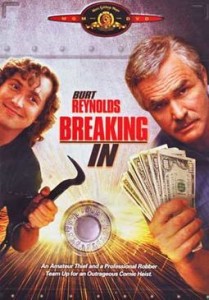

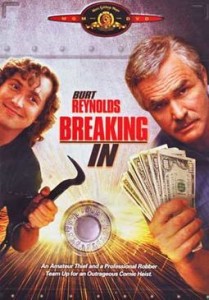

An aging burglar (Burt Reynolds) takes on and trains a younger partner (Casey Siemaszko) in a quirky and likable 1989 comedy directed by Bill Forsyth and scripted by John Sayles. This film lacks the ambition of Forsyth’s earlier Housekeeping, but it’s warm, engaging, and very agreeably acted (Reynolds hadn’t been this good in ages); most of the focus is on the warmth that develops between the old pro and his student in crimea little bit like the rapport between older and younger men found in some of the movies of Howard Hawksand Sayles’s refreshingly nonjudgmental script has plenty of small-scale pleasures of its own. With Sheila Kelley, Lorraine Toussaint, and Albert Salmi. (JR)

Read more

Read more